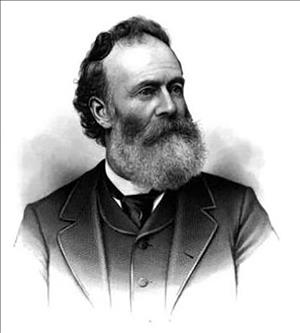

Henry A. Smith, M.D. was a Seattle physician who developed property on the west slope of the neighborhood of Queen Anne, part of which bears the name Smith Cove. Named after him as well are Smith Street in Seattle and Smith Island in Snohomish County. He is remembered as a local poet and transcriber of Chief Seattle's famous 1854 speech to the Territorial Governor. He served for a time as Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He set out the first grafted orchard in King County, and became the county's first superintendent of schools. He also served as physician at the Tulalip Reservation in Snohomish County.

One of Nine Children

Born near Wooster, Ohio, Henry Smith was descended from English (maternal) and German (paternal) pioneer stock. His father's grandfather, Copleton Smith, served in the Revolutionary War and once owned a large piece of today's downtown Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Smith's father, Rev. Nicholas Smith, served in the War of 1812, married Abigail Teaff of Virginia, and then moved to the Ohio frontier. They produced nine children.

Educated in Ohio public schools, Henry Smith was introduced to medicine at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania. Just as lawyers in those days trained as apprentices to experienced lawyers, Smith learned the practice of medicine as assistant to and pupil of Dr. Charles Roode in Cincinnati, Ohio. After his medical training, he practiced for a time in Keokuk, Iowa.

Going West

In the early 1850s, like many of his countrymen and women, he was attracted to the West. In 1852, he crossed the plains in a large wagon train en route to the fabled riches of California. Smith also looked after two special passengers: his mother and sister. With his medicine bag and nostrums at hand he relieved the suffering of traveling companions, many with cholera.

After six months of arduous travel, the bulk of his party reached the 100-person logging village of Portland, Oregon. At that time -- late 1852 -- Isaac I. Stevens (1818-1862), the newly appointed Washington Territorial Governor, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, and railroad engineer, was surveying a road to Puget Sound country. Smith was attracted to the northern route and to the dream of an anticipated railroad. He proceeded up the Cowlitz River, boarded a ship at Olympia, and stepped ashore near the tiny hamlet of Seattle on Elliott Bay.

Despite the fact that Dr. Smith found another physician in Seattle, David "Doc" Maynard (1808-1873), there was plenty of room and Smith took a claim of 160 acres on a bay north of town -- soon known as Smith's Cove. Once settled, Smith sent for his mother and sister who were awaiting word in Portland, Oregon.

According to Roberta Frye Watt, in Four Wagons West, Smith hoped that the inevitable rail line to Puget Sound would terminate at or near his holdings. In fact, Smith, as a member of the territorial legislature, joined an effort to petition Congress regarding the need to connect Eastern Washington with Puget Sound. Congress accepted the idea, but the American Civil War interrupted all road-building and other projects for the duration of the conflict.

Smith's neighbors were members of the local Duwamish and Suquamish Indian nations, a few white families on Donation Land Claims huddled in today's downtown Seattle, and workers at the sawmill of Henry Yesler (1810-1892). His rival, "Doc" Maynard, spent a fair amount of his time dabbling in real estate and local politics, so Smith developed a good medical practice without much trouble. To supplement his income -- and while waiting for patients -- he engaged in farming, planting potatoes, and grafting fruit trees. By 1853, Smith had erected his first log cabin. In 1854, in a larger log building, he established an infirmary.

Going in Circles

A favorite Henry Smith story is one he often told on himself. While clearing land at Smith's Cove he started to blaze a trail to the nearby village of Seattle. After working his way through a thick Douglas fir, hemlock and cedar forest, he came to a clearing which he assumed was a neighbor's claim.

He sat down to rest and noticed how similar the clearing was to his own property. A rooster looked familiar; so did a woman wearing a blue dress who was feeding chickens. Suddenly it dawned on him: he had blazed a circular trail and had returned to his own property. That was his rooster and the woman dressed in blue was his mother.

Battle of Seattle

Indian troubles of the 1850s, including the January 26, 1856 Battle of Seattle, caused Henry Smith to take a role in the local militia. Sophie Frye Bass, in Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle, notes that Smith at one time took his mother and sister to the safe and secure blockhouse on Cherry Street. When he returned to his Smith's Cove property, he found that his cabin and barn had burned to the ground.

By the mid-1850s, Smith was farming, nurturing fruit orchards, and investing in real estate. One of his land deals was at the mouth of the Snohomish River, later called Smith Island. This area consisted of unprotected tide flats and was therefore subject to seasonal flooding. Despite building dikes in an effort to replicate the Holland experiment, waters drowned his fruit orchards. While struggling to tame the land, he wrote poetry and described his pioneering agricultural experiences in local newspapers.

In 1862, Smith married Mary A. Phelan (d. 1880), a native of Wisconsin. The Smiths produced seven daughters and one son.

