The city of Seattle was only 25 years old -- and Washington was not yet a state -- when a small group of pioneers organized the Young Men's Christian Association of Seattle. The town's emerging middle class recognized that Seattle had to outgrow its rough and tumble ways and begin thinking and acting like a civilized community if it was to realize its potential as a modern city. This file -- Part One of a four-part HistoryLink essay on the history of the YMCA -- looks at the organization's early years.

"A Genius for Adaptation"

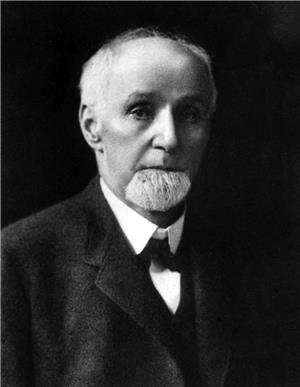

The fifteen men who organized the Young Men's Christian Association in the rough-hewn Seattle of 1876 would not recognize and probably would not approve of the YMCA today. Co-ed camping? Female board members? No preaching? Dexter Horton (1826-1904), the fledgling group's first president, thought it had begun to venture into dangerous territory with the opening of its first gymnasium in 1886. When asked to contribute to a fund for a building with a larger gym -- and a swimming pool -- two years later, he flatly refused. "No sir, not one cent," he said. "The Association has departed from the purpose for which it was organized, the spiritual uplift of young men, and now you propose to make it a gymnasium and a swimming pool. If the boys need exercise, let them saw wood, and if they want to swim, let them go into the Bay" (Kilbourne).

Yet at its core, the modern YMCA of Greater Seattle is guided by the same goals and values articulated when Horton and the other founders "associated to form a body politic" 125 years ago. The organization was started in Seattle (as in other cities) by a group of young men who turned to each other for support in maintaining their Christian faith, but embedded within their faith was a sense of responsibility for the temporal welfare of their fellow citizens. Their mission was to shape people who have a sense of self worth, take responsibility for the events of their own lives, care about each other, and serve their communities. This has been the polestar of the Seattle YMCA, through Gold Rush and Depression, war and peace, economic busts and booms, to the present day.

The organization has survived, and even thrived, because of what Wesley F. Rennie, its general secretary (chief executive officer) from 1933 to 1947, once called "a genius for adaptation." It has grown with the community and changed with the times, modifying policies and programs to adapt to shifting needs. It has carried on despite frequent criticism, both within and outside the organization, that it puts too much or too little emphasis on religion, tries to do too much or not enough, is just a big athletic club or a nest of radicals, thinks too narrowly or too broadly.

Those who participate in its programs today are not necessarily "Young" (nearly half of those served are older than 18); or "Men" (more than half are female); or "Christian" (the YMCA opens its doors to all). What remains is an "Association," still focused on the task, as mandated by the founders, of "extending aid and sympathy to all within reach of its influence."

Beginnings

Seattle in 1876 covered a scant five square miles. It had a population of fewer than 3,000, no sewers, little flat land (and much of that was often inundated by mudslides or high tides), frequent epidemics, many prostitutes, and few cultural amenities other than saloons. Most of the buildings were made of wood and none were more than three stories tall. There were no electric lights, no telephones, and virtually no social services.

It was in this environment that Horton, a onetime millhand and Seattle's first banker, called together a small group interested in organizing a Young Men's Christian Association. They knew of a similar group that had established the first YMCA, above a draper's shop in London, England, in 1844; of the retired sea captain who had brought the organization to Boston in 1851; and how the movement had spread to many other American cities, including Portland, Oregon, in 1868. Horton had visited the Portland YMCA, and was impressed enough by what he saw to propose that Seattle have one of its own. Fourteen other "young" men (Horton was 51 at the time) joined him in signing the Articles of Incorporation on August 7, 1876.

They began with Bible classes in a rented room. Their goal was to save young men from the free-flowing whiskey, the women of dubious reputation, and the other temptations of a frontier town -- to replace evil with good, immorality with Christian values, idleness with self-improvement. Although they were primarily interested in bringing men's souls to Christ, they soon took on the broader role of trying to ease the transition of the newcomers who were flocking into town, by helping them find jobs, housing, and social networks. Inevitably, their focus widened to include the boys who would become young men, and, eventually, the families from which they grew.

