Walt Sickler (b. 1927) worked for Seattle City Light for 40 years. In 1989, he retired as the Director of Operations, in charge of all the dams, power transmission systems, and shops. His first job was on a line crew and in this interview conducted by HistoryLink's David Wilma, he recalls those years.

The Interview

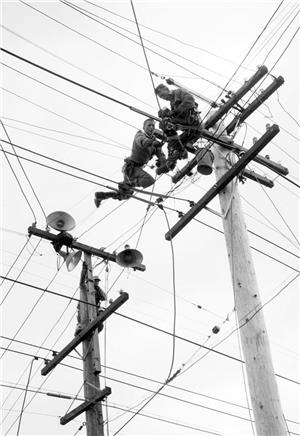

"As a youngster, my father was a lineman and I idolized him as a lineman and my desire was always to be a lineman. My father was killed in 1939 in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in an electrical accident on a pole. My grandfather was a lineman in Des Moines, Iowa, and he was killed when my father was 12 years old. He fell off of a pole. And subsequently we moved to Washington.

"I went into the Navy in 1943 and was an electrician in [the Navy] and when I got out of the Navy I applied for it. Took an examination for Lineman Helper at Seattle City Light and I was hired in June of 1949. I took the test in 1948 and at that time they had two registers, resident and non-resident and I lived outside the city, so it wasn't until 1949 when I got down on the list and subsequently I moved into the city to keep my job.

Helper

"My first job was as an electrical helper in the yard shaving poles. At that time we hand-shaved the poles with a draw knife and prepared them by putting creosote on the butts of them. I was just there a short time because it was my desire to be on a line crew. I went from there to a pole setting crew, that was the next step. And then as a helper on the line crew.

"A lineman helper was the extension of the lineman on the pole, he of course had to have material sent up to him and things done for him. So the helper went and got material from the truck and made up the material and sent it up to the lineman. The saying of the linemen used to be, "I don't care how high the helper climbs as long as he keeps one foot on the ground." For helper there was no training for it other than you took a regular physical examination, you had to pull a rope through a pulley for one minute and then you had physical lifting and such. Then when you took a test for lineman, it was a written and a working test, you had to show an ability to climb pole and hang crossarms and do various things. And also pass a written test on safety rules and company construction policy.

"During the lunch hour, helpers would borrow a lineman's climbers and go out. I used to be in White Center and I used climb a pole and we used to have a telephone handset and I'd climb up to the telephone arm and call people just for practice. And then on a wet day, if a lineman came down the pole and cleared up and weren't going to work any more, they'd allow the helpers to up the pole and clear up the stuff and send it down. And eventually they called you a climbing helper and you got to work with a lineman, and if a lineman was off, they'd upgrade you to a lineman for the day. When I went to work for City Light as a helper, it was $1.05 an hour. A lineman was getting a little over $2.00 an hour. And then we got a big boost in 1951 when City Light took over Puget Power. We had to climb through their voltage to get to our stuff, so they gave us 50 cents a day more.

Lineman

"The work of a lineman was a very hazardous trade, as evidenced by both my father and my grandfather killed. We had more than our share of fatal accidents at City Light and so it was very tense. At the end of a work day they were just like a bunch of kids. We used to have water bags on the front of the truck. That's what we drank water out of. The water fights were something else. It was just a way of letting off tension, because you were through for the day. I know when I was a line crew foreman, sometimes I wanted to curb the guys because sometimes they could get out of hand because you're out in the public like that. I just attributed it to the fact that because of the high tension of the job, that it was time to relax.

"And then in the '60s when we got the apprentices, they became the scapegoats for everything. The linemen used to refer to them as lower than helpers and [it was] almost a charge to make them qualified to do the job. They went through an initiation program to be part of the crew. Nail their lunch pail to the inside of the truck. Not let them in the truck. Make them ride in back with the helpers. And of course the linemen had complete authority over the apprentices and the helpers. It was like the captain of a ship. You didn't talk back to the linemen.

Line Crews

"We had two size crews. In the 50s we had a cutting crew and that was two linemen and a foreman and two helpers and a driver. They hung transformers and ran services. And then the larger crews that I was part of all my career was heavy line trucks. They had six linemen, six helpers, a pickup driver, a truck driver, and a foreman. Quite a massive crew in one pile in a city street. In the early '50s we were hooking up the unit substations. That's where you converted the 26 KV [kilovolt, 1,000 volts] down to 4 KV distribution. And the intent at that time, you had to have one every square mile in the city. So we had heavy crews running the primary voltage, the 4 KV and then the 26 KV, hooking up these substations. It was a tremendous amount of work.

[In 1951, Seattle City Light acquired the properties of competing private utility, Puget Sound Power & Light] "When they fired Puget Power, their facilities were in pretty rough shape and of course we had to cut theirs all over to ours and strip out theirs.

"We used to leave the barn and go out to the job. You'd dress up. You'd get your "carharts" on and your climbers. Carharts is a pair of canvas overhaul, they're a reddish-brown. It was sort of the trademark of a lineman to protect his clothes. The foreman would look around if it was a new job to see where he was going to begin the task. And he'd assign the linemen. Each lineman had a helper. A helper was called a "grunt." And the lineman told the grunt I want such and such a thing on a handline and off they would go to their assigned job.

