Douglas Q. Barnett (1931-2019) was the founder of Black Arts/West and instrumental in the development of theater in Seattle's African American community during the 1960s. Black Arts/West opened on April 1, 1969, and was directed by Barnett until his resignation on July 31, 1973. This is Part 2 of his five-part history of Black Arts/West during his era and the flowering of African American theater and dance during those turbulent years. A complete list of the 32 plays produced during this period is included at the end of Part 5.

The Firehouse

The excitement and fervor of that first year with Central Area Motivation Program (CAMP) was tempered by the frustration of not having adequate rehearsal space for the drama component. The rear eastern section of the CAMP building was used for the dance department. We had obtained plans from Ruthanna Boris to build a "sprung floor" for the dancers. Being an old firehouse, it had a concrete floor, not good for the legs of dancers. We obtained a small grant and had the floor built along with a professional barre. The specifications were the same used at the New York City Ballet!

The drama unit was forced to perform in a space immediately inside the front door of the building. Evening rehearsals were hampered because of meetings being held upstairs. Oftimes we were told to quiet down or leave, despite the fact we were a part of CAMP's 15 component program. In reality we were not held in very high esteem, and many questioned the validity of CAMP having a performing arts unit. A question mark hovered over the program and while it was never publicly stated, it was made clear that we were on a short track to make good quickly, or else!

In Walked Bud

At that time there was a lot of student unrest at college campuses around the country, including the University of Washington. There were sit-ins and demonstrations almost daily, and one of our actors, Anthony D. Hill, (now a Professor in theater at Ohio State) was actively involved trying to get the drama department to revamp its all-white curriculum, and to hire an African American instructor.

With our recurring rehearsal space problems, he suggested that we go to the University of Washington and rehearse there. When it was mentioned that we had no authority and would be denied, he said words to the effect of: "We'll just take it, that's all. What are they going to do? Arrest us? We'll raise so much hell, they'll be afraid to arrest us!" So we loaded into our cars and proceeded to "Bogart" our way into one of the Theater Department rehearsal rooms.

Shortly after we began, the door opened and a man asked us what we were doing. When told that we were rehearsing our play, he asked upon whose authority. One of the actors replied, "Under the great God, Dumballah, whose wisdom is all powerful." The man whispered something under his breath, shook his head, turned to leave, and then said, "I lock up at nine, so you'll have to be out of here by then." We assured him it would be so and when he closed the door, we let out a roar! We continued to use the drama department rehearsal rooms periodically until obtaining our own space in 1969.

By this time I'd been educating myself in the theater. I had studied acting with Archie Smith of the Seattle Rep, and was also friends with Stephen Joyce, one of their lead actors. Between the two of them I'd seen most of the Rep's "classical continuum" of Sheridan, Ibsen, Chekhov, et al., and, with the exception of Shakespeare, I was bored to tears. They were static, talky, generational, and conflict was alluded to, but seldom seen.

But there was a white knight in my life and that was Joe Papp of the Public Theatre in New York. I loved what he was doing with free Shakespeare in the park and multi-racial casting. Theatrically speaking, Joseph Papp was my unadulterated hero. It was a personal goal of mine to do the same thing in Seattle, but it never came to fruition.

Straight! No Chaser!

A conscious decision was made to put together an acting troupe consisting entirely of black males. The idea was to confront Mighty Whitey with the myths and stereotypes of his own invention: the Black Stud, the 12-inch penis, the inferior intellect, the deflowering of the white woman, the unclean beast, the "gangsta" mentality, and the insatiable sex monster.

We were fortunate in finding people like Alexander Conley III, Randy Garrett, Robert Livingston, and A. D. Hill, who formed the core group of the New Group Theatre. They were bright, educated, articulate, and ticking time bombs on stage.

Days of Thunder

Most of the scripts we had access to were dated, so we developed our own improvisational. The scenario and characters would be plucked from local and national headlines, and the actors would improvise off of them. No individual or institution was safe. We satirized the Chicago 8 trial, the bumbling incompetence of the local Black Panther unit, Dr. Charles Odegaard of the University of Washington, Police Chief Frank Ramon, the attempted glorification of the Vietnam war, and local TV editorialist Lloyd E. Cooney, Coon, Coon, Cooney Coon, Coon, Coon, Cooney, Lloyd, Coon Cooney, Coon Coon, among others. Everything was taped. The best lines and situations from the improvs would be isolated. Then I would build the scene in terms of primary goal, clarification, bridging, and transitioning to the next scene. Three of our most successful shows came out of this process: Days of Thunder, Nights of Violence, Burn Baby, Burn, and Da Minstrel Show.

