Calmar M. "Cal" McCune was a leading attorney and civic activist in Seattle's University District in the 1960s and 1970s. Born in Polk, Nebraska, in 1911, he moved to Seattle in 1932 to take law at the University of Washington and married Margaret Ann "Peg" Griffiths (Peg McCune, 1909-2008) in 1933. He began practicing in 1940 and built a successful firm, McCune Godfrey & Emerick, in the University District. McCune served as president of the University District Chamber of Commerce and Rotary Club and on the City of Seattle Housing Advisory Board and the City Planning Commission. He led efforts to preserve the Meany Hotel, to expand neighborhood housing and public parking, to ease tensions between U District merchants and young "street people" in the late 1960s, and to create a pedestrian mall on "the Ave" (University Way NE) in the early 1970s. Cal McCune published a memoir, From Romance to Riot, shortly before his death in 1996.

From Farm to Campus

Cal McCune was born into a family of independent-minded, hard-working Scots in Polk, Nebraska, a town founded by his father, on June 16, 1911. The family relocated to Haxtun, Colorado in 1919, where his free-thinking father established a farm, bank, and other businesses. The senior McCune went broke carrying the debts of his borrowers during the Great Depression, which also interrupted his son's college studies in Colorado and Nebraska.

The young McCune visited Seattle many times with his parents. There, he fell in love with Margaret Ann "Peg" Griffiths, daughter of his mother's closest friend and a Seattle City Council member. An uncle advanced McCune tuition to study the law at the University of Washington and he happily relocated in 1932. He worked his way through school with odd jobs and the graveyard shift at Wiseman's, an all-night diner on "the Ave" (14th Ave., now University Way, NE), which exposed him to the neighborhood's cast of Runyonesque characters.

Cal and Peg McCune married in 1933 and he graduated two years later. Positions for young attorneys were scarce, so he took a position at The Bon Marche department store. He worked his way up to assistant manager, and developed a stomach ulcer that would later exempt him from the World War II draft. In 1940, he left The Bon to join the law firm of Jones & Bronson.

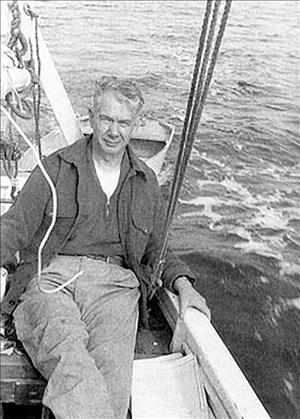

Life on the Water and Land

The McCunes were avid boaters. They bought their first vessel, a small cruiser named the Whimsey in 1942, soon followed by a aging motor yacht, the Anna Lou. They found cheap moorage ($25/year!) at the elite Seattle Yacht Club and moved aboard with their two young children, Leslie (b.1937) and Cal Jr. (b. 1939).

In 1948, the family moved to dry land with some regret, and Cal and Peg built their own home by hand in the Montlake neighborhood. The experience gave McCune special sympathy for the home improvement efforts of low-income residents as a member of the City's Housing Advisory Board, which oversaw early slum clearance and urban renewal programs in the Yesler-Atlantic neighborhood.

McCune earned respect in the University District business community and election as president of its Chamber of Commerce and Rotary Club during the 1950s. When U District merchants felt threatened by new Northgate and University Village shopping centers, he helped to organize a cooperative program for validated parking. He was also privileged to plead and win a case before the U.S. Supreme Court, but he was proudest of the fact that an annoyed Justice Hugo Black publicly called him an "S.O.B."

In 1955, McCune developed a new enthusiasm, flying. His far-ranging trips often took him south of the border, where he developed a connoisseur's eye for Latin American arts and crafts. This taste was shared by his daughter Leslie with whom he later established the La Tienda Folk Arts Gallery on the Ave (University Way NE).

McCune's civic involvements expanded during the 1960s to include membership on and chairmanship of the City Planning Commission. He was a leader in passage of new zoning rules intended, with great prescience, to concentrate high-density housing along major arterials and in established neighborhood centers -- what are called "urban villages" by today's planners.

Shock of the New

But the U District remained McCune's first love and primary concern as its unofficial "mayor" in the 1960s. He and the district initially welcomed the baby boomers who flooded the district as University of Washington attendance swelled in the mid-1960s, but merchants also feared the growing numbers of "Beatniks," "Fringies," "Hippies" and other Bohemian-wannabes who loitered on the Ave and filled early coffee houses such as the Eigerwand and Pamir House and used bookstores such as The Bookworm and The Id.

McCune initially sided with Ave merchants and helped to shutter or demolish the offending coffee houses, and demanded more intensive police patrols and drug enforcement as the sales of marijuana, LSD, and other psychedelics on the Ave became more overt. McCune was also deeply suspicious of the first campus-area student protests of the University District Movement (UDM), led by activists Robbie and Susan Stern and counterculture gurus Jack and Sally Delay (founders of "The Brothers," a self-help group based on San Francisco's Diggers).

