The Puget Sound region used to be known as the Mediterranean of the Pacific, a place as balmy as a Greek island, if also rainy. But other weathers, severe and historic, have challenged the Mediterranean image. During the past 150 years, the "Big Winter" of 1861-1862, the "Big Snow" of 1881, the big and heavy snow of 1916 (which collapsed the dome of Seattle's St. James cathedral), not to mention various freezes, gales, and mud events have every few years blasted away the general mildness and excited the community.

Snow Is a Page

"A fresh snowfall brings a subtle change to the music of the woods ... Now all sounds are muted, as if nature stands in awe of the great changes it has brought to the land. This is a time for the nature-lover to read the diary of the forest, for the snow is a page on which each passing animal inscribes its message."

--Caption of a Puget Sound snowscape photographed in 1963 by Josef Scaylea

Our region is usually mild, but as J. Willis Sayre notes in his 1936 book, This City of Ours: "Seattle has been visited by a gale so strong that it blew seven railway cars off a trestle into the bay, has had a snowfall six and a third feet deep, has seen a winter temperature of four degrees below zero ..."

In 1949, Meteorologist Lawrence C. Fisher published a testament of Puget Sound's usual mildness. The 38 year veteran of the Weather Service served up a warm cocoa of statistics for his Seattle Times readers.

"Based on 56 winters of official records (our) annual winter snowfall is but 11.2 inches. This is less snow than for any place eastward across the continent of the same parallel of latitude ... Six winters in the 56 recorded have had no measurable snowfall, only traces ... In the 26 winters since the 16-inch fall of Feb. 14, 1923 the average winter snow has been only 6.9 inches."

Had he wished to join sentiment to his statistics, the weather forecaster might have also listed the seven years Seattle had a white Christmas in the 38 years he worked for the Weather Service -- in 1909, 1911, 1915, 1916, 1933, 1937, and 1946. Fisher did not fail to note the two big snows in the 56 winters since the Service began in Seattle. "Some of the deeper snows have begun in the latter part of January and reached their greatest depth in the early part of February, notably those of 1893 and 1916."

Pioneer Weather Diaries

It is certainly easy to imagine the first settlers joyfully measuring their drifts and accumulations. Without a Weather Service -- it was first established here in 1893 -- keeping a weather diary was almost a commonplace. It also made survival sense in a then still remote community on the wild edge of who knew what.

Later when the patterns of Puget Sound weather became familiar as exceedingly temperate, these dairies were continued as one of the delights of leisure. With hardly any media to distract them, dilettante meteorologists might twice daily record in their journals with terse and/or picturesque prose what is still our mainstay of small talk -- the weather. Like joining the toast at a neighbor's wedding with a single small glass of sweet wine, a snowfall of six or eight inches will not upset sobriety nor make one slip or swoon.

Mild for a While: The First Settlers

White settlers' first winter in Seattle -- 1851-52 -- was mercifully mild, but their second -- 1852-53 -- was unmercifully cold. Supplies dwindled as winter storms kept sailing vessels away. The settlers lost their last barrel of salted pork to a high tide and early ran out of flour. Besides what they could gather from the beach, they lived on wapatoes, small red potatoes grown by Indians in the Green River valley.

When at last a sailing ship arrived in Elliott Bay at 2 a.m. with supplies, especially flour, everyone was awakened including the children. "Quick biscuits" were baked and eaten immediately. It was the first bread the founding families had had in months and according to founding father Arthur Denny, "demonstrated the fact that some substantial life-supporting food can always be obtained on Puget Sound, though it is hard for a civilized man to live without bread."

The Cold Winter of 1861-1862

The coldest day dropped on Seattle during what pioneers unanimously called the "big winter" of 1861-1862. In his Pioneer Days on Puget Sound, Denny writes that he "carefully observed my thermometer and the lowest point reached by my observation was two degrees below zero." Feed was exhausted and across the Territory there was "a great and general destruction of live stock."