House Calls By Canoe

During the Snohomish years, Smith's medical practice extended throughout a five-county area. Most of his house calls were made by Indian canoe. After six years, he was appointed government physician for the Tulalip Indian reservation. Apparently there was no end to Dr. Smith's interests during this period, as he found time and energy to own and manage a number of logging camps and a general store.

While farming and practicing medicine at the mouth of the Snohomish River, his Smith's Cove properties were rising in value. By the late 1870s, he owned almost 1,000 acres at the foot of Queen Anne Hill. Shortly after returning to Seattle to develop his holdings, in 1880, his wife Mary (Phelan) Smith died. Henry Smith was left to raise eight children, aged 1 to 16. They were:

- Lulu (b. 1864; married Richard Pennefather);

- Luma (b. ca. 1866; married George Linder Jr.; d. 1939);

- Maude (b. 1868; married Charles Teaff; d. 1898, not 1908 as erroneously stated in several sources);

- Laurene (d. 1959);

- Ralph Waldo (b. 1872; drowned in Alaska sometime after 1900);

- May (1874-1948);

- Ione (b. 1877; married C. Frederick Graff; d. 1972);

- Lillian (b. 1879; married and divorced William Tompkins; married Alfred Hoke).

One pioneer's memory of Smith recalled that many lonesome, single men discovered they had maladies requiring the doctor's attention. While receiving medical attention, they took advantage of opportunities to meet and court the Smith daughters.

Chief Seattle's Speech

Henry Smith continued to write poetry and reminiscences for local newspapers. Among his writing projects were notes he took of a speech Chief Seattle made to Governor Stevens in 1854. The occasion was the establishment of Indian reservations throughout the Territory of Washington. For the Indians it was a sad moment made more distressing by its inevitability, as Euro-Americans entered the Pacific Northwest in growing numbers. After the governor explained the reason for the 1854 meeting (to sign treaties) Chief Seattle stood up, placed his hand on the governor's head (Chief Seattle was quite tall, and Governor Stevens was unusually short), and delivered his famous oration.

Chief Seattle's speech went unnoted in the written record until October 29, 1887, when the Seattle Sunday Star published a text reconstructed from incomplete notes by Dr. Smith. Smith rendered his memory of the speech in the rather ornate (to modern ears) English of Victorian oratory. Chief Seattle would have given the speech in the Lushootseed language, which then would have been translated into Chinook Indian trade language, and then into English. Smith's text is a necessarily filtered version of the speech and was certainly embellished by him.

Smith's rendering of Chief Seattle's speech was widely circulated and re-published over the years. Both Frederick James Grant and Clarence B. Bagley, pioneer historians, published the Smith version, in places adding or modifying it to suit themselves.

Several lines of the Chief's speech have become known throughout the world. For example, Smith has Seattle proclaiming: "When our people covered the whole land, as the waves of a wind-puffed sea cover its shell-paved floor. But that time has long since passed away with the greatness of tribes now almost forgotten." Another quote: "When our young men grow angry at some real or imaginary wrong, and disfigure their faces with black paint, their hearts, also, are disfigured and know no bounds, and our old men are not able to restrain them." And finally: "At night, when the streets of your cities and villages shall be silent, and you think them deserted, they will throng with the returning hosts that once filled and still love this beautiful land. The white man will never be alone. Let him be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not altogether powerless."

Henry Smith described Chief Seattle in several articles he wrote, including his re-telling of the 1854 oration. Nard Jones, in his book Seattle, suggests that the old chief may have been a real presence among the usually short-statured Duwamish and Suquamish Indians because, as Smith had written, Chief Seattle stood "six feet in his moccasins."

Transitions, Accumulations

Selling the bulk of his Seattle land for $75,000, Smith retained 50 acres for his personal use. His new wealth, and perhaps being a widower, encouraged him to explore new fields. In 1889, he built the London Hotel at the foot of Pike Street on Seattle's waterfront. A year later he built the Smith Block, later known as the Crown Building, at 2nd Avenue and James Street. Following the 1889 Seattle fire he built rental homes throughout Seattle. This investment activity caused Smith's fortune to grow, resulting in him at one time becoming King County's largest taxpayer.

The financial panic of 1893 caused Smith (and others) to suffer great losses. But even with reduced income and property, Dr. Smith continued to clear and plant lots in West Queen Anne. His fruit orchards and shrubbery remained a lifelong source of pride. He had been the first superintendent of King County public schools, built a steady medical practice, served as a loyal Republican in the territorial legislature, and helped Seattle become the Queen City of Puget Sound.

On August 16, 1915, surrounded by five of his daughters, Henry A. Smith died in his Seattle home at age 85.

Two stanzas (out of 22) of a Henry Smith poem are here reprinted from C. H. Hanford's Seattle and Environs:

PACIFIC'S PIONEERS

By Dr. Henry A. Smith

A greeting to Pacific's Pioneers,

Whose peaceful lives are drawing to a close,

Whose patient toil, for lo these many years,

Has made the forests blossom as the rose.

And bright faced women, bonny, brave and true,

And laughing lassies, sound of heart and head,

Who home and kindred bade a last adieu

To follow love where fortune led.