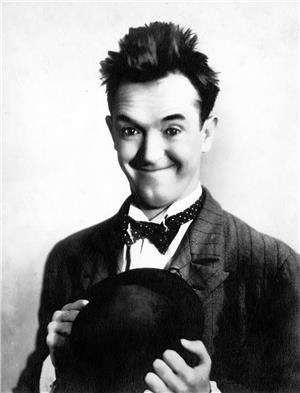

Beginning March 18, 1917, nearly a decade before he would become a prominent comedic figure, Stan Laurel (1890-1965) plays a four-day vaudeville engagement at Seattle's Palace Hip (short for Palace Hippodrome) Theatre. After visiting Seattle on no less than four previous stage tours, each in minor comedy roles, the 1917 visit marks the comedian's first known local engagement as a solo vaudeville act. Stan Laurel would eventually gain lasting fame in the films he made with Oliver Hardy (1892-1957) from the late 1920s through the early 1940s.

It Runs in the Family

Stan Laurel was born Stanley Jefferson in Ulverston, located in northern England, on June 16, 1890. For years his father Arthur had been an actor, playwright, manager, and director on the English stage, and his mother, Madge Metcalfe, was Arthur's leading lady. Many of Arthur's plays, it seems, were staples on the English circuit and quite popular with the audiences of the day. Although born into a stage family, Stan was encouraged by his father to enter the field of theatrical management, an effort to spare his son the hardships faced by traveling performers.

Stan had other ideas. An affinity for stage comedy led him, in 1906, to develop his own stage routine, and unbeknownst to his father, Stan used family connections to try out his act on a local stage. On his first night, according to legend, Stan's father happened to attend the same theater, and was shocked by his son's sudden appearance. But rather than become angered by his son's rejection of a stable career in theatrical management, Arthur Jefferson instead recommended that Stan further develop his comedic talents.

Over time, Stanley Jefferson caught on in small roles with Levy and Cardwell's Pantomime Company, working his way from extra to lead comedian. This experience eventually brought him to a comedy troupe run by Fred Karno, the same organization where Charles Chaplin got his big break on the English stage. Jefferson spent several years with the Karno organization, touring not only England but North America as well.

On the American leg of these tours, Stanley Jefferson was Chaplin's roommate, in addition to serving as the comedian's understudy. On all four of Charles Chaplin's known stage visits to Seattle (two in 1911, two in 1912), Jefferson played small and unassuming roles in the background, waiting for the opportunity to headline himself. When the exceedingly popular Chaplin left Karno for a film offer with Mack Sennett's Keystone Studios, Fred Karno's American vaudeville troupe disbanded. Stanley Jefferson was free to begin making a name for himself.

Going Solo

As Stan Laurel -- the comedian changed his last name shortly after leaving the Karno troupe -- his initial efforts in vaudeville were directly linked to the success Charles Chaplin was achieving in motion pictures. After all, who better to present an imitation of Chaplin's antics to vaudeville audiences than his former understudy?

Eventually, however, the comedian began to develop his own comedy material, and on March 18, 1917, at the Palace Hip (formerly known as the Majestic and Empress, where the Chaplin-led Karno troupe had played their local engagements), Stan Laurel brought his own act to Seattle. At the time, he was aided by Mae Laurel (nee Dahlberg), his commonlaw wife, in a rollicking skit called Raffles, the Dentist. The playlet centered on the plight of a burglar who breaks into an apartment only to find its occupant, a lovely young woman with a toothache, mistake him for the dentist she had sent for earlier.

The sketch, according to reviews, was a variety show in itself -- into the basic scenario the pair somehow managed to weave comedy, music, and dance. It was an odd mixture from the sounds of it, but was nonetheless greeted with applause by Seattle audiences, in what was ultimately a brief stay. Unlike when the Karno troupe had appeared at the same theater, the Palace Hip's new policy was to change bills twice a week, on Sunday and Thursday. The Laurel sketch occupied a featured position on the Sunday-Wednesday bill, competing for attention with, among others, the eighth chapter of the Francis X. Bushman/Beverly Bayne film serial The Great Secret, a pair of singing and dancing acts, and a duo who called themselves The Spanish Goldinis, identified as "rug jugglers."

