During the early twentieth century, America fell in love with the movies, and Seattle was no exception. It all began in December 1894 when Seattleites were introduced to Thomas Edison's newest invention, the kinetoscope, which was given a brief demonstration in the Pioneer Square area. After the turn of the century, local exhibitors began opening motion picture venues, first in the downtown area and later in the city's growing neighborhoods. By the end of the 1920s, which also marked an end to the great era of theater building, Seattle was dotted with hundreds of movie theaters, coming in all shapes and sizes, and scattered throughout the city.

The First Picture Shows

Virtually all early motion picture companies were located in the New York area, but Seattle wasn’t left in the dark when it came to demonstrations of early film technology. In December 1894, just nine months after it debuted in the East, Thomas Edison’s peep show novelty, the kinetoscope, got a weeklong exhibition in what was likely a vacant storefront at the foot of the Occidental Hotel.

Later, once the actual projection of motion pictures had been perfected, a number of touring shows brought their films and projectors to the Pacific Northwest. Most notable was an engagement of the “veriscope” projector at the Seattle Theatre, corner of 3rd and Cherry, in August 1897, which headlined with scenes from that year’s heavyweight fight between James J. Corbett and Robert Fitzsimmons.

Before long, the city had a handful of regular movie houses -- later dubbed nickelodeons -- to call its own. By 1902, Edison’s Unique Theatre had opened on 2nd Avenue, while Le Petit Theatre operated around the corner, at 222 Pike Street. At the same time, just a few blocks away, future theatrical magnate Alexander Pantages (1876-1936) made films a regular part of his bills at the Crystal Theatre, the first of many vaudeville houses he would operate throughout his lifetime.

Small venues such as Edison’s Unique and Le Petit had relatively short lifespans, but before long Seattle’s first more-or-less permanent movie houses began to appear. With names like the Bell, the Bijou, the Odeon, and the Dream (reportedly the first house in the United States to install a pipe organ for musical accompaniment), the growing popularity of motion pictures with Seattle audiences was plainly evident.

By 1908, in a six-block span of 1st and 2nd avenues, there were no less than eight storefront theatres in operation, with more in the works. "The cheap moving picture houses are at last invading Seattle in numbers,” one local dramatic critic lamented that year, “and soon the main thoroughfares will be lined with them. Three or four are now being made ready on Second Avenue, between Madison and Pike Streets” (Sayre).

Challenging the Legitimate Stage

After 1910, increasing sophistication in motion picture production and distribution not only made movies more popular with the public, but also a more profitable venture for local exhibitors. This coming of age was demonstrated in 1911 when the Alhambra, a stock and vaudeville theatre which had opened two years earlier, was converted to show motion pictures exclusively.

Undertaken by C. S. Jensen and John G. von Herberg (1880-1947), the move was the first serious attempt in Seattle to put films on equal footing with the stage, at the time the city’s largest form of popular entertainment. In some respects, the effort failed -- Jensen and von Herberg converted the Alhambra back to a vaudeville house within five years -- but the gamble was nonetheless a sign of the times. The motion picture was here to stay, and it was beginning to compete for the same audiences as traditional stage plays, vaudeville, and stock theater.

If theaters alone are an indication of popularity, then Seattle audiences really took to the movies between 1910 and 1915. When James Q. Clemmer opened the Clemmer Theatre at 1414 2nd Avenue in 1912, it was the first large venue in Seattle constructed solely for presenting motion pictures. Jensen and von Herberg failed to keep the Alhambra going, but nonetheless built the Liberty Theatre in 1914 across from the Pike Place Market, which boasted a seating capacity of 1,700. Two years later they topped themselves by opening the Coliseum at 5th and Pike, at the time dubbed the finest motion picture house west of the Mississippi. The Coliseum was designed by local architect B. Marcus Priteca, soon to become the nation’s leading designer of stage and film venues.

Other large downtown houses, such as the Class A (opened in 1911), the Colonial (1913), the Mission (1914), and the Strand (1915) further demonstrated the growth of motion picture entertainment. By the time D.W. Griffith’s Civil War epic The Birth of a Nation ended a record-breaking five-week run at the Clemmer in July 1915, there was no denying that motion pictures had become a formidable challenger to the legitimate stage.

Coming Soon to a Theater Near You

The damage that motion pictures wrought against the city’s stage venues was not simply because they were more popular, but because they were becoming more accessible. Once the downtown and Pioneer Square areas were saturated with first-run houses, exhibitors began opening smaller, often second-run theaters throughout Seattle's growing neighborhoods.

Ballard lead the way, with no fewer than three motion picture houses (the Ballard, Crystal, and Tivoli) running as early as 1910. But other neighborhoods were not far behind. By 1912 Queen Anne had the Queen Anne Theatre; West Seattle had the Olympus; and the Rainier Valley had the Valley, for example.

Only a handful of these early neighborhood theaters became permanent fixtures in the community (in Ballard’s case, only the Ballard Theatre operated through World War I), but it was a trend that gradually changed the recreation habits of Seattle audiences. Provided one didn’t mind seeing a second-run feature, the convenience of the local picture house often won out over a streetcar ride to one of the larger downtown venues.

Over time, this trend brought about a decline in patronage for Seattle’s larger theatres (stage and screen alike), so that by the 1950s and 1960s many of the city’s once-glorious downtown theaters had been torn down or closed. At the same time, the neighborhood movie theater trend continued to flourish. Some of these theaters are still in use today: the Neptune in the University District (opened in 1921), the Paramount in Wallingford (1922, now more widely known as the Guild 45th), and the Uptown in Queen Anne (1926).

The Changing Landscape

The 1920s was Seattle’s most active decade with respect to theater construction, but it also saw the two events that brought this era to an abrupt halt. The coming of sound films in 1927 (with John Hamrick’s Blue Mouse Theatre leading the way, showing both Don Juan and The Jazz Singer that year) prompted numerous local theaters to invest in sound technology, an expensive proposition. This, coupled with the onset of the Great Depression in October 1929, brought local theatre construction to a virtual standstill, save for the occasional renovation of an existing house.

Seattle’s large downtown venues and neighborhood theaters continued to play to capacity audiences until changing economics forced the demise of many. As the audience base began to shift out of Seattle proper and into the suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s, newer screens were erected to cater to people's entertainment needs. Later, with the development of multiplex theaters, many of the city’s once-impressive movie houses fell victim to the wrecking ball.

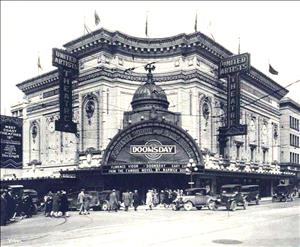

Seattle can take pride in the preservation of such early movie houses as the Paramount or the Fifth Avenue. Still, the preservation of the city's older theatrical venues has been the exception, not the rule. In many cases, all that remains of these venues are a few old photographs and memories of Saturday afternoons well spent.