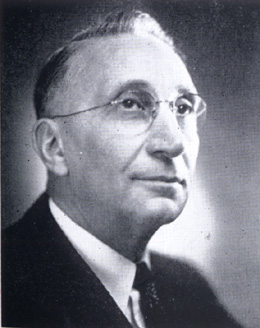

On January 15, 1954, Paul J. Raver (1894-1963) becomes superintendent of Seattle City Light. Under Raver, the utility will double the amount of power delivered, build Gorge High Dam, complete the Ross power plant, and improve the Diablo power plant.

Raver had been the head of the Bonneville Power Administration, having succeeded James D. "JD" Ross (1872-1939) in that position in 1939. City Light enjoyed a monopoly on electric power in Seattle since 1951 when the city purchased the Puget Sound Power & Light system. Raver continued the policy of promoting the use of electricity and of meeting new demand with more hydroelectric plants. Abundant power and low rates were seen as directly proportional to prosperity and the standard of living.

In 1957, City Light added seven floors to its headquarters at 3rd Avenue and Madison Street. The $2.1 million expansion allowed the consolidation of City Light and Water Department offices spread out over downtown.

Gorge High Dam was completed in 1961 to replace the timber structure completed in the 1920s. The project overcame daunting engineering challenges and a contractor who walked off the job.

Not all the obstacles to hydroelectric power were geologic. When City Light filed a claim on the site on the Pend Oreille River that would be Boundary Dam, local miners and the county public utilities district tried to block the project. The dispute ran through the governmental permitting process and then through the legal system all the way to the Supreme Court before construction could go forward in 1964.

As planning progressed for the 1962 Century 21 World's Fair, representatives from the American Institute of Architects, the American Institute of Planners, the Citizens Planning Council, and the Washington Environmental Council became concerned about the unsightliness of wires around the fair site. In November 1959, the City Council instructed the Superintendent of Lighting to prepare a plan to move unsightly wires that spanned the new freeway and hung over the World's Fair from poles to underground. Other wires were to be moved underground "consistent with revenues" ( Seattle).

Many of the 104,000 power poles in Seattle not only carried City Light wires, but the wires of the Puget Sound Power & Light system, which had been acquired by the city in 1951, as well as telephone wires. Electrical power for dense business districts was placed underground because poles would not support the wires needed.

But Raver and City Light were not in favor of undergrounding wires for beautification. Raver wrote, "City Light is at present on the defensive over an issue that needs more light and less heat. 'These unsightly wires must go' is the electrifying cry. Not only is the initial outlay great -- excessive where overhead service is already established, but maintaining trouble-free service also entails a greater expenditure of time in locating faults and making repairs than were the wires out in the open" (Seattle City Light News).

Late in 1962, Raver took ill, but continued to stay in touch with City Light from his bed at home. He died on April 6, 1963.

By the time of the World's Fair, the wires had disappeared around the Seattle Center, but the utility's resistance to undergrounding would be the cause for criticism by activists and elected officials. The opposition to Boundary Dam foreshadowed objections which eventually blocked the raising of Ross Dam.