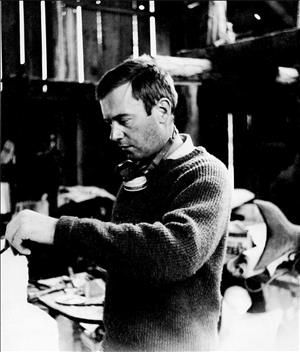

Artist Philip McCracken, known mostly for his bird and animal sculptures, was reared in Anacortes and began studying pre-law at the University of Washington. After his stint as an army reservist during the Korean War, he came back to the UW as an art major. Famed British sculptor Henry Moore accepted him as a student, and influenced him in lifestyle as well as in technique. Winner of the first Governor's Art Award in 1964, McCracken has been producing work from his Guemes Island home since the mid-1950s, constantly working under new themes, reinventing his work, and defying categorization. This biography of Philip McCracken is reprinted from Deloris Tarzan Ament's Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

Form and Idea

The key to Philip McCracken's sculpture lies in its conveyance of the delicacy and strength that coexist in nature. He has delved into areas so complex that the dimensions of meaning in his work have barely begun to be probed. As Christian Science Monitor art critic Theodore Wolff noted, "The first thing that strikes one about McCracken's work is that every piece of sculpture represents an extraordinary fusion of form and idea" (Wolff).

Skagit Valley Roots

In 1994, McCracken spoke of his art as a Zen riddle, saying, "The cosmos has become my Koan" (The Seattle Times, September 15, 1994). He was then attempting to portray the cosmos in sculpture. But for most of his life, the natural world of Puget Sound has provided his subjects. His family's Skagit Valley roots spread back more than a hundred years, from the time when his great-grandfather came west from Colorado to prospect for gold. The family struck it rich in another way: the Eureka Saloon, which his grandfather ran at the intersection of Fourth and Commercial Streets in Anacortes, 80 miles north of Seattle.

Philip's father was a merchant, at various times selling feed and grain, ice, and later, soft drinks. Philip was born November 14, 1928, in the hospital in nearby Bellingham. He was the youngest of three children. The eldest, Patricia, was 13 years his senior; William was 11 years older. Philip and his brother grew up spending much of their time outdoors, fishing and learning to hunt, taking summer vacations at the family cottage on Guemes Island, a mile across the water from Anacortes.

McCracken's earliest interest in art is traced to the time when, at age 4, he tried to carve a large boulder in the neighborhood. Only during his last year in high school did he begin to find painting more interesting than football. He graduated from Anacortes High School in 1947, and entered the University of Washington as a pre-law student.

When the Korean conflict broke out in 1950, he volunteered as an army reservist. His unit was promptly called up. He was sent to Fort Ord for basic training, then to Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, where, for a year, he worked as a gunsmith. He wears the tattoo of a large serpent up his left forearm as a memento of those days. In later years, he reports with some amusement, the tattoo made him the recipient of some "strange notes" in Japan, where such tattoos signal membership in the Yakuza, an organization with similarities to the Mafia (Interview).

Mentors

When he returned to University of Washington, it was as an art student. The School of Art had excellent facilities for sculpture, and professor Everett DuPen was generous about allowing students to explore new directions.

McCracken regards French potter Paul Bonifas, who was then teaching at the university, as his most important college mentor, for his bold ways with form. (Bonifas later moved to Guemes Island. Plagued by allergies to tree pollens, he soon left, but he is buried there in keeping with his wishes.) McCracken also was strongly influenced by carved-wood figurative sculptures in the Seattle Art Museum's (SAM) Asian collection, and by Taoist texts he had begun to read.

College was more than a four-year commitment. It was McCracken's practice to leave the university early each year to spend spring quarter doing commercial fishing. Income from fishing and from the G.I. Bill paid for his college education.

He graduated from the School of Art in 1954, having won the School of Art Prize, determined to be a sculptor. His work, which bore titles such as Rain Forest Forms and Heron already showed a marked personal style.

A Student of Henry Moore

McCracken asked himself who might be able to teach him how to navigate the real world successfully, how to balance life and work as an artist, about commissions and contracts. Who was the greatest sculptor in the world? "The answer was easy: Henry Moore" (Interview).

Shortly before he graduated, McCracken wrote to the British sculptor asking to be allowed to become Moore's assistant for a few months. Moore responded, "Send photographs." He did, and was swiftly invited to come to England. McCracken spent the summer and autumn of 1953 in Moore's studio near the village of Much Haddam in Hertfordshire, 25 miles north of London.

Moore had four other apprentices that summer: two Australians, and two English men. All received a modest stipend for their work. McCracken stayed at the pub in the village, a short bike ride from the studio.

An Artist and a Normal Human Being

Moore's lifestyle had a more profound effect on McCracken than did his art. From his acquaintance with Mark Tobey (1890-1976) and Morris Graves (1910-2001), both of whom "had lots of temperament," McCracken had perceived that being an artist meant living as a single-minded loner. Moore knocked that notion on its ear. A small, stocky man of cherubic vitality, Moore had a rich intellectual life, and was devoted to his wife and family. He modeled a socially integrated alternative to the lifestyles of the artists McCracken had known in the Northwest.

"Moore would come into the studio in the morning whistling. His young daughter would sometimes toddle in to watch us at work. Occasionally, we'd go to the pub for a beer, or watch wrestling on TV" (Interview). They broke for tea time, and great people such as Sir Kenneth Clark were apt to come to tea. When they talked business, McCracken paid close attention not only to terms, but to how such matters were conducted.

