Amos Brown was a prominent early citizen of Seattle. He was a pioneering lumberman in the Puget Sound region beginning in the 1850s and had substantial real estate holdings in present downtown Seattle and in several counties along Puget Sound. Amos Brown built a cottage for Princess Angeline, the daughter of Chief Seattle, and in other ways was kind to her. He served as a member of the Seattle City Council, and was remembered as an "honored pioneer of the city." His son Alson Brown became a lawyer, and used his inherited wealth to develop an experimental farm in the Nisqually Delta northeast of Olympia. The 2,300-acre farm thrived from 1904 to 1919, and was considered a model of efficiency.

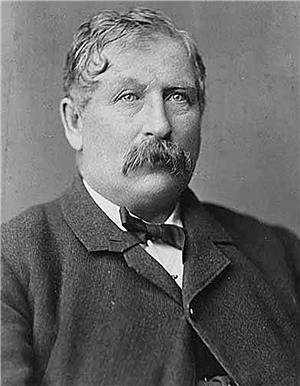

Amos Brown

A native of New Hampshire, Brown was of English and Scotch ancestry. His father was a prominent lumber manufacturer with extensive mills on the Merrimac River, in which Amos started working at the age of 10. Although his formal education was limited, his practical skills and management experience gained through the years provided a valuable foundation. Brown left home at age 21 (in 1854).

Four years later, he set out for the Northwest, tempted by the prospect of gold in Victoria. Leaving the Fraser mines disappointed, he settled in Port Gamble, on Washington's Kitsap Peninsula, and he resumed his trade running a logging camp. It was not long before he had bought an interest in logging teams and secured contracts to deliver timber to milling companies.

During this period (the late 1850s), Amos Brown had purchased land, sight unseen, in downtown Seattle on what is now Spring Street between 2nd Avenue and the waterfront. This real estate would provide the basis for his subsequent wealth.

He first visited Seattle in 1861 and in 1863 built the old Occidental Hotel in partnership with John Condon and M. R. Maddocks. In 1867, Brown settled in Seattle and was partner in a highly successful lumber business in Olympia. An 1880 story in The Washington Standard gives an account of a floating hotel Brown built for workers in his logging camps. The 24- by 36-foot, one story building was constructed on a float of logs.

He sold his interest in the business in 1882 and retired to manage and develop his considerable real estate holdings in Seattle and elsewhere.

Amos Brown died unexpectedly in 1899 (he was in his late 60s). Upon his death, he was honored as a founding father. Nearly a thousand mourners thronged the family home to pay their respects.

Friends recalled him as a generous man who encouraged his workers to contribute to the newly formed sanitary commission, and who raised money for the relief of Civil War soldiers all over the country. Among his contributions, he furnished the timber spars that helped the Puritan, Mayflower, and other racing yachts to defend the American Cup against England.

Alson Lennon Brown

A native of Seattle, Alson Brown was Amos Brown's son. Trained as a lawyer at the University of Oregon and a member of the Washington Bar Association, he practiced as an attorney and was involved in the insurance business as well. The entity formed to develop and liquidate his father's substantial holdings was listed as Amos Brown Estate, Inc., with Alson Brown cited as president.

It is likely that Alson Brown used at least part of his inherited wealth to embark on an ambitious development project outside Seattle. From 1904 through 1919, Alson purchased 2,300 acres of land between the Nisqually River and McAllister Creek in the Nisqually Delta on Puget Sound northeast of Olympia, diked and drained much of the salt marsh, and established a farm. Designed by Brown, the farm was a sort of experiment in modern farming. He used all the latest methods and equipment, hiring a year round crew. Ten years after he started, the farm was completely self-sustaining.

The farm production fed the crew and Brown provided housing by taking room and board out of the worker's pay. In addition to raising crops, the facility produced a wide variety of farm products, including dairy and poultry. The output of the farm was significant enough to have a box factory built on the farm for packaging. The large-scale farm distributed its products to the growing Puget Sound region. The farm was considered a model of efficiency and unique to the Puget Sound region as a volume producer of a wide variety of products.

Brown's fortunes turned for the worse at the onset of World War I. Unable to meet his debts, he lost the farm to creditors. The property was acquired by Robert P. Oldham after the stock market crash of 1929. Ownership later passed on to Bruce W. Pickering, who sold the tract in 1974 to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which established the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge on the site of the former Brown Farm. In 2016 the refuge was renamed the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge to honor Nisqually tribal leader, and founder and longtime head of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, Billy Frank Jr. (1931-2014).

In 1922, Alson Brown and his wife moved to Kent in south King County, where she died in 1938. Alson Brown died in Caliente, California on June 29, 1942. He had been living there for just a year and a half.