Through the "big winter" of 1861-62 the snow lay on the ground for three months. There were six inches of it on top of Lake Union and six inches of ice below it.

Whistling in the Icy Wind: the 1870s

Early in 1875 (on January 19), Lake Union froze over again and the Duwamish River froze over again as well. When the river ice broke up, strong winds drove it into Elliott Bay and onto the central waterfront where it so clogged the wharves that small steamboats could not get through.

The following November 16, a six hour gale scattered the pieces of three waterfront warehouses across the village, which raked off fences, chimneys, and trees. The 1875 wind rivals the October 12, 1962, Columbus Day storm as the worst to hit us. The gale wrenched loose two of the four columns on the Territorial University building on Denny's knoll, in downtown Seattle.

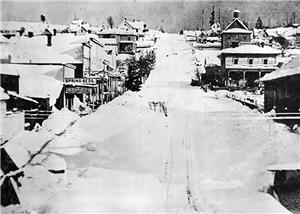

The "Big Snow" of January 1880 was well described by locals, and there are at least six surviving photographs. Pioneer accounts corroborate Sayre's claim: "The five-day snowfall drifted in places to over six feet." That makes the 1880 "Big Snow" still our biggest snow 122 years later (2002). Snow began falling on January 5, 1880, immediately following Territorial Governor Elisha Ferry's State of the Territory message assuring the world that "ice and snow are almost unknown in Washington Territory."

Two years later, on February 9, 1882, a gale blew six cattle cars and a caboose into Elliott Bay.

During February 1884, Lake Union and all rivers flowing into Puget Sound froze over. Boating on the tributaries was shut down except for the sternwheeler W.K. Merwin that backed its way down the Snohomish River to salt water by cracking the ice with its paddle wheel. A short snow of two inches covered Seattle on the February 8, and held. A thaw began on February 15, deceptively, for three days later 18 inches of fresh wet snow fell on the community of about 8,000 citizens.

The Big Snow of 1893

By one newspaper account the big snow of 1893 began on January 27 and kept up almost steadily dropping 45 inches before it stopped on the February 8, 1893. On February 3, a reading of 5 degrees below zero was claimed at Woodland Park on Phinney Ridge, while down the hill on Green Lake the ice was six inches thick.

In his book Seattle, long-time Post-Intelligencer contributor Nard Jones notes of the 1893 snow and cold that "it frightened a good many Seattleites nearly to death; they thought the end of the world was on its way and not in accordance with the Bible." The following autumn the world seemed to end again for the religious and secular alike with the great economic panic of 1893. Those "last days" held until 1897.

The first snows of 1896 were early. A November accumulation of 20.5 inches set a November record.

Twentieth Century Weather

Seven years later, in March 1903, 8.6 inches fell. That too was a record at the time for that month.

In January 1907, this boom town of nearly 200,000 citizens had grown too big too fast for its services. The single foot of snow and accompanying cold that blew in that month filled our hotels with those citizens who could afford such plush relief but could not, nevertheless, purchase fuel for their homes. Others resorted to burning whatever was available -- old furniture, boxes, fences.

On Christmas Day, 1909, the afternoon paper noted "When the town woke up this morning the hills and dales were covered with a mantle of snow that brought to the city that dearly beloved white Christmas. All those who dreamed they were back in New England or in the Middle Northwest ought to telephone the weatherman the joyous greetings of the holiday season." That afternoon in West Seattle, a teenage boy exploring the snowbound woods near Charlestown Street and 37th Avenue SW was surrounded by barking coyotes. During the process of running home, he somehow managed to count the pack. There were 10 of them.

The Big Snow of 1916

When the big snow of 1916 began to fall on a cold Monday on January 31, 1916, there may have been more cameras than shovels in the hands of amateurs. The flurry of snapshots of our second greatest snowstorm illustrate snow-stopped streetcars, closed schools, closed libraries, closed theaters, closed bridges, a clogged waterfront, collapsed roofs, and -- most sensationally -- the great dome of St. James Cathedral, which landed in a heap in the nave and choir of the sanctuary. (There were no injuries to persons.)

