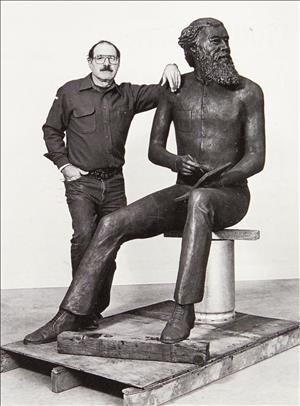

Sculptor Phillip Levine's work can be viewed all over the Northwest. In Western Washington alone, he has 30 sculptures that stand in public places, including Dancer with Flat Hat at the University of Washington and Walking with Logs on the hill facing the West Seattle Freeway. Beginning work in the 1960s, when the trend in art was abstraction, Levine concentrated on representational figures that have withstood the test of time. This biography of Phillip Levine is reprinted from Deloris Tarzan Ament's Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

A Very Visible Artist

Eighteen public commissions and 20 additional private commissions that stand in public places have made Phillip Levine's work among the most visible public art in the Northwest. In addition, he has been an influential teacher, instructing students in sculpture, drawing, and design at eight schools and universities.

Despite the impression his works make in the Northwest landscape, his roots are in the Midwest. He was born in Chicago on March 1, 1931, the second child of Belle Levin and Max Levine. His sister, Sandra, was four years older. His father was a partner in a ladies' ready-to-wear store.

At the beginning of the Great Depression, Max Levine's business failed and the family became part of the great internal migration that took place as people sought work. They first moved to Green Bay, Wisconsin, when Phillip was in kindergarten. By the time Phillip was eight, they had moved to Denver, where they lived with his mother's parents and three brothers for two years while Max Levine established himself as a salesman of tobacco, candy, gum, and sundries.

Pre-Med Student

Levine graduated from high school in Denver in 1948. He and Sandra were the first from either side of the family to attend college. Phillip entered the University of Colorado as a pre-med student. He was not happy with the curriculum. In the spring of his sophomore year, in lieu of science classes, he elected courses in three-dimensional design, philosophy, and Shakespeare -- subjects more congenial to his turn of mind.

"When I went back for my junior year, I took an art class," he said. "The idea of working with my hands was basic to my entire being. By the end of that year, I wanted to quit school and be an artist" (Levine Interview). Instead of quitting -- a decision that would have been incomprehensible to his family -- he stuck it out to graduate in January 1953, with a Bachelor of Arts degree.

New York

He did not yet conceive of a career as a sculptor; indeed, he had taken only one sculpture course. When he left for New York in 1954, it was as a painter. For the next few years, he took intermittent classes at the New School for Social Research, studying subjects as far ranging as Buddhism, Italian, ukiyo-e printmaking, and the poetry of Robert Herrick, while he worked at an ad agency doing paste-ups to ready art for the camera. "From my study of the history of art it seemed as if everything had already been done," he recalled, "so why bother?" (Levine Interview).

In 1956, during a stop-off in Denver on his way to Mexico, he attended a lecture, where he met Rachael Ann Hesselholt. Rachael, the daughter of an immigrant Danish father and a mother with Midwest roots, had grown up on a small farm in southern Idaho. She graduated from Colorado State University and had become an assistant nutritionist in a longitudinal growth study -- The Child Research Council.

Before marrying Levine in February 1957, Rachael converted to Judaism. The couple lived on Manhattan's Lower East Side, where Levine shared a studio with two other artists and Rachael could walk to her work as a dietitian at Beth Israel Hospital. Their first son, Joshua, was born at Beth Israel in June 1958. In December 1959 and in January 1962, respectively, sons Aaron and Jacob were born in Seattle. (Jacob became a flight instructor, and was killed in 1987, at the age of 24, when his plane crashed in the mountains near Albuquerque.)

He Begins to Sculpt

Levine moved his family moved to Eugene, Oregon, in the fall of 1958. He had begun to sculpt, and wanted to study for a Master of Fine Arts degree to improve his skills, and to qualify to teach. He chose the University of Oregon because its catalog listed sculpture as a separate category in the School of Art, indicating a depth and degree of emphasis he found lacking in some other universities.

Moves to Seattle

He was one of two graduate students in sculpture studying under Jan Zach. He stayed for only one quarter before moving to Seattle to enroll in the University of Washington. From the spring of 1958 to the spring of 1961, he studied with Everett DuPen and ceramicist Robert Sperry. He worked as a teaching assistant in drawing and design. During that time, he got a job with commercial artist and noted watercolorist Harry Bonath, doing paste-ups, as he had done in New York. He received a Master of Fine Arts degree in sculpture in 1961.

