The city of Kent, located 15 miles southeast of Seattle, was home to some of the earliest white settlers in King County, and was the first city in King County to incorporate outside of Seattle. Originally an agricultural community, it has since developed into an industrial center.

Early Human Habitation and the Oceola Mudflow

Thousands of years ago, the land now occupied by the City of Kent was oceanfront property. Elliott Bay extended far down the Duwamish Valley, at a depth of hundreds of feet. In approximately 3600 B.C.E., the top 2,000 feet of Mount Rainer slid off, sending .7 cubic miles of mud and rock throughout the White River Valley. This mudflow stopped near Auburn in a massive pile of debris.

The Osceola Mudflow changed the course of the White River, sending it north. Over the centuries, the river sluiced through the mud bump, filling the valley with alluvium. By the time the first white settlers arrived in the mid-1800s, the valley was filled with rich, arable land -- perfect for farming.

Native Americans had been fishing, hunting, and gathering berries in the valley and surrounding plateaus for years. Many Indians welcomed the pioneers, for the newcomers broadened their trading potential. But as more settlers arrived in the valley, the Indians’ access to the river and surrounding land diminished. Tensions flared.

Indian Wars

By 1855, treaties had been signed with Indian tribes throughout Puget Sound determining land rights, but the White River Indians were more reluctant to be moved than the Snoqualmie and Snohomish tribes to the north. Starting in the fall of 1855, some of the local Indians decided to fight back.

On October 27, 1855, an Indian ambush killed nine people, including women and children. A few children escaped and were helped towards Seattle by local natives who were sympathetic toward them. This began what became known as the Seattle Indian Wars.

Troops were brought into the area, and within a few months the Indians had retreated and the war was quickly over. A new treaty was written which provided the establishment of the Muckleshoot reservation, which is the only Indian reservation now within the boundaries of King County. The White River tribes collectively became known as the Muckleshoot tribe.

Back to the Valley

After the ruckus, settlers were slow in returning to the valley. In 1859, Thomas Alvord and his wife bought property along the river and set up a successful ranch and trading business. John Langston arrived in 1862 and opened up a general store. Also in 1862, James Jeremiah Crow eloped to the valley with his bride Emma, where they later raised 13 children.

Farmers again took to the land, raising crops of potatoes, onions, and other vegetables. Animal stock was brought in to pasture on untilled land. By the late 1870s, much of the valley had been cleared, and a new cash crop was cultivated -- hops, a bitter plant in the hemp family used to flavor beer.

The hops craze took the valley by storm. Cheap to produce, hops commanded a high price on the market due to a blight in Europe. Hop farms and hop kilns blossomed throughout the valley, making many farmers wealthy men. For 10 years hops were king, until aphids destroyed most of the crop in 1891. Nevertheless, hops were the catalyst that transformed transportation routes in the valley.

Rails and Travails

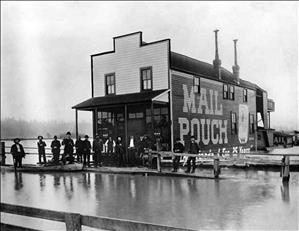

As soon as the first hop crop was picked in the early 1880s, farmers needed a way to get it to market. River travel was the most reliable transportation to and from Seattle. Flat-bottomed steamboats became popular, many of them mooring at Alvord’s Landing. Soon roads were built, and bridges spanned the river.

In 1883, work began on a rail line through the valley that connected up with the Northern Pacific, then owned by Henry Villard. But Villard had business troubles, and resigned before the line was completed. Pro-Tacoma, anti-Seattle interests acquired the Northern Pacific, and the branch line soon became known as the Orphan Road, due to its neglect.

After much legal wrangling, the line was brought into service, albeit poorly. King County riders complained, and the Northern Pacific again shut it down. It re-opened when the rail line was threatened with land grant revocation. It wasn’t until 1887, when the Northern Pacific moved its terminus from Tacoma to Seattle, that the Orphan Road became a reliable means of transportation in the valley.

The Hop Crop Stops

The railroad also gave Kent its name. Most folks had been calling the small community Titusville, after an early settler. In 1885, a general construction engineer for the Northern Pacific was quoted as saying, "We'll call this station Kent, after Kenty County, England where they raise nothing but hops."

In July 1888, John Alexander and Ida Guiberson filed the first plat. Other community members made additions over the next two years, and in 1890 citizens expressed a wish to incorporate. On May 28, 1890, the town of Kent became the first city in King County outside of Seattle to do so.