Stan Laurel's association with Chaplin, which press notices mentioned frequently, had a double edged aspect. Early on, this association helped assure audiences of Laurel's talents, but it also drew obvious and sometimes unflattering comparisons between the two performers. Indeed, Laurel's act at the time seems to have been more in line with the Chaplin style of comedy (more precisely, the Karno style of comedy) than the type he would perfect in later collaborations with Oliver Hardy.

Reviews for the 1917 engagement of Raffles, the Dentist tended to bear this out. Although he wasn't the headline attraction (a high-wire act took those honors), Laurel's sketch was greeted favorably, if only respectfully. "Stan and May [sic] Laurel present a skit called Raffles, the Dentist, in which they have also singing and dancing besides a lot of Charlie Chaplin comedy that is funny," noted the Daily Times. "Laurel was not long ago the understudy for Chaplin, and is an expert at the latter's kind of acrobatics."

Charles Eugene Banks, writing for the Post-Intelligencer, also noted the connection between the two comedians, although he was a little more appreciative of Laurel's gifts. "For those who like the comedy style of Charlie Chaplin, the offering of Stan and May [sic] Laurel will come as a real treat. They present a medley of entertainment which includes a skit called Raffles, the Dentist, singing, dancing and comedy. The antics of Mr. Laurel, who was formerly an understudy for Chaplin, are a scream for that type of acting. His song, 'I'm a Burglar' is exceptionally funny, and Miss Laurel's dance and burlesques are good" (Banks).

As a pair, Stan and Mae Laurel continued to tour for several years with their vaudeville act (which was eventually renamed No Mother to Guide Her), and they returned to Seattle on no fewer than three occasions: at the Palace Hip in 1918, and at the Pantages in 1919 and 1921.

Abandoning the Stage

As a stage performer, Stan Laurel was nearing the end of his vaudeville career by the early 1920s. As his father had originally feared, the itinerant lifestyle of the traveling performer had worn considerably on him, and with stage opportunities becoming more and more scarce, motion pictures looked like an increasingly viable outlet for his talents. After several false stars, in 1926 he signed with Hal Roach Studios, where he first discovered his talents behind the cameras, although he occasionally performed in front of them as well.

Eventually, he was paired opposite Oliver "Babe" Hardy, a small-time film comedian with more than a decade of film experience behind him. Interestingly, it wasn't their first meeting. At some point during the teens -- between the comedian's first solo Seattle engagement in 1917 and his third in 1919 -- Laurel had managed to make at least one comedy film for the Metro Studios in Hollywood. That film, Lucky Dog, cast Laurel as a hapless young man who stumbles upon a lost pooch, enters it in a local dog show but, in the process, runs into its rightful owner. Over the course of the picture, Stan's character almost becomes the victim of a petty crook, although he manages to outwit his opponent and scamper away. The crook was played by Oliver Hardy, their moment together onscreen occurring a full decade before their "official" pairing at the Hal Roach Studios.

The Dynamic Duo

As a comedic team, of course, Laurel and Hardy would make a number of shorts and features from the late 1920s through the early 1940s. Their short The Music Box was named Best Live Action Short Subject at 1932's Academy Awards ceremonies. Later efforts included such popular feature films as The Flying Deuces (1939), A Chump at Oxford (1940), and Saps at Sea (1940). Following the close of their film acting careers, both comedians made highly publicized tours of the English music hall circuit, once in 1947 and again in 1954. Following Oliver Hardy's death in 1957, Stan Laurel gave up performing altogether.

Stan Laurel received an honorary Academy Award in 1960. He passed away in February 1965.