A scant two years after it was born, the Seattle YMCA was operating a library (with books inherited from the Seattle Library Association), sponsoring lectures and socials, and maintaining an informal employment agency, in addition to conducting twice-weekly Bible classes and prayer meetings. Members could look for hometown news in dozens of periodicals from around the country, including several published in Swedish and German, or relax with games such as chess, checkers, and crokinole -- a board game, similar to tiddlywinks, that was popular at the time. A boarding house directory was available for young men seeking respectable lodgings.

By the end of its first decade, the YMCA was operating Seattle's first gymnasium, equipped with "the latest approved apparatus," with a physician on hand to recommend personalized exercise regimens (not unlike a personal trainer today) (Bugle Call, February 1889). This was followed in short order by a bathing beach with a bathhouse and diving platform, on Elliott Bay behind the Y's rented quarters on what is today 1st Avenue, and an athletic field, on Cedar Street.

Physical or Spiritual or Both?

Each of these developments was justified as a way of promoting moral rectitude, under the theory that an active mind and a healthy body would reinforce spiritual vigor. The unity of mind, body, and spirit is an accepted concept today, symbolized by the familiar inverted triangle used as an emblem by YMCAs everywhere, but there was some initial resistance to the idea, particularly when it came to the gymnasium. Dexter Horton was not alone in thinking that the gym would distract the organization from the business of saving souls. After witnessing a gymnastics exhibition at the YMCA in 1888, Everett Smith, a lawyer who later became a King County Superior Court Judge, complained about being "subjected to nothing short of a genuine circus with the performers adorned in pink tights, gold and silver tinsel and, alas for the good name of the gymnasium, a full fledged clown with coarse jokes" ("History of the Y.M.C.A. in the Pacific Northwest"). Still, two years after it opened, the gymnasium was credited with boosting membership by 300 percent.

To its defenders, the gymnasium provided a harmless outlet for youthful energies, one that had the dual benefit of leaving participants both physically fit and too exhausted to engage in morally suspect activities. "It has been abundantly proven that a healthy, strong and able-bodied young man makes a better and more efficient Christian than one enfeebled and weak from any cause," C. A. Smith, chairman of the Gymnasium Committee, claimed in his annual report for 1890.

YMCA President A.S. Burwell pointed out that more and more young men were working in sedentary jobs and had no opportunity for physical exertion through their employment. Many were also working fewer hours, with more time for leisure activities. Better that they spend that time in "profitable exercise" than in the "Devil's traps" that were "open day and night, to ruin them" (Monthly Bulletin). If men could be enticed to exercise at the YMCA, they might be persuaded to join a Bible class or participate in other religious activities.

It was troublesome, however, that an average of 350 men were using the gymnasium every month while fewer than a dozen were attending the weekly Bible classes. The classes were moved from Wednesday to Saturday evenings in an effort to boost attendance, to little effect. "A great many more of our active members could be present if they would make an honest effort," lamented George Carter, general secretary from 1886 to 1893, in his annual report for 1887.

Practical Education

There was more interest in the YMCA's educational program, which evolved from a "Winter Course of Practical Talk Lectures" in 1886 to a few adult education classes in 1888 to a full-fledged college preparatory and vocational school by 1899. As a pioneer in the field of adult education, the YMCA sought to serve three types of students: those who had missed the opportunity for a general education, those who wanted specific technical training, and those who were simply interested in personal growth. Accordingly, the schedule of classes for the fall and winter of 1888 included German, arithmetic, bookkeeping, penmanship, "short hand and type writing," mechanical drawing and vocal music. Of these, the penmanship class was the most popular, since the typewriter was still something of a novelty and a legible hand was essential in business.

The vocational school -- first called the YMCA Night School and later the Association Institute -- was the first and for many years the most successful of its kind in Seattle. Initially, classes were held only at night, to accommodate the needs of students who had to work during the day. A Day School was added in 1907. The curriculum included a variety of fully accredited high school classes; graduates who passed an examination could get a certificate that could be used for entry into a college or university. The primary focus, however, was on what Harold A. Woodcock, longtime educational director of the Seattle YMCA, called "practical education -- the sort that equips the man for efficient work in some special department," such as bookkeeping or mechanical drawing (Seattle's Young Men).

