For more than 50 years, some of the world’s most spectacular fireworks came from a collection of sheds on a hill in Columbia City, home to a pharmaceutical chemist with a genius for pyrotechnics, a talent for showmanship, and a child’s delight in things that boom, flash, fizz, and sparkle in the dark. Ever-stringent fire and safety regulations gradually pushed the Hitt Fireworks Company out of business in the 1960s, leaving only memories of what poet Arlene Naganawa called "the ruby flash" that "consumed the dark, then feathered into ash."

Boom! Bam! Whizz!

Thomas Gabriel Hitt (1874-1958) was a British émigré who began tinkering with fireworks while studying chemistry at Westminster College in his native London. According to a family story, Hitt almost got kicked out of his “proper English college” for making fireworks and storing them under his bed. He worked as a pharmacist in London after graduating in 1895, with a degree in pharmaceutical chemistry, but continued experimenting with explosives.

Hitt left London in 1899, when he emigrated to Victoria, British Columbia. He ventured into the fireworks business for the first time in Canada, establishing the Hitt Brothers Fireworks Company with a younger brother, Fred G. Hitt. The two brothers eventually settled in the United States. "T. G." (as he was known to his family) moved first, in 1905, to Columbia City, where he founded the Hitt Fireworks Company, which soon became one of the nation’s leading manufacturers of fireworks. Fred later opened his own company, specializing in the production of railroad flares, in Los Gatos, California.

Columbia City in the early 1900s was a bustling, independent mill town with many attractions for an entrepreneur like Hitt, including low taxes, inexpensive land, and good railway service to Seattle. Hitt and his wife, Annie Eliza Bull (whom he had met in London) bought four acres in what was then an uninhabited part of town. The wooded hillsite, bounded by 37th and 39th streets S and S Brandon and Dawson streets, offered the space and isolation Hitt needed to test and manufacture fireworks without bothering any neighbors.

By 1911, the business was doing well enough that Hitt incorporated it, as the Strontia and Chemical Manufacturing Company, with a capital stock of $6,000. Two years later, he changed the name, to Hitt Fire-Works Company (dropping the hyphen some time after that).

The Burning of Atlanta

Hitt, joined in the 1930s by his son, Raymond C. Hitt (1906-1998), specialized in elaborate pyrotechnic “set pieces” recreating famous historical events, such as “The Fall of Babylon” and “The Last Days of Pompeii.” The displays were created on huge wooden frames, up to 400 feet long and 75 feet high, designed to be seen from a distance. A favorite in Seattle was a depiction of the Great Fire of 1889. Scenes from early Seattle were painted on a 100-foot long set and embedded with fireworks. When ignited, the buildings seemed to be outlined with dots of fire, which grew to engulf the city.

The shows were larger-than-life productions, with chorus girls or military drill teams performing between explosions. Each one ended with a grand finale in which the set appeared to blow up into a ball of fire, lighting up the skies with bursts of color and showers of rockets.

It was this kind of showmanship that apparently brought the Hitts to the attention of Hollywood. Drawing on their experience in building and then burning down sets, the Hitts created special effects for scenes in several blockbuster movies, including the famous burning of Atlanta in Gone With the Wind, the battle scenes in All Quiet on the Western Front, and the fire and explosions in What Price Glory?

In addition, the company produced elaborate aerial displays for Fourth of July celebrations, world's fairs, and commercial extravaganzas all over the country. Hitt fireworks launched the opening of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle in 1909, the Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915, the Philadelphia Sesquicentennial in 1926, and the New York World’s Fair in 1939, among others.