The unusually cold January already had 23 inches of snow on the ground when, on the last day of the month, it began to fall relentlessly. Between 5 p.m. on Tuesday, February 1 and 5 p.m. on Wednesday, February 2, 21.5 inches accumulated in the Central Business District at the Weather Bureau in the Hoge Building. This remains (in 2002) a record -- our largest 24-hour pile.

The 1916 snow was a wet snow, and it came to a foul end -- a mayhem of mud that mutilated bridges and carried away homes.

Depression Skaters and Wartime Kidders

Although not regular, a Green Lake freeze is considerably more common than one on Lake Union. In both February 1929 and January 1930, the lesser (Green) lake froze over, to the joy of skaters who scrounged for clamp-on skates. Many skated past midnight. For warmth they visited the bonfires set in trashcans on the ice.

On Friday, January 15, 1943, snow began falling in Seattle, accumulating to a foot in depth, but what was obvious to residents could not be reported in the media. Wartime restrictions on information prohibited weather reports. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer had some fun with the regulations: "The thermometer changed its position more than somewhat Friday night and a lot of restricted military information fell in the streets of Seattle and vicinity early yesterday morning..." Stores and schools closed and so did many of the city's wartime industries.

Freezing in the Fifties

With a mean temperature of 28.7 degrees, January 1950 was colder than January 1916. On Friday January 13, a blizzard blasted in from the ocean. It continued through the night and into Saturday. The temperature dropped to 11 degrees. High winds lifted the waters of Elliott Bay onto the waterfront and frozen salt water instantly stuck to anything it splashed.

On Wednesday, February 1, 1950, a Seattle Times reporter noted "Last month apparently was designed to make the old settlers forget all about the "big winters of 1916 and 1893." Supervising district forecaster Tom Jermin consoled "We should remember that this is only the third extremely cold winter in 60 years." As in 1916 so in 1950: Cold air from British Columbia embraced a wet low-pressure storm from the coast with extreme results.

The big-freeze of mid-November 1955 killed thousands of trees and shrubs hereabouts, and many homeowners listed their losses the following year as tax deductions. The first snow came unannounced in the early afternoon of the November 17, 1955. First locking arms and then fenders, workers rushed home, creating an unprecedented blending of bumpers. More than 1,000 vehicles were involved in 441 reported accidents. Included in the statistics were two accidents involving six cars. The number of two- and three-car collisions were too numerous to take special note of.

Catastrophic Winds

On October 12, 1962, Columbus Day, a windstorm ravaged the Puget Sound region in what the National Weather service later designated as Washington's worst weather disaster of the twentieth century. Forty-seven people were killed between Vancouver B.C. and San Francisco.

Wind measuring devices measured gusts of 150 miles per hour early in the storm before power outages disabled the instruments.

Snow in July Followed by Snow in January

A kinder and more gentle snow was the artificial sort that befell Seattle on July 28, 1964. On that day Seattle witnessed the First Annual Pacific Northwest Snowball Fight between the disk jockeys of KVI and the chorus line performers in the Opera House production of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to The Forum. This snow-battle was held at the northeast corner of the Center on the odd lawn there that undulated with grassy mounds. Later the offices and studios of KCTS TV were built over it. Of course the snow was machine-made and the public was invited not to lob snowballs but to "observe."

Through the autumn of 1964 and into the first week of January, Seattle was rinsed repeatedly by alternating snowfall and rainfall. On January 6, 1965, a Times writer predicted "Years from now they will be telling tales about the past 27 days or so as the winter of the big snow here." Well they have not. The snow of 1964-1965 was like a prizefighter with a jab but no hook. It was not a knockout big one. There was too much rain.

Hill-Arrest: the Queen Anne Situation

Following the snow of January 5, 1967, police clerks were battered with calls imploring "How do I get up on Queen Anne Hill?" Police erected barricades on Queen Anne Hill, although residents kept sneaking around them, sometimes to their own peril. One dim but desperate caller asked "I have to get to work, will you come and get me?"

