The Haller Lake community dates back to 1905, long before it was part of Seattle. Today it stands squeezed between Aurora Avenue N and the Interstate 5 freeway, and runs northward from N 110th Street to the current city limits at N 145th Street. Were it not for the physical and psychological presence of the freeway, the neighborhood would likely claim the Jackson Park golf course as its own. Similarly, the speeds and noises of Aurora Avenue N cut it off from its sibling, the Broadview/Bitter Lake neighborhood to the west. Nevertheless, with a 15-acre lake at its center, and with large lot sizes to remind visitors of its farmland past, the community retains a unique character among the many neighborhoods that constitute contemporary Seattle.

Haller's Lake and Haller's Land

The first settler in what became the Haller Lake neighborhood was John Welch, a British subject about whom little is known. Welch submitted an application for a 160-acre homestead to the territorial Land Office in Olympia on April 19, 1869, for the area now bounded by 1st Avenue NE, N 120th Street, Ashworth Avenue N and N 130th Street. He became a United States citizen on August 10, 1870, and lived on the homestead continuously from the fall of 1870. The 15-acre lake that was the centerpiece of the homestead became known as Welch Lake (sometimes misspelled Welsh) in Seattle land records.

In 1905, Theodore N. Haller (1864-1930) bought the property from Welch and platted a cluster of lots around the lake, which took on the name of its new owner. Haller was the son of an army colonel assigned to duty in the Pacific Northwest. The colonel arrived at Fort Vancouver in 1853, and later settled in Seattle with his military pension. He proceeded to amass substantial holdings of prime agricultural land in nine Washington counties, along with valuable business properties in Seattle.

After his father's death, the younger Haller made his career managing his father's complex estate from offices in the Haller Building in downtown Seattle. The Haller Lake Tracts, likely the first plat filing in the area, were part of these activities.

Clare Huntoon's Land

Plat filings by other land owners followed in 1908 and 1909, but most came later, some as late as 1947. The widow Clare E. Huntoon, who arrived in Seattle in 1918, owned nearly 200 acres of real estate in the Haller Lake area, which she never platted.

She was long gone from the scene before the land was developed, but later use of her land is historically important to the area. Ingraham High School and Haller Lake Playground (Helene Madison Pool) were built on 36 acres bordering Meridian Avenue N at 130th Avenue N. Huntoon also owned land along the west side of the North Trunk Road (Aurora Avenue N) on which subsequent owners built Playland, and an adjacent auto race track that operated until the 1950s. Northwest Memorial Hospital sits on 33 of her 146 acres neighboring the south and east sides of Haller Lake. The commercial property at the intersection at N 130th Street and Aurora Avenue N is part of Huntoon's original holdings. Even the Bikar Cholum cemetery occupies nine acres of Huntoon land, on 115th Avenue N.

A School and a Club

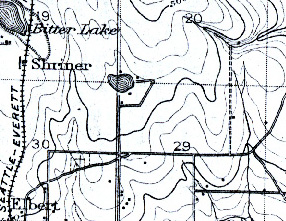

By 1910 the Seattle-Everett Interurban Railway was running through the area just west of the North Trunk Road (now Aurora N), with stops at Groveland, Bitter Lake, and Foy. Country Club Road (Greenwood Avenue N) to the east, also ran north and south through the Haller Lake area. Despite the relative ease by which people could now come and go, development in the area proved slow. It was mostly a neighborhood of farmhouses and summer cabins, but by 1921, it had enough residents to establish one of the Seattle area's first community clubs. And in 1919, the Lakeside Boys School (now Lakeside School) opened at N 145th Street.

But by 1930 most tracts were not even 25 percent filled. In the Overland Park Addition running along N 145th Street, which had recently been put on the real estate market, only 24 homes were present on 1,000 surveyed lots. Development around the lake itself, of course, was more established, with more than two-thirds of the lots occupied.

Chickens, Cows, Rabbits, Turkeys

Huntoon never realized the full economic potential of her land, which began with development in the 1950s. During her 11-year residency in Seattle, the Haller Lake population never exceeded 500. It would reach 1,000 in 1940. Urban Seattleites had little reason to move beyond city limits into an undeveloped area.

The landscape was dotted with chicken farms, dairy farms, and orchards. Open fields, including the site that became Northwest Memorial Hospital, provided grazing land for farm animals. Homeowners often kept pet geese, ducks, chickens, turkeys, and rabbits. Even today, some of the land around the lake is certified as a state wildlife sanctuary.

Although Huntoon never platted her holdings, much of the land surrounding hers was divided into plots of one, two-and-a-half, five, and 10 acres. Unlike earlier Seattle suburbs, such as Magnolia, Queen Anne, and Green Lake, whose developers envisioned residential neighborhoods built on small lots with little elbow room, Haller Lake was never intended as a bedroom suburb. By 1951, most of these large lots were still present. But change, and smaller lot sizes, were on the way.

The Age of the Shopping Mall

In 1950, the Northgate Mall, one of the country's first regional shopping centers, opened its doors and its parking lots within walking distance of Haller Lake, bringing new development to the community. Four years later, in 1954, the City of Seattle annexed the Greenwood District north of N 85th Street, extending city limits to N 145th Street, and bringing seven square miles of land and its residents under its municipal code. Haller Lake residents supported annexation because of the promise of storm sewers, sidewalks, and other amenities enjoyed by Seattleites.

Despite annexation to the city nearly a half century ago, Haller Lake still lacks much of the infrastructure necessary to sustain new growth. Rain run-off often fills Haller Lake causing flooding in nearby basements. Much of the community is still without sidewalks, and no curb currently exists to separate cars and pedestrians along the busy Aurora Avenue N.

Activists For the Community

I-5 and Aurora Avenue N provide quick access to jobs downtown, and N 130th Street provides a convenient connector route between these two corridors, but the price has been traffic, noise, and congestion. Activists in the community have long opposed continued growth in the area.

In 1963, when the freeway nosed its way through the eastern edges of the neighborhood, highway developers, at the insistence of community activists, constructed a noise barrier, as well as Northacres Park, north of 125th Street, providing playing fields and a wading pool for the community's youth. Activists successfully blocked a proposed garbage transfer station in the neighborhood in 1965, and twice, in the 1970s and 1980s blocked Metro's plan to build a bus barn on Aurora Avenue. The bus barn, a victim of "not in my backyard, you don't!" activism, was eventually built in the City of Shoreline.

Despite these victories, growth continues in Haller Lake. There are an increasing number of warehouse stores and parking lots being built where small businesses along Aurora once stood. Along with these changes come more noise and congestion.

Activism continues, nevertheless. Thornton Creek flows to the east and south of Haller Lake. The city and many volunteers are working to restore the creek to its natural state, including restoring spawning habitat for migrating salmon. In 2000, Haller Lake residents joined Maple Leaf and other North End groups in opposing the expansion of Northgate into its south parking lot. The historic South Branch of Thornton Creek had been buried in pipes when the shopping center was constructed in 1950. The expansion would have precluded forever "daylighting" the creek -- restoring it so that it would support spawning salmon. Eventually, the developers abandoned the expansion plans and offered the property for sale.

Work on daylighting parts of the creek has continued, and in 2002 a fish ladder with a series of cascading weirs was completed. This tripled the amount of good spawning habitat accessible to migrating salmon in the south branch of Thornton Creek. Still, a 2007 State of the Waters Report by Seattle Public Utilities found that the creek was polluted and that continuing environmental degradation results in about 79 percent of the coho entering the stream dying before they can spawn.