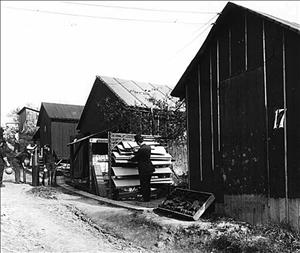

Using the proceeds from the San Francisco spectacle, Hitt and his wife built a large home next to their factory, which consisted of about 30 individual manufacturing and storage sheds, spaced at a distance intended to minimize the risk of fire spreading from one shed to another. They named the property Morningside Acres but nearly everyone else called it Hitt’s Hill. The house was surrounded by English-style flower gardens, tended by Hitt’s father-in-law, James Bull. There was a grass tennis court and a fish pond. It was a serene environment for the production of things that fumed, smoked, sparkled, and exploded.

In Seattle, it hardly seemed possible to celebrate the Fourth of July without Hitt fireworks. Beginning in 1918, with a display featuring a 300-foot replica of Flanders Field at the University of Washington football stadium, and ending in 1974, with an aerial production sponsored by Ivar Haglund on Elliott Bay, the company was associated with every major Fourth of July fireworks show in Seattle.

The company’s commercial division also produced smaller shows, usually using fireworks manufactured elsewhere but orchestrated by Hitt’s staff of pyrotechnicians. Locally, these included fireworks displays during the Seward Park Pow Wow, the Green Lake Aqua Follies (a Seattle summertime fixture from 1950 to 1964), and the summer festivities at Playland (a popular amusement park that operated from 1930 to 1960 at Bitter Lake, in the Broadview neighborhood).

Flashcrackas

While the company’s reputation was built on its dazzling public shows, its bread-and-butter business came from the sale of small novelties such as “Flashcrackas” (small firecrackers), Roman candles, snakes, sparklers, coils of “caps” for toy pistols, and “Witches Flames” (crystals that created multicolored “Magic Fairy Flames of Rainbow Tints” when thrown onto a fire). The company also manufactured marine, railroad, and highway flares, mole extermination devices, and a special firecracker designed to protect mail-carriers from unfriendly dogs (called "Doggone"). If it was noisy, smoky, or fizzy, it was on Hitt’s product list.

The best-selling retail item was the Flashcracka, which T. G. Hitt developed in 1916. The firecracker market up to that point had been dominated by the Chinese, whose experience with pyrotechnics dates back to the sixth century. The so-called “mandarin” firecrackers were made with black powder composed of potassium nitrate, sulfur, and charcoal. Hitt substituted photographic flash powder, a mix of powdered magnesium or aluminum and an oxidizer. His “flashlight crackers” exploded with a much louder noise than their black powder predecessors.

Flashcrackas were a key ingredient in Spokane's annual Firecracker Golf Tournament, held at the Indian Canyon Golf Course from 1936 through the 1960s. In this event, described as "the most tumultuous ear-splitting golf tournament in the world," competitors teed off and played amid a cacophony of exploding Flashcrackas, sirens, bells, and horns. Authors Bruce Nash and Allan Zullo included it in their Golf Hall of Shame.

"For golfers it was like playing through a firefight in the streets of Beirut," they wrote. "The booms, bangs, and blasts startled players out of their strikes, shattered their nerves, and helped send their scores soaring as high as a Roman candle" (133).

Hitt’s took a certain pride in its role in staging the event, and used footage from one of the tournaments in a promotional film (an excerpt is posted above).

Hitt eventually shared his formula with the Chinese. In return, Chinese manufacturers began mass producing Flashcrackas.

In addition to producing for the domestic retail market, the company also sold to a large foreign market, thanks in part to W. E. Priestly, its traveling representative from 1909 through the 1930s. Priestly, a second cousin of T. G. Hitt, made 12 trips to China and many more to Canada, Mexico, Japan, the Philippines, and Hawaii, helping make the Hitt brand known internationally as well as nationally.

The company survived, and even thrived, during the Great Depression. “People needed entertainment,” says Gloria Hitt Cauble, whose father, Raymond C. Hitt, eventually took over the family business. “Fireworks didn’t cost much. They were patriotic, too” (Cauble Interview).