Brahmin or Bohemian or Both

Yet McCune harbored some empathy for the District's young nonconformists and rabble-rousers, perhaps echoing his father, who defended the rights of local Catholics in Protestant Nebraska and opposed the Ku Klux Klan. Born under the Zodiac sign of Gemini (the Twins), he read copies of the city's first underground newspaper, the Helix, with equal measures of dread and admiration.

When The Id, a counterculture bookstore, was evicted in 1967, he quietly brokered its relocation to another U District storefront, and when beat cops harassed Black Panthers soliciting funds for a children's breakfast program, McCune intervened in their defense.

He enrolled for a philosophy course at the Free University, where anti-establishmentarians such as Trotskyist Miriam Rader, novelist Tom Robbins, and subterranean journalist Paul Dorpat lectured. McCune relished opportunities to debate local radicals in public forums, and often invited them out for post-combat beers so they could continue the exchange.

Wild in the Streets

McCune was also influenced by more liberal members of the business community, such as clothing store manager John Mitsules (an ally of future mayor Wes Uhlman) and Japanese American pacifist and merchant Andy Shiga (1919-1993), and local clergy such as the Rev. Dave Royer of Campus Christian Ministries. His conflicting sympathies were put to the acid test by the U District riots of mid-August 1969.

These disturbances were triggered by a police raid on an Alki Beach concert. The clash set the entire city on edge, and a minor confrontation on the Ave supplied the pretext for thousands of young people, who looted stores and battled frustrated police over several warm evenings.

Although angered by the vandalism and the damage to the image of his beloved U District, McCune was open to proposals for a truce among the U District's factions (although most of the trouble was caused by outsiders). With his help, John Mitsules, student body president Steve Boyd, and UW professor and radio host John Chambless persuaded police to permit citizen patrols to attempt to quiet the Ave. The technique worked and the crisis passed.

From Street War to Street Fair

There followed a long series of "negotiations" among merchants, "street people" led by poet-activist Jan Tissot, and other groups. Pressured by newly elected mayor Wes Uhlman and a widening payoff scandal, Police Chief Frank Ramon agreed to restrain the district's more zealous officers. The talks also laid the foundation for the U District Center, a social service agency that provided services and temporary housing for thousands of young transients in the early 1970s.

A fragile peace survived until May 1970, when the nation was shaken by protests against the U.S. invasion of Cambodia and subsequent killings of four demonstrators at Ohio's Kent State University. Campus demonstrations spilled onto the Ave, and police responded with uncommon brutality. McCune guarded his office cradling a shotgun, but when he descended unarmed to the street, he soon discovered that vigilante police, not rampaging radicals, were the real threat. He and U District Chamber President Dick Coppage were promptly handcuffed by plainclothes cops and bundled into a cruiser. When an assistant chief of police heard of the arrest, he ordered the police to release Coppage and that "mean son of a bitch" McCune.

The violence of the 1960s seemed to exhaust itself in the post-Kent State confrontations, and the U District celebrated with its first Street Fair (a brainchild of Andy Shiga) in late May 1970. It was a cheerless peace: the Ave was haunted by the walking wounded of the drug culture, and many traditional merchants gave up their hopeless resistance against shopping center competition and the influx of youth-oriented retailers and eateries.

The Last Crusade

McCune decided to mount one last counterattack to save the Ave. In 1969, he joined with Safeco Insurance president Gordon Sweany and UW vice president Ernie Conrad (student radical himself back in the 1930s) to organize the University District Development Council. It retained The Richardson Associates (TRA) architectural firm to draw up a master plan for the community's revival, and enlisted former Tacoma City Manager Dave Rowlands to coordinate the program.

With input from a Community Advisory Committee of residents, merchants and students, TRA crafted a proposal for a pedestrian mall on University Way, supported by peripheral parking structures and housing. Implementation would require property owners to raise their taxes by approving a Local Improvement District, and this drew heated opposition from apartment developer and landlord Don Kennedy. He hired distinguished but elderly architect Paul Thiry to critique the TRA plan and lobbied the district's mostly absentee property owners to reject the LID.

On December 16, 1972, McCune and mall backers conceded defeat. It was McCune's last great battle, but he hardly retreated from the scene. His law firm, McCune Godfrey & Emerick, was a leader in promoting women attorneys, for example, and gave future State Supreme Court Justice Faith (Enyeart) Ireland her first job.

McCune retired from active practice in the 1990s and began collecting his thoughts for a memoir of his life and career, titled From Romance to Riot and published in spring 1996. He was at work on a second book devoted to life and law as seen from the small firm when he died on October 16, 1996, following heart surgery at the University of Washington Medical Center. Cal McCune is survived by his brother Wesley, his wife, children, many grandchildren, and the neighborhood to which he dedicated his love and energy.

Editor's Note: Cal McCune's memoir planted seeds for (www.historyLink.org) -- this Website -- by bringing together editor Priscilla Long, graphic designer Marie McCaffrey, and long-time friend Walt Crowley for their first team project.