An Artist Teaching Art

In 1962 and 1963, he was a teaching assistant at the Burnley School of Commercial Art. In the same two years, a few blocks away from Burnley, he began his own school, the Phoenix School of Art, at 916 East Pike Street, near the Comet Tavern, in a building that formerly had been an auto paint store. The Phoenix School lasted for two years, with faculty members such as Patti Warashina, who taught ceramics classes. Her work was of particular interest to Levine, since he had done his master's thesis on polychrome stoneware sculpture.

"It wasn't just a way of making a living," he said of the school in retrospect, "but it was exciting. I did the usual thing for an artist of doing whatever it took to stay alive and support my family." Rachael became an instructor in early childhood and parent education at Seattle Central Community College, a position she held for 23 years. They lived in public housing at Rainier Vista for the first five years they were in Seattle. In the late 1960s, they bought a house in Burien near an industrial area convenient for Levine's work in metal.

Coming from a third-floor studio in New York, he was overwhelmed by the Northwest landscape, and by the Northwest seasons, dramatically different in their wet softness from the hard weather common in both Colorado and New York. He began to produce some landscape drawings. But Northwest light, which was a strong inspiration in the work of many Northwest painters, was not a key factor for Levine. Afflicted with a mild case of color blindness, he says, "I was never a colorist."

Pouring Metal

His career took a decisive turn in the mid-1960s, when he decided to explore bronze sculpture. "No one knew anything about bronze sculpture at the time. There was no art foundry in or near Seattle." He took a casting to William Stewart, who operated a commercial sand casting operation on Eastlake Avenue. He and sculptor Ray Jensen, who also took casting work to Stewart, were obliged to burn out their own molds before proceeding, since Stewart was not equipped with a furnace. "It was like an epiphany to work pouring metal," Levine said (Levine Interview). He was hooked.

Concentrating on the Figure

From the beginning, he was engrossed with the figure. "All my life I had heard 'The figure is dead.' But I was always drawn to it" (Levine Interview). The fact that it was, for a Jewish artist, forbidden territory may have been a factor for Levine, an intellectual rebel. Jewish tradition forbids the depiction of the human form as a guard against idolatry. The prohibition stems from earliest Biblical teachings, reinforced during the Roman occupation of Judea, when the emperor of Rome, believing himself divine, had his own image moved into the Jewish temple in a sacrilege repugnant to Jews.

Levine's interest in the figure had been jump-started shortly after he moved to New York, when he saw an exhibition at the World House Gallery by Giacomo Manzu (1908-1991), whom he counts as "one of the great sculptors of all time." Manzu, a celebrated Italian artist, extrapolated the Italian figurative tradition to bring a sleek modern look to the forms of dancers and clerics.

Levine also was impressed with Edgar Degas's sculpture, displayed on a balcony of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He was particularly struck by the figure of a young bronze dancer wearing a tutu made of fabric rather than metal.

"I wanted to learn to do the figure well," he said. It was a courageous choice. Artists making headlines in the 1960s were those who had turned from representation to abstract expressionism, with bravado brushwork on super-size canvases. Artists who pursued representation, particularly the figure, were at best ignored; at worst, scorned and subjected to ridicule.

The shortage of serious critical attention paid to Levine's work in ensuing decades is attributable in part to the "unfashionable" nature of his subjects. Yet thanks to that focus on the human form, his work has escaped the dated look of much work done in the 1960s. The figure is timeless.

Sometimes he has rendered the form realistically. More often he has played with it, exaggerating or minimizing features, lengthening legs, or adding machine-like elements as metaphors. He has become particularly adept at the depiction of emotional states through body language, such as the ecstasy of a dancer in motion.

Playing with Balance

His favorite theme, however, is the ambiguity of balance. "I like creating figures who appear to have a tenuous balance because it creates a slight sense of discomfort, of 'Can they do it?'" Sometimes the answer appears to be both yes and no, as in Quest, a visual metaphor for the transformational power of pursuing a dream. A sequence of five male figures slightly less than a foot high are attached to a 3-foot plank of polished wood. The first, remarkable for having coil springs as lower legs between the knee and ankle, appears to have sighted something overhead. The second figure crouches, elbows thrown back in balance. The central figure springs, coil legs pushing his arched torso up and back. In the fourth position, he is headless, the leg coils fully extended from feet sprung up onto tiptoe, arms rigid against the body. The hands splay out as if pushing off from space. In the final position, the body has snapped free, disappeared into space, leaving behind only the feet, still on tiptoe under broken springs. Quest is a maquette for a full-size piece, renamed Leap when it was rendered in figures 7 feet high, which rise in succession up the steps of the Spokane Veterans Arena.

Art in Public View

Perhaps more than any other sculptor of his time, Levine has been awarded commissions for public places in the Northwest. He has more than 30 publicly and privately owned sculptures in public places in western Washington, half a dozen more in eastern Washington, four in California, and several in Oregon, in addition to his pieces in major private collections including those of King Hassan of Morocco, the mayor of Chongqing, China, and the prime minister of Japan. His corporate commissions include pieces for Shell Oil, Security Pacific Bank, Safeco, Pacific Northwest Bell, and the Martin Selig Corporation.