"Moore had time in the flow of time for everything. He channeled his energy into his work. He didn't have to cope with everyday dramas. I wanted the drama to be in my sculpture, not in my daily life. Moore always said, 'The main thing is just to endure; to produce daily, steady, focused work,'" McCracken recalled. "I learned, as Thoreau said, to build castles in the air, then put foundations under them" (Interview).

On the ship to England, McCracken had met and fallen in love with Anne McFetridge, a graduate of Mount Holyoke and Cornell Universities who was on her way to London to further studies of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British music, art, architecture, and literature. Her eventual aim was to write curricula for New York State high schools. At summer's end, she came to Much Haddam, where she and McCracken were wed in the twelfth-century Norman village church, with Moore as best man.

McCracken had grown up Catholic; Anne, Presbyterian. Their wedding was Episcopalian. Moore lent McCracken a necktie for the occasion, and paid the minister, who told him drolly, "Well, Henry, it's been a long time since we've seen you in this building" (Interview).

New York Respite

When Philip and Anne moved back to the United States, it was to a rural site near New York, for easy forays to the city's museums and art galleries. Graves, whom McCracken describes as "a generous spirit," introduced him to the Willard Gallery, one of the most respected in the city. It was an important introduction, since New York galleries, then as now, were swamped with artist applicants. When McCracken had earlier taken work in to the Knoedler Gallery, he was told, "Young man, you're the twenty-fifth person who's been in here this morning with their work" (Interview).

Marian Willard, who represented both Graves and Tobey, took on McCracken as one of her gallery artists. She had a key piece of advice for him: "Don't move to New York." She recognized that the Northwest zeitgeist was critical to the spirit of his work.

It was visible in pieces such as Black Mask, carved late in 1953. The black-stained cedar piece just over 2 feet high is redolent with associations of ritual masks and forest secrets. Dark eyes peer like an inner force from smooth, elongated concavities that give no hint of species.

Home to the San Juans

McCracken's work was going well, but he missed the skies and forests of the Pacific Northwest. In 1955, he and Anne moved to the McCracken family's waterfront cabin on Guemes Island. Today, the four-by-eight-mile island has slightly more than 300 registered voters. In 1955, it had 100 residents. A few of the islanders raise cattle, or have fruit trees. Others are artists, writers, designer craftsmen, and retirees.

Anne and Philip reared three sons in this unspoiled Eden. Tim was born on Labor Day, 1955. Seventeen months later, Robert was born, on Valentine's Day, 1957. Seventeen months after that, Daniel was born, on the Fourth of July, 1959. As the boys grew up, Anne took the eight-minute ferry ride to Anacortes to teach English in the high school, while Philip worked in his studio.

Fishing helped stock the family larder. In the spirit of Northwest Indians, McCracken religiously released the first salmon caught each year. The family's large vegetable garden was tended with the help of an old tractor dubbed Gertrude Stein, because on cold mornings it warmed up groaning, "A rose is a rose is a rose is a rose" (Interview).

A Studio Close to Nature and Weather

His first Guemes Island studio was a barn in a clearing rimmed with fir and cedar trees, with a shed nearby for goats and chickens. Living so close to nature, he was on intimate terms with predators. The hawks that struck his chickens provided the subject for his 1960 cedar sculpture War Bird, inset with arcs of circular saw blades. The violence of war is also visible in a related piece, Armored Bird, in the collection of the University of Oregon Museum, in Eugene.

His measured and exacting approach to materials, and his passion for creating form with the utmost clarity, translated into a well-organized studio. But nothing could be done about the fact that the studio was unheated and indeed unheatable. When he arrived in the morning to find snow covering his tools, and his casting water frozen, he moved his work to an old house fronting the beach.

Most artists undergo occasional dry periods. McCracken has never experienced a block, nor indeed any significant period of interruption in his work. Year after year, he has produced pieces of startling originality. Often he marries materials such as metal, stone, and plastic into carved wood.

Occasionally, his work has been fey and witty, such as the 1957 pewter Piping Rabbit, and the 1999 Future Artifact, a cigarette butt perfectly preserved in a bubble of amber attached to a matrix of petrified wood. Equally often, his work bristled with implied violence, such as Visored Warrior (1956), in the collection of New York's Whitney Museum of Art.

Spirit Birds

Birds have been his most enduring subject and symbol, particularly early in his career. They became sculptural models for his own inner states, especially for that part of his spirit that dwelled in the woods, at some times feeling caged and at others time snug, as expressed in Owl Home and Owl Family, both done in 1958.

"Things come out of the environment and get stored in my mind," he said. "Images and ideas make connections back of the curtain of consciousness, and re-emerge transformed. I don't examine them too soon. I don't want to violate that -- whatever it is" (Tarzan, "Honors for N.W. Artist").

Animal symbolism was a natural choice for his art, since the McCracken home was always alive with dogs, cats, rabbits, and wilder species. At various times, a tame crow, a fawn, a skunk, and a bad-tempered possum took their meals and their leisure with the family. When McCracken whistled a great horned owl out of the woods, it arrived from the forest depths with a rustle of great wings. Banking through the front door, it glided to a stop on its favorite chair in the living room.

Drenched with animal empathy as McCracken's early sculpture was, the forms also carried human meanings. That is doubtless why no one ever confused his work with wildlife art. The