"At lunchtime, it was a tradition, they would go to a substation that had room in it. Mostly they went to fire stations so they could dry out and they had an hour lunch. Then they could return to the job. Mostly they went to a place where they could get in out of the weather to eat.

City Light acquires Puget Power

"When I first went to work there, they only had one service center and that was at 4th and Spokane. My first job as a helper, we went clear out to NE 145th and 5th NE to set poles for a substation. I thought we'd gone to the end of the world because it was so far north. Then in the '50s when we took over Puget Power, then they established quarters at 8th and Roy. And that's where the Puget crews worked out of until we integrated. They [the Puget Power crews] stayed pretty much single for awhile. As I recall they sent one or two crews out there sort of as a liaison to get the Puget crews adapted to being involved in City Light.

"You have to appreciate there was strict competition between the two companies for many, many years. I don't know that it got down to the line level. Used to have two services to a house. We were constantly going out and cutting out one service and cutting in the other. People would get mad at Puget Power and want City Light. I think in the later '40s, early '50s, they stopped that practice.

"It [working around Puget Power lines] was difficult, because your secondary to your service wires to the houses, if it was a joint pole, where you had telephone, Puget Power, and City Light, City Light always occupied the top gains on the pole and Puget Power was in the middle. You had to go through their primaries. Of course our servicing going to houses were just above the Puget primaries. State law requires a certain distance between them, but it isn't all that sufficient and it was easy to get very close to that primary and it was necessary to put rubber goods [insulating covers] on them to make sure you didn't get electrocuted. It was an interesting thing because we did that for years prior to the takeover, but then after the takeover, we got 50 cents a day for going through the primaries. I guess because then they were ours. We never touched their wires and they never touched ours. That was a no-no.

"It was a very smooth integration, partly due to a little Irishman, general foreman, general supervisor, Jerry Dermody. He insisted that the Puget crews be treated as part of City Light.

Accidents

"I honestly don't recall any accidents that were actually the results of people getting the PS primaries. I can remember getting rapped a few times, because of getting too close to it. Maybe the [rubber] goods slipped off and your foot has slipped down too close to the primary and, of course if you made direct contact it would be fatal, but close enough that you could get shocked. Electricity doesn't jump like a lot of people think. There's leakage from the insulators down. It was not an easy task, and we were very happy to get those Puget primaries out of the way.

"We had such a heavy load density, that means the wires were carrying such terrific loads that the fault current, that means when you break a wire apart, there's a tremendous arc from it. The load density means we were running those primary wires, six wires on a crossarm and it was really close proximity and due to human nature, I guess, people just got careless at times. I can recall back that several of our fatal accidents were just the fact that the person didn't rubber up properly or think what they were doing. You have to think that if you're under that tension for all the hours a day a lineman is, it's easy to have a slip-up. My crew only had a fellow shocked severely and falling off a pole. The only severe accident I had as a foreman was I had one lineman fall off a pole and he was broken up pretty bad. No fatalities.

"It seemed in the '50s, as I recall back, that there was just about one fatality a year. If the Fire Department or the Police Department has somebody fall in the line of duty, they used to have quite a to do about it, because they were public service. But we always thought linemen were public service too. But for our own, we grieved them. It was a sobering thing, especially for me because having lost my father as a boy I knew what it was to lose a breadwinner out of a family. Safety had to be the most important part of our job.

"I became a line crew foreman in 1960. I was a line crew foreman until 1973 and then I was appointed to Overhead Systems Supervisor. I had a large crew. I did a lot of the heavy transmission work for the city. In the early '70s they had to run more transmission lines into the south end of Seattle and we had two transmission lines that would carry four circuits on the old lattice towers. Our right-of-way was limited and we needed six transmission lines to go into there so I had the job of taking the wire out and we had a contractor put steel poles in with arched arms out. They could get three circuits, three tower lines in the same right-of-way that the two used to be on. We went in and restrung the transmission lines in. We had six linemen and six helpers.

Old-timers

"Longevity was a matter of pride [at City Light]. You didn't change much. It was colorful. About everybody, especially the line crew foremen, had nicknames. Some can be repeated, some can't. The old-timers were proud just like when we did it, we had to climb poles. Young guys now have all the aerial man-lifts. Some of the old-timers relayed back to us some of the difficulties that they endured.

"They didn't have the heated trucks that we had. The back of the truck just had a canvas top on it and they had to sit in the back and go between jobs. They had what they called a "blow-pot." That's what they used to heat lead, the solder to solder dead-ends that we made. They would have to sit in the back of the truck with this blow-pot to keep warm. And the other thing that they had was called a fire-can. We don't have those now. We used to have a barrel that they would throw pieces of crossarm and wood pins in it. It would heat up and keep warm on the job. And then they would hook it on to the back of a truck while they were going from job to job. There were all sorts of horror stories of what happened when these buckets would fall off. I recall one of the crews that said it fell off down at the corner of Yesler Way and 2nd Ave. That was quite a ruckus.

"It was kind of hazardous especially if it got really cold. They'd try to keep the tarps all the way down. The pots back there, they were a high pressure gas or kerosene that they had to pump up. The fumes would be pretty sever and they would come out of there half grogged."

Walt Sickler was promoted to management in 1973. He went on to be Manager of Overhead Construction and in 1978, he was appointed by Superintendent Gordon Vickery to be Director of Operations.