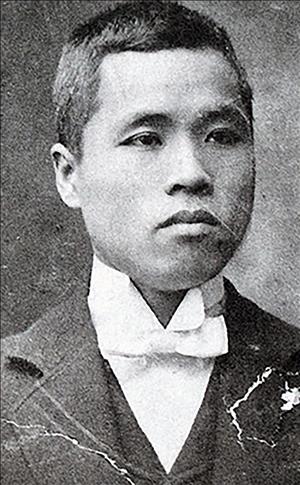

On October 22, 1902, the Washington State Supreme Court denies citizenship for University of Washington School of Law graduate Takuji Yamashita (1874-1959). At this time, only U.S. citizens are admitted to the bar, a requirement for practicing law in Washington state. An 1882 federal law limits U.S. citizenship "to aliens being free white persons and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent." This law is not changed until 1952, too late for Yamashita.

A Gifted Young Man

Yamashita immigrated to Tacoma from Japan and waited tables at Nishii's restaurant during the 1890s. He lived at the Tacoma Baptist Mission and graduated from Tacoma High School in just two years.

The University of Washington opened its law school in 1899 in downtown Seattle, near the courts and law offices of its instructors. Any qualified man or woman with the $25 annual tuition could be admitted. Yamashita moved to what is now Seattle's International District in 1900 and enrolled in the challenging two-year program. In his essay, "A Civil Action," Steven Goldsmith writes, "Yamashita's contribution, especially in the moot court, was described in a year-end school wrap-up as 'commendable.'" Yamashita passed the oral bar exam in Olympia, but he still had to qualify for citizenship, granted at that time through the state court system.

Injustice By Law

Washington Attorney General Wickliffe B. Stratton (d. 1936) held that Yamashita could not become a citizen because "in no classification of the human race is a native of Japan treated as belonging to any branch of the white or whitish race." Yamashita took his own case to court and filed a 28-page brief. On October 22, 1902, the Supreme Court decided against the immigrant and cited precedents in which other Asians had been denied citizenship because of their race.

Yamashita opened restaurants along the waterfront in Seattle, but the Washington Constitution barred Asians from ever owning their farms or the real estate under their businesses. Yamashita and Charles Kono countered by forming a corporation to own property. When the Washington Secretary of State refused their application, the two immigrants went to court. That case and one from Hawaii went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. The cases, which the immigrants lost, used some of Yamashita's original arguments from 1902.

In His Late 50s: Internment

Yamashita went into the hotel business in Bremerton and in Silverdale. During World War II, the United States government interned him and his family along with 110,000 other Japanese Americans and he lost his businesses.

After the war, he worked as a live-in housekeeper in West Seattle. In 1957, he and his wife moved back to his hometown in Japan. Takuji Yamashita died there in 1959.

In 1952, Congress changed the law to allow Japanese persons to become U.S. citizens. Nearly 50 years later, the UW School of Law, the Washington State Bar Association, and the Asian Bar Association of Washington successfully petitioned the state Supreme Court to admit Yamashita posthumously as an honorary member of the State Bar. Hundreds of people witnessed the court's action, conducted in a public ceremony on March 1, 2001.

In July 2001, 23 of Yamashita's grandchildren and great-grandchildren, mostly in Japan, endowed a scholarship to support UW law students interested in international law and human rights. The Asian Bar Association of Washington has also dedicated a scholarship in Yamashita's name.