Dancer with Flat Hat

His most visible and arguably his best-known public sculpture is the slightly larger than life-size Dancer with Flat Hat, which stands outside the Henry Art Gallery on the University of Washington campus. Levine completed the Dancer in 1971, for display on campus in a show of Art in Public Places. It was purchased by one of the heirs of Horace Henry, who endowed the museum that bears the Henry name, as a gift to the university, after it appeared in an exhibition at the Foster/White Gallery.

When the Henry Art Gallery was remodeled in the early 1990s, Dancer with Flat Hat was moved west of its original site, minus the donor's plaque, which disappeared during the move. Once easily visible from 15th Avenue NE, it can now be glimpsed in passing by those who know where to look -- on the landing of steps that lead from Schmitz Hall to the Henry Gallery. The original model for Dancer with Flat Hat is part of the University of Washington Hospital art collection. It was a gift from the Seattle Art Museum, 20 years after museum founder Dr. Richard Fuller (1897-1976), purchased it for $1,000 for the permanent collection.

Almost equally famous is Levine's Woman Dancing (1976), which stands on the east campus of the Washington State Capitol grounds, in Olympia. The 8-foot figure is caught with flying hair, poised to whirl on the ball of her left foot, a figure frozen in ecstatic motion.

Sculpture's Toll

Sculpture is heavy, sometimes brutal work. Over the years, Levine has had two artificial knee replacements, back surgery, and uncounted injuries to his hands, all the result of a lifetime of lifting and work with concrete and metal. It is a particular triumph, then, to give his work an air of lightness.

Triad, purchased in 1983 by Martin Selig, carries a look of gravity-defying weightlessness and freedom. Standing 14 feet high, it depicts a life-size male who supports a gesturing woman on each shoulder. The women fling out their arms in triumph, giving the piece the overall shape of an inverted triangle. The soaring feeling is emphasized by the figures' elongated legs -- not unlike those familiar from fashion illustrations. Similarly exaggerated legs are visible in the three multiracial striding figures of Interface, a 1982 Levine sculpture that is a focal point of Gene Coulon Memorial Park, in Renton.

In 1979, he completed a commission for the Southwest District Court, in Burien. Justice, a life-size woman, stands planted firmly on both feet, her arms upheld in a gesture of discovery. This is no stern woman in blindfold; her face is kind and open.

Walking on Logs

Levine memorialized a friend, the late musician and composer Hubbard Miller, with the title of his sculpture Walking on Logs, on a hillside facing the West Seattle Freeway. One of Miller's compositions bears the same title. Levine's sculpture, which shows four children playing, has been "adopted" by neighbors, who dress and accessorize the figures to celebrate holidays or fictional characters. On one occasion, dressed as characters from The Wizard of Oz, they held a huge sign that read, "There's no place like home, West Seattle."

Levine, a purist, finds such gestures exasperating. When he depicts figures clothed, garments are indicated as sheaths, without ornament, creating minimal impediment to the body. Neither gender nor beautiful features are important in these figures. Gesture and balance are central.

Because of the length of time needed to complete a major figurative piece, it is rare for Levine to have enough sculptures completed and unsold to mount an exhibition of large-scale work. He did so only once, for six months of 1996, at the Kirkland Public Library Sculpture Garden, where he placed seven large works and half a dozen smaller ones. For the most part, his solo exhibitions have focused on smaller works and maquettes.

Governor's Art Award

On May 23, 1997, Levine was awarded the Washington State Governor's Art Award in ceremonies at the Folklife Festival, at Seattle Center. The award was given in recognition of his many public commissions, as well as his activism in the causes of art and artists. For six years, ending in 1991, he served on the King County Arts Commission. He is a past president of the Alliance of Northwest Sculptors, and served as vice president of the Washington Chapter of Artists Equity. In the 1960s, he helped to found the Burien Arts Gallery.

Sensible of the honor the Governor's Art Award conveys, Levine nonetheless came to think of it as the kiss of death, since immediately after it was awarded, his work was rejected from 18 consecutive competitions -- unprecedented in his career prior to that time.

In 1997, he told an interviewer: "The artist is a conduit for what goes on in society and what goes on in art. You are hopeful that what you put into it leaves some room for other people to put their views into it, their feelings ... Part of doing art is to answer the question we all wonder: Why are we here?" (Cronin).

Levine died on September 19, 2021, in Seattle. Reported The Seattle Times: "Alert and active to the end, but on dialysis and suffering from ill health, Levine chose to end his life under the Death with Dignity Act" ("Phillip Levine, Whose Sculptures ..."). He was 90.