Smoke Screens

During World War II, the company shifted to military production, manufacturing parachute flares (which are fired into the air and then descend by parachute, illuminating the ground) and other safety devices. Hitt Fireworks also produced aerial smoke screens that were used to help camouflage the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard at Bremerton.

Meanwhile, T. G. Hitt applied his skills in chemistry to his hobby of perfumery. In his basement “la-BOR-atory” (his granddaughter, Gloria Hitt Cauble, says he always used the English pronunciation), he experimented with extracting scents from the flowers that surrounded the family home. He developed about 30 scents in all, selling them in a shop downtown under the DeGlaceme trademark. He used Northwest themes in naming his perfumes: Glacial Lily, Northern Clematis, Northwest Lilacs. However, the perfumes weren’t as popular as the fireworks. Hitt concluded that women preferred perfume with Parisian labels.

At its peak, in the 1930s, Hitt Fireworks employed up to 200 workers on Hitt’s Hill, one block west of Rainier Avenue S. However, as Columbia City became more urbanized, it became less hospitable to a fireworks factory. A fatal explosion in 1921 (which killed a woman working at the plant) dramatically underscored the dangers of manufacturing fireworks in what had become a residential area. Several smaller explosions led to fires, which caused minimal damage because of the spacing between the sheds but which nonetheless alarmed fire and other officials. The city passed increasingly stringent limits on the type of fireworks that could be produced at the plant, eventually banning the manufacture of fireworks within the city limits. More and more of the manufacturing business was shipped overseas, to China and the Philippines.

After T. G. died, in 1958, his son Ray continued to operate Hitt Fireworks but it was clear that the glory days were gone. Insurance costs escalated, along with property taxes and pressure from local and federal safety regulators. “The fire department was after them all the time because they were in the middle of a residential area,” says Gloria Hitt Cauble. “But the factory had been there first. When T. G. started, he was up on a hill all by himself” (Cauble Interview). Ray Hitt, bitter about the tightening web of regulations, complained that “They’ve taken the independence out of Independence Day” (Rainier Valley Historical Society).

Ray Hitt gradually shut down the factory in the late 1960s, although he continued to do a little business by himself, as a licensed pyrotechnician. For example, he set off fireworks to announce the opening of fishing derbies and the batting of home runs at Sicks’ Stadium. He oversaw his final Fourth of July display for Ivar Haglund in 1974. Finally, in 1977, facing a tax bill he couldn’t pay, he closed the business altogether and (with his brother Wilmott) sold the site of the factory on Hitt’s Hill. He died in 1998, at age 92.

Hitt’s Hill

The family home remained in the family, and is occupied today (2001) by Gloria Hitt Cauble. Cleaning out the basement some years ago, she discovered a treasure trove in what had been T. G.’s “la-BOR-atory.” She donated what she found to the Rainier Valley Historical Society. Beakers, canisters, cartridges, labels, posters, and other memorabilia from a half century of fireworks manufacturing in Columbia City are now on display at the society, in the Rainier Valley Cultural Center, 3515 S Alaska Street.

The factory site has remained largely undeveloped, the sheds swallowed up by blackberries, ivy, and big-leaf maples. A neighborhood group, Friends of Hitt’s Hill, has been working with the City of Seattle and the King County Council to acquire the property and adjacent parcels -- totaling three-and-a-half acres, now owned by a developer -- and turn it into a park. The City has budgeted $700,000 and the County $200,000 for the project; the neighborhood group is trying to raise an additional $85,000 from private sources to buy the land.

If the project succeeds, Hitt’s Hill will become an urban refuge, cleared of ivy and blackberries, replanted with Northwest native plants, with benches and paths offering distant views of Lake Washington, downtown Seattle, Mount Baker, and the Cascades. The preservationists envision a “passive park,” providing badly needed open space in a neighborhood increasingly under pressure by developers -- a spot that could invite visitors to pause for a moment of quiet reflection on the hill’s noisy past.