The So-so Snow of 1969

Somewhat timidly we may wish to add to the list of big snows the snow of 1969. It began on a Tuesday -- the last day of 1968 -- and repeatedly fell on Seattle through January. On January 24, Seattle Times hometown humorist John J. Reddin complained "This has to be some of Seattle's worst weather. Last summer was miserable, fall was among the wettest and now a freezing winter with snow and still more snow and it's only January." Three days later snow fell again. Seattle schools were closed for the first time in 19 years -- that is, since 1950.

Seattle Times humorist Byron Fish had fun with our snow, even the big ones. During the 1969 dumping, Fish introduced an essay he titled "Equipment Key to Snow Driving" with the maxim that "Nothing stops a snowstorm or dries a street like jacking up a car and putting on chains." In his test of different kinds of tires, with and without chains, every car winds up crashing into something. It seemed to be their purpose. Fish concludes, "We discovered that whatever the wheels are wearing, we learn where we are going after we arrive."

In another 1969 snow story Fish reports on his long-distance telephone call to Nome, Alaska, and how his friend there felt deeply for Fish in his plight of having to walk three blocks through the snow for groceries.

Visit the Captivating Queen Anne Hill

As a hilly town with micro-climates, even our lesser snows provide a low stage for slapstick humor -- gags like driving into ditches and slipping while shoveling. Our little wet snows can transform both a street and sidewalk into a runway of banana peels. One of the city's earliest cold and snow snaps hit and held through most of November 1985.

That fall, the writer Jean Sherrard and his wife Karen, a language teacher, invited a French friend to visit and stay with them in their home atop Queen Anne Hill. Soon after the friend arrived, our Mediterranean climate turned Arctic. When their friend returned to Paris in late November, the Seattle impressions she carried with her were narrowly circumscribed by the snowbound summit of our towering hill, where she spent her visit, all of it. While not fair this is still funny.

The biggest weather event of 1990 was not wind but wind added to human error: On November 25, 1990, after a week of high winds and rain, the 50-year old Lake Washington floating bridge, which was under repair, went to pieces and plunged into Lake Washington. The hatchways into the concrete pontoon air pockets had been left open, allowing water to enter.

Another wind disaster occurred on January 20, 1993, when an Inaugural Day storm with winds topping 94 m.p.h. ravaged Puget Sound. Six people lost their lives.

The Not-So-Big Snow of 1996

On Friday morning, December 27, 1996, a foot of snow fell on commuters. It closed the passes and cut into the traditional post-Christmas exhilaration of bargain shopping. However, the 1996 snow also put a stop to returns. It increased video rentals tremendously, a point that offered little consolation to the Blockbuster store in the Crossroads Shopping Center. Its roof fell in.

In fact the most serious injury was to roofs -- dozens collapsed under the wet snow including nearly all the sheds at the Edmonds marina. Three hundred boats sank. One foot of ordinary wet Seattle snow accumulated on the roof on an ordinary Seattle bungalow can weight two tons.

Near Misses

Many historic Northwest snowstorms have barely brushed King County. For instance on January 9, 1980, at 4 a.m. eight inches of fresh snow was measured at the Seattle-Tacoma airport, while a few storm miles south drifts as high as 14 feet were reported on the Columbia River Gorge near Multnomah Falls. In a case of "how did they ever find them?" an Amtrak Train rescued three stranded drivers.

On February 23, 1994, the Weather Service offered a forecast for Seattle that was familiar and comfortable. "Occasional showers tonight. Decreasing showers tomorrow with brief partial clearing, then increasing clouds in the afternoon. Highs upper 40s; lows: upper 30s." For the "mountain areas" the federal forecasters predicted "Snow showers tonight. Snow showers decreasing tomorrow." What fell was a national record. From Wednesday February 23, 1994 into Thursday February 24, 70 inches of fresh snow accumulated in 24 hours on Mt. Rainier at Paradise.

On Queen Anne Hill, it rained.