The Ravenna and Roosevelt neighborhoods of Seattle, also known as Ravenna-Bryant and Roosevelt-Fairview, extend north from the University of Washington, from Union Bay to Interstate 5 and Lake City Way NE. Ravenna originated before the university moved into the area and Roosevelt developed after the automobile. Both were heavily influenced by the university community and each reflects that in different ways.

Before the arrival of settlers from the United States, the principal feature of Ravenna and Roosevelt was the creek that drained Green Lake and emptied into Union Bay. The land was covered with tall stands of Douglas Fir hundreds of years old. Native Americans lived in a village on the western shore of Union Bay at about where the University of Washington Power Plant was later built. They lived in family groups in permanent cedar longhouses during the winter. Summers, the groups would scatter to fish, hunt, trap, and dig edible roots. The creek started relatively shallow and deepened to a steep ravine.

The earliest landowner was William N. Bell (1817-1887) who, in the name of his wife Sarah Ann (1815-1856), established ownership of the lower end of the creek. The property gained value in the mid 1880s when the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railroad was extended from Seattle up the western shore of Lake Washington. By 1887, ownership of the land changed hands several times until George and Oltilde Dorffel held title. That year they platted Ravenna Springs Park, linking the Italian seaport city with the sulfur spring along the creek. They set aside the steep ravine as a park because of its beauty and perhaps because the topography precluded use as building sites. The creek had been ignored by loggers and farmers and still possessed its old-growth timber. Ravenna became a stop on the new railroad.

The following year, William W. Beck, a Presbyterian minister from Kentucky, and his wife Louise purchased 400 acres on Union Bay. They developed the property around Ravenna station into town lots. Ten acres were set aside for the Seattle Female College which, by 1890, boasted 40 students studying music and art, five years before the University of Washington moved in nearby. The college folded following the Panic of 1893. Beck also opened the Ravenna Flouring Co., which he claimed was the only grist mill in King County.

Build a Park and They Will Come

The Becks fenced the ravine between what would become 15th Avenue NE and 20th Avenue NE and opened Ravenna Park. They imported exotic plants and built paths and picnic shelters. In 1891, David Denny's Rainier Power and Railway Co. completed a streetcar line from Seattle by way of a bridge across Portage Bay (the Latona Bridge crossed at the location of the present Interstate-5 bridge). The tracks went up 15th Avenue NE to the park, then followed the southern boundary to Ravenna. Ravenna Park became a popular destination for Seattle residents, who were willing to pay 25 cents apiece to visit it. Annual passes were $5.

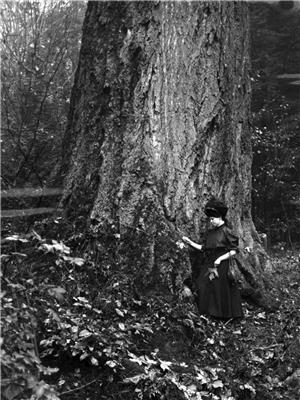

Ravenna Park’s most sublime attractions were its big trees. When the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was planned nearby at the University of Washington, in 1908, the Becks allowed local clubs to name the largest trees. The Becks called one Paderewsky after the Polish pianist who was a friend of Mrs. Beck. The tallest fir -- a spectacular giant that rose nearly 400 feet to about two-thirds the height of the Space Needle -- was named Robert E. Lee by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Mrs. Beck named the tree with the largest girth Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), the president who visited the park and whispered his approval.

The Roman Catholic Bishop of Nisqually for the Territory of Washington selected Ravenna for its cemetery in Seattle. Forty acres on a hillside was consecrated in 1889, making it ready to accept burials. In 1904 the land was officially platted as a cemetery. Caskets and mourners traveled by train to Ravenna Station on the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern.

Trees? What Trees?

The Becks had offered to sell Ravenna Park to the city of Seattle several times, but the city council balked at the $150,000 price tag. In 1911, the city condemned the land and a court set the price at $144,920. Once the park became city property, the great trees began to disappear. In 1913, the Seattle Federation of Women's Clubs complained to Park Superintendent J. W. Thompson that the Roosevelt Tree had been cut down. Thompson said that the tree was rotten and was a "threat to public safety" (Sherwood). The wood was sold as fuel to defray the cost of removal. In 1920, Thompson was pressured to resign for abuse of office and intoxication.

In 1926, the Seattle Parks Board contracted to have the last of the giants felled because they were "rotten at the heart and for safety reasons had to be removed" (The Seattle Times). Targeted for removal were the Robert E. Lee, the Paderewski, and the McDowell. This brought protests from the community and from former owner William Beck. Park engineer L. Glenn Hall assured the community that only dead trees would be felled. Hall promised to leave stumps at least 20 feet tall to avoid bare spots. Soon, all the great trees were gone.

In 1891, Seattle annexed the area around the University of Washington and Green Lake, including the Roosevelt District. The Town of Ravenna, an L shaped area north and east of 15th Avenue NE and NE 55th Street, passed out of existence in 1907 when Seattle annexed it as well. During those years, Seattle city engineers diverted Ravenna Creek from Green Lake into a sewer that discharged into Union Bay. The stream became a brook. Ravenna Boulevard was constructed between Green Lake and Ravenna Park along the stream, following a recommendation in the Olmsted Plan of 1903.

Developer Charles Cowan acquired the upper end of the Ravenna ravine, west of 15th Avenue NE, in 1906. He set aside eight acres there for Cowan Park and donated it to the city of Seattle the following year. The development of transportation for A-Y-P visitors sparked the development of northeast Seattle.

Roosevelt High School was an example of the rapid growth of the neighborhood. In 1920, the Seattle School Board proposed a $3 million building for the Ravenna area, but vocal opponents complained that it was "Too far out," "Too big," and "Too Expensive" (Seattle School Histories). The board had the support of two of Seattle daily newspapers, though, and construction of the building was ready for the 1922 school year. Within five years, the school had exceeded its capacity and 11 more classrooms were added.

Not In My Back Yard

Residents of Ravenna have always been fiercely resistant to changes in the environmental quality of the neighborhood. This is possibly because so many faculty and staff at the University of Washington made the area their home.

In 1948, the community battled the City Engineer over efforts to divert Ravenna Creek into sewers. In 1983, protests against the spraying of the pesticide carbaryl by the state Department of Agriculture to combat an infestation of gypsy moths resulted in a switch to a different compound. The alternative spray was successful. In 1991, the community blocked a city plan to dig up the park for a new sewer.

Roosevelt Remembered

When Theodore Roosevelt died in 1919, citizens showered the city with his memory. The new high school bore his name and 10th Avenue NE became Roosevelt Way NE. The area between Ravenna Boulevard and Lake City Way NE became the Roosevelt District after a naming contest sponsored by the Commercial Club in 1927. Roosevelt Way connected with Lake City Way NE (also called Bothell Road and Victory Way) and became part of the Pacific Highway between Mexico and Canada.

The construction of Interstate 5 in the early 1960s redefined the western boundary of the district. From 1919 to 1931, Ravenna Park was named Roosevelt Park, but residents lobbied the Parks Board to restore the original designation.

In 1911, 10th Avenue NE was an unpaved country road. In the 1920s, a thriving commercial district sprung up along Roosevelt Way NE as the automobile transformed America. On January 1, 1928, Sears, Roebuck & Co. opened its North Seattle store at NE 65th Street. The giant retailer closed that store in January 1980, and the building was turned into Roosevelt Square shopping arcade.

The growth in the University of Washington after 1950 meant that many faculty, staff, and students made their homes in the district. In 1945, there were 7,000 students. That number tripled over the next 15 years and almost doubled five years after that. That diverse cultural influence resulted at the end of the century in a "Metaphysical Belt ... including an institute of Chinese medicine, Ananda yoga and meditation, acupuncture, various types of massage, reflexology and other alternative disciplines. It also has three major esoteric bookstores that complement each other" (Seattle P-I).