Kent was riding high, but the ruination of the hop industry in 1891 changed all that. Then, in 1893, a nationwide economic collapse made things even worse. Rich farmers became paupers practically overnight. Even Thomas Alvord was declared insolvent, and his ranch and belongings were sold at a public auction. Nevertheless, the town rode out its woes.

Milk and Money

Kent’s first big success in the post-hops era was Elbridge A. Stuart’s Pacific Coast Condensed Milk Company. After producing their first cases of condensed milk on September 6, 1899, the company later went on to success under the name Carnation Milk Company.

By the turn of the century, Kent had banks, schools, churches, stores, newspapers, and social organizations -- all the ingredients for a growing community. In 1902, interurban rail service came to town. Farmers received a break in 1906, when a major flood diverted the White River southwest through Pierce County. Before this, the White River merged with the Green River near Auburn, and both rivers caused havoc by flooding every year. Now, Kent farmers only had the Green River to contend with.

During this period, Kent farmers also played an important role in Seattle history. Upon bringing their produce into the city, the farmers had troubles with wholesale dealers who defrauded them and kept prices high. Because of this, Pike Place Market opened on August 17, 1907, so that growers could sell their fruits and vegetables directly to consumers.

Meet the Producer

During the first part of the twentieth century, Kent grew just as many farming communities did. In the 1920s, Kent became known as the “Lettuce Capital of the World.” Egg and dairy farming also became popular, and businesses like Smith Brothers Dairy and the Ponssen Brothers’ Kent Poultry Farm came into being.

First-generation Japanese farmers, the Issei, were able to lease farmland from American citizens. By 1920, the Issei in the Kent Valley supplied half the fresh milk consumed in Seattle, and more than 70 percent of the fruit and vegetables for Western Washington.

When the Great Depression struck, Kent suffered, but took things in stride. In 1934, the town held a lettuce festival, which drew more than 25,000 people to the community. Lettuce-related floats paraded through town, a lettuce queen was chosen, and 5,000 people got to eat the “world’s largest salad.” A good time was had by all.

The Good Times End

World War II changed the community. Japanese Americans, who had already witnessed growing discrimination in the 1930s, were forced to relocate due to Executive Order 9066, which ordered all Issei and Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans) to internment camps.

Between May 8 and May 11, 1942, entire families, some of whom had lived in the valley for more than 30 years, were placed on trains out of town. Since the Nissei were born on American soil, those with property were allowed to sell it or turn it over to the government for holding. After evacuation, the government redistributed 1,600 acres of farmland to other farmers.

Farming remained a top priority during the war, but with the removal of Japanese Americans and the loss of young men into battle, labor shortages arose. With women helping out in the defense industry, schoolchildren were enlisted to help out on the farms.

After the war was over, very few Japanese Americans returned to the valley, in part due to continued racial prejudice expressed against them by white residents, following Pearl Harbor. Meanwhile, changes in water management on the Green River brought changes to the landscape, but not in a way that farmers were expecting.

Dam Transformation

Damming the Green River high up in the mountains had been a goal for valley residents since the 1920s. Studies had been made before the war, but it wasn’t until 1950 that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers helped to convince Congress to adopt a plan to create a storage dam at Eagle Gorge.

Initially, valley farmers couldn’t have been happier, having had to deal with annual flooding for years. Construction of Howard A. Hanson dam was completed in 1962, and has prevented a major flood ever since. But instead of opening up land for farming, developers and industrial giants swooped in and began to transform the valley.

Adding to the changes was the creation of the Valley Freeway, which was given the green light in 1957. Interstate-5 on the western rim of the valley was completed in 1966. The City of Kent, seeing the changes on the horizon, began annexing as much land as possible in order to expand its tax base. The physical size of Kent grew from one square mile in 1953 to 12.7 square miles in 1960.

Fly Me to the Moon

The first major industry to move to Kent was the Boeing Aerospace Center, constructed in 1965. The Apollo Moon Buggie was built here in 1970, where lettuce had grown only a few years earlier. Other industries that followed were mostly warehouses or manufacturing plants, but by the 1980s, high-tech firms began to predominate.

In just a few years, Kent had transformed from an agricultural community to an industrial center. The large number of businesses added to Kent’s tax base. The City of Kent has been able to spend a sizable amount of money on their park system, making it one of the largest in the county. The city is also a regional leader in education and the arts.

In existence for more than 110 years, the city of Kent has seen many changes, from hop farming all the way to moon buggies. Even with all of the transformations that have occurred, fruit and vegetable stands can still be found on the backroads around the city. Smith Brothers Dairy still sells milk, and downtown Kent still has an old-world charm. At least for now.