On January 14, 1971, the Washington Supreme Court decides the case of three protestors charged with unlawful assembly during a March 29, 1968, sit-in at Franklin High School. The Court reverses the decision of Superior Court Judge Solie Ringold, who declared the unlawful assembly law unconstitutional, and reinstates the charges against Larry Gossett, Aaron Dixon, and Carl Miller. However, the prosecutor decides not to try the case again.

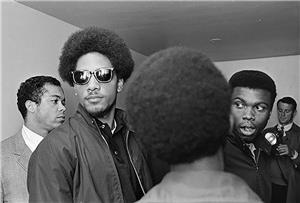

Gossett, Dixon, and Miller were convicted of unlawful assembly in Justice Court (a previous term referring to the District Court, or at times to the Municipal Court) and sentenced to six months in jail. They appealed to Superior Court where, under the procedures in effect at the time, they were entitled to a new trial. The three defendants were among a large group of high school and college students who occupied the Franklin High principal's office on March 29, 1968, to protest the suspension of two African American students. The jury in the Justice Court acquitted two other protestors.

Represented by a team of American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) lawyers, including Christopher Young, Andrew Young, Michael Rosen, and Ronald Meltzer, the defendants argued that the unlawful assembly statute was unconstitutional. The statute made it illegal for three or more persons to assemble with intent to "carry out any purpose in such manner as to disturb the public peace" and stated that if the assembly attempted or threatened "any act tending toward a breach of the peace," "every person participating therein by his presence" was guilty of the offense (Former RCW 9.27.060).

Judge Ringold, a former president of the Washington ACLU chapter, ruled that the statute was unconstitutional because it allowed conviction for acts of free speech and assembly permitted by the constitution, placed too much discretionary power in the hands of law enforcement, and permitted conviction for being present at unlawful acts in which one did not participate. The judge dismissed the charges.

In its decision, the Supreme Court reversed Judge Ringold and declared the unlawful assembly statute constitutional. The Court stated that the terms breach or disturbance of the peace had been used in the law for centuries and were not unconstitutionally vague or uncertain, but clear and understandable. The Court ruled that prohibiting disturbance of the peace did not deny freedom of speech or peaceable assembly. However, the court did make clear that a person who was merely present, but did not commit or intend to commit any of the prohibited acts, could not be convicted. The Court remanded the case for the defendants to be tried on the charges in Superior Court.

However, on remand the prosecution declined to prosecute again, and the case was over, three years after the sit-in and arrests. In 1975, the unlawful assembly statute was repealed, and replaced with a somewhat narrower law making one guilty of failure to disperse if he or she congregates with a group of three or more within which there are acts creating a substantial risk of injury, and does not disperse when ordered to do so by a law enforcement officer.