In earlier eras, workers typically learned a trade by being trained on the job -- in the shop or store or on the farm. As the pace of industrialization quickened and the demands of the workplace became more complicated in the late nineteenth century, there was a greater need for specialized training. Seattle served as a magnet for thousands of young men from small farming communities and foreign countries. Many of the newcomers were poorly educated, leaving them "handicapped in the race of life in our city," as one report noted in 1893 (Bugle Call, June 1893). With its educational program, the YMCA committed itself to helping such men (and, much later, women) acquire the skills needed to succeed in a rapidly changing economy.

Finding the space to accommodate this widening array of programs was a constant challenge for the YMCA. The organization moved 11 times between 1876 and 1890, going from one rented building to another, usually occupying second-floor rooms above a factory or store, spaces that were often inaccessible and hard for a stranger to locate. Two of its early homes were destroyed by fire. In 1887, the Y launched a campaign to construct a building of its own, hoping to "once for all solve the problem of where we shall find suitable rooms for our work" (The Daily Press). Although only about half the required funds had been raised, excavation had begun when the Great Fire of 1889 burned down the Y's rented quarters at Front (now 1st Avenue) and Spring streets, along with most of downtown Seattle.

In the wake of the fire, the costs of construction soared and avenues of funding dried up. The price of brick, for example, tripled. Businessmen who had pledged to help finance the new building had little money left after covering their own losses. "Many of our staunch friends whose hearts were with us, and who had always responded generously to every call made upon them by the Association, were now utterly unable to continue the subscriptions they had usually made," A.S. Burwell, then chairman of the Finance Committee, reported at the end of the year (Bugle Call, September 1890). Directors of the YMCA borrowed $5,000 to complete part of the project but were not able to raise enough to finish it as designed. When the building -- the first to be owned by a YMCA in the Northwest -- was occupied in March 1890, it consisted of two stories, not the four that had been planned.

Still, the Y was justly proud of its new home. Built of brick at 1423 Front Street between Union and Pike streets, it included a gymnasium, game and reading rooms, a parlor, a large auditorium, and -- eventually -- Seattle's first indoor swimming pool, called for in the original plans but delayed for several years because of lack of money. The "swimming bath" or "natatorium" was filled with heated salt water piped up from Elliott Bay. Here men and boys swam naked in a spirit of unembarrassed fraternity, as was the tradition at all YMCAs until the advent of coeducational programs.

The new gym, "second to none on the Pacific Coast," included four rowing machines and an indoor running track. The reading room on the second floor boasted an unobstructed view of Elliott Bay and the Olympic Mountains, described with a certain lack of prescience as "a magnificent view which can never be intercepted" Bugle Call, February 1889). The auditorium, with seating for up to 600, quickly became a cultural center for the young city, used for public lectures, dramatic readings, and musical performances.

Edward C. Kilbourne, a prominent businessman and philanthropist (and a former dentist), headed the campaign to raise money for the building. Among the major contributors were James M. Colman, a pioneering engineer and developer (e.g., Colman Dock), whose son, Laurence, and grandson, Kenneth, also became key supporters of the Seattle YMCA; David T. Denny, a member of the party of Midwestern immigrants who founded Seattle in 1851; and Thomas Mercer, another early settler. Dexter Horton, true to his word, did not give one cent.

A few months after moving into the new building, the board of directors revised the Articles of Incorporation that Horton and the other founders had adopted in 1876. The new statement of purpose reflected the organization's expanded role: "The object of the corporation shall be the improvement of the Spiritual, Mental, Social, & Physical condition of the young men of Seattle by the support & maintenance of Lectures, Gospel services, Libraries, Reading rooms, Gymnasiums, Recreation Grounds, &c., Social meetings & such other means as may conduce to the accomplishment of this object" (Supplemental Articles).

The YMCA would no longer measure success solely by the number of young men who came to Bible and prayer meetings and confessed conversion to the Christian faith, although it continued to track those statistics. In his annual report for 1890, the chairman of the Committee on Religious Work counted 15 professed conversions and eight new church memberships during the year, a total, he noted with "a feeling of regret," that was far eclipsed by the number of people who had used the gym and swum in the pool.

To go to Part 2, click "Next Feature"