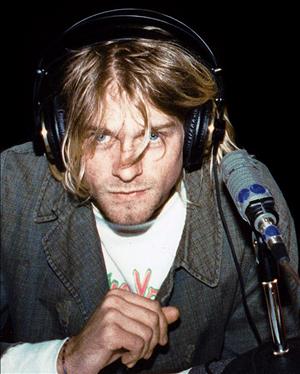

Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) was the lead singer of the Seattle grunge band Nirvana. He commited suicide in 1994. In this People's History Clark Humphrey reflects on his life and music.

Kurt Cobain: The Life and the Legacy

Fans still regularly leave flowers on a graffiti-laden bench in Seattle's Viretta Park, the only public (albeit unofficial) memorial to Kurt Cobain. It was on a rainy Friday morning in early April 1994 when hundreds of fans had originally gathered at this park, next door to the house where Cobain took his own life, leaving behind a wife, a child, a band, and a musical legacy.

They're remembering a young man whom nobody apparently expected would go far in life. He was reared in the small, economically-depressed timber town of Aberdeen, with several forebearers who'd committed suicide. He was both intelligent and disinterested in sports, in a jock-culture environment that scorned boys of that sort.

From Aberdeen to Major Label

The teenaged Cobain became part of what little indie-rock scene there was in Aberdeen, which centered around a band called the Melvins. That clique also included Chris (later spelled Krist) Novoselic, who moved with Cobain to Olympia once they turned 18.

They played with assorted drummers and band names, finally settling on Nirvana by the time they appeared at the old Vogue nightclub in Seattle on a Sunday-night gig in early 1988. By that time, they'd released a single on Sub Pop and were about to record their debut album Bleach.

Through 1989-1990, Nirvana's performances became sharper and Cobain's songwriting became more layered and elaborate. But the strain of maintaining an indie-label act, with precarious finances and limited record-label support, began to take its toll (a European package tour with Mudhoney and Tad proved particularly grating for Cobain). Instead of recording a second Sub Pop album, Nirvana hooked up with a manager who got the band signed to a major label.

Loud, Angry, Punk ... and Melodic

The bucks showed in the much slicker pop-rock production of the band's next album, Nevermind (and also in the videos and tours supporting it). But slicker production wasn't Nevermind's only difference from Bleach. It was both a loud, angry punk album and a punchy, melodic pop album. Its smash worldwide success surprised everyone including the record label, which promptly arranged more and more tour dates.

Cobain and Courtney Love had first met at an early Nirvana gig in Portland, and toured together behind Sonic Youth in the pre-Nevermind months. But it was on the grueling year-and-a-half tour supporting Nevermind that they became a couple.

Courtney and Kurt

Born in California to an early, minor associate of the Grateful Dead, Love grew up in various states and countries (but most notably in Portland, where her mom was a psychologist). She was once put in a boarding school as an attempt to contain her wildness. She was later a stripper in Alaska, a music-scene hanger-on in Portland and San Francisco, and an occasional actress (most notably in Alex Cox's spaghetti-western send-up Straight to Hell). In Los Angeles she started the band Hole with guitarist Eric Erlandson.

The Kurt and Courtney relationship quickly became a bigtime media circus: the gossip, the magazine covers, the road behavior, the pregnancy, the private wedding, the public squabbles.

From all accounts and quotes, Love had long wanted to become a genuine multiplatinum Rock Star with all the perks (limos, magazine covers, press agents, etc.). But Cobain never did. He wound up becoming one anyway, and it helped to destroy him.

The media reinterpreted his anti-corporate persona as just another bad-boy image to sell merchandise, and how he hated what he'd been turned into. Addded to that were the stress of being the locus of a multi-million-dollar enterprise and a global celebrity hype subject. He retreated further into a private world.

Kurt's Private World

At the heart of his private world was an initially denied, but increasingly obvious, heroin habit. Cobain never publicly celebrated or advocated drug use, but by the time In Utero finally came out his songwriting (and his influence in the band's cover art and videos) had come to reflect a heroin-inspired aesthetic, with images of enveloping inner calm and numbness amid danger and harshness.

He tried to get off the junk, repeatedly. In late 1992 he went through an inpatient withdrawal program in the same hospital where Courtney was giving birth to their daughter Frances Bean Cobain. He felt well enough that he agreed to another worldwide arena tour to support the next Nirvana album, In Utero. Breaking from the high-energy anthems of Nevermind, In Utero offered slowed-down ballads of defiance and despair, immoderate statements at moderate tempos.

The tour, particularly a six-week European stretch, ruined him. It ended abruptly with an announcement that he'd lost his voice and couldn't continue. Days later, he was hospitalized in Rome, in a coma after an apparently deliberate overdose of cold pills accompanied by alcohol.

Upon his recovery, Cobain returned to Seattle, to the Viretta Park house he and Love had bought (near that of Starbucks Coffee CEO Howard Schultz).

The Intervention

There, Love and friends performed an "intervention" on Cobain, confronting him en masse and persuading him to enter a residential rehab program in California.

One day while Love was in Los Angeles planning promotions for Hole's album Live Through This, Cobain walked away from the rehab program and disappeared. Love, Novoselic, and friends started a discreet search. They apparently didn't think of looking in a garage building behind the Cobain-Love house, where, sometime on April 5, he wrote a suicide note, took some heroin, and shot himself in the mouth.

It took three days for Cobain's body to be discovered, by a workman at the Viretta Park house. Once radio stations announced the discovery, shortly after 11 a.m. on a Friday, hundreds thronged to the house and the neighboring park. Some stayed there throughout the weekend.

That Sunday afternoon, nearly 10,000 fans attended a public memorial at the Seattle Center Flag Plaza. At the memorial, audio-taped remarks by Love and Novoselic were played. Love denounced her own failed intervention on his behalf, saying she wished she had "let him have his numbness."

Novoselic's less emotional message asked fans to remember Cobain's "ethic toward his fans, that was rooted in the punk rock way of thinking: No band is special, no player royalty. If you've got a guitar and a lot of soul, just bang something out and mean it. You're the superstar, plugged into tones and rhythms that are uniquely and universally human; music .... That's the level that Kurt spoke to us on, in our hearts."

Voices of a Generation

This spirit represents a big part of why Cobain and Love's works were and are still important: Besides being alleged Voices of a Generation, they represented the last (for now) triumph of real, street-level, unabashed and uncompromised rock n' roll. But they also carried a message of hope, even when singing about despair. They were populists who celebrated a close-knit subculture of people who intensely cared about taking control of their culture and their lives.

Courtney Love is now back in Los Angeles, working as a film actress and sometime fashion model. She's put her musical career on hold while taking legal action to get out of her record contract. (During the height of the Kurt and Courtney mania, she'd been more amenable to "being a rock star" than Cobain; now she's as adamant as he was about the corporate music business's inherent corruption.) Krist Novoselic helps run the musicians' activist group JAMPAC, and led a late-1990s band called Sweet 75. Nirvana drummer Dave Grohl now leads the band Foo Fighters and lives in his home state of Virginia. Frances Bean Cobain, now nine, has been successfully kept out of the public spotlight.

Cobain was cremated; the cremains are kept in an undisclosed private location. His family has yet to approve of any official memorial site. And he may not have wanted to be remembered that way, as some larger-than-life icon. He wanted to touch souls with a message, to inspire people to create their own culture. The personal, heartfelt remembrances carved into the "Kurt's Park" bench might be the most appropriate memorial he could have.