Burn was into its second week when Martin Luther King was assassinated on April 4, 1968. The community was inflamed and we were told by CAMP to cancel that night's performance. Riots broke out and it was decided due to the incendiary nature of the show that it be terminated.

Politics ruled. It was the first of many such Central Area Motivation Program edicts that intruded upon the development and integrity of what we were trying to accomplish. Our charge at CAMP was to reach unmotivated youth and get them involved and off the street. But it was like butting your head against the wall. No matter how many times you did it, it still hurt, and the result was the same.

A Change of Pace

We decided on another tack and visited schools in the area talking with teachers about their most motivated, bright students. Those that did take part were sharp and quickly progressed in both dance and theater. In time we were doing lecture demonstrations, and then full fledged performances, especially in dance. We choreographed whole dance numbers to current pop hits and invited kids in the community to see the performances free. And they came. Slowly at first, but they came.

Then the word got out that this was "cool." It was "hip." So the numbers increased. The inquiries increased. You'd see them out on the street, trying to do this move, or that one. Then they asked in. How much would it cost? We told them as much time and energy as you could put into it, because its going to be hard. They scoffed. It can't be THAT hard! But it was.

In time they learned the language. Stage right. Stage left. The barre. Downstage. "One, two, three, and four. Once again, one, two, three, and four ... "No, downstage left, not right. I don't want to see your shoes hitting the floor. Quickly now ..." And on it went. Some dropped out. Many stayed in. It came down to the old adage of what is best, the carrot or the stick. In our case the carrot won out. The stick would come later.

Enter: The San Francisco Mime Troupe

In November 1969 the San Francisco Mime Troupe came to town for a performance at the University of Washington. Their performance of The Minstrel Show was a scathing, satirical indictment of race relations and the military industrial complex. Several of the actors and myself followed the Mime Troupe as they performed university gigs at University of Oregon, Reed College, and Oregon State University. We hit it off well with the head honcho, R.G. Davis, and since we loved The Minstrel Show, he allowed us to use whatever material we desired if we wished to pursue our own production.

We did eventually, but most of the material was developed by us in the usual way. It was a very controversial production which drew a Black Students Union walkout when we performed it at the University of Washington They couldn't get past the blackface and left in the first minutes of the first act!

Seattle's First Black Film Festival

Another venture which was incorporated into our program was a Black Film Workshop for young teens. The idea came from an article in Negro Digest describing a program in New York called Mobilization For Youth run by Woodie King Jr. Like us, it was an anti-poverty program designed to keep unmotivated youth off the street and involved in meaningful activity that would stretch their minds, and incorporate the foundation for learning.

We managed to scrape together funds for a New York trip where I met Woodie King. We became fast friends and he agreed to come West with some of the workshop films if I could find money to start a similar workshop in Seattle. This was done with the help of Bill Dorsey, a KING-TV cameraman, and some of his friends at KING-TV. They smoothed the way for a meeting with Stimson Bullitt of the Seattle Foundation, and we received a grant of $2500 to purchase a number of Super 8 cameras and film stock. To launch the program we came up with the concept of a Black Film Festival -- the first such for Seattle.

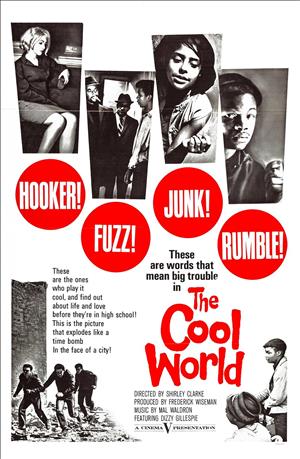

The festival was held in November 1968. Woodie brought along several of the workshop films, and we augmented them with some classic oldies like Nothing But A Man, The Cool World, and others. The KING-TV camera people instructed the kids and there was a high degree of excitement through the first four weeks.

But the fifth week, disaster struck. The CAMP firehouse was broken into and our dreams were dashed as most of the cameras were stolen from a locked storage container on the first floor. One camera remained, out on assignment with a student. This incident effectively closed the program because we had more than 10 students enrolled with not enough cameras to fill the void. It was a big disappointment and damaged our credibility as a steward of funding grants.

To go to Part 3, click "Next Feature," to see Part 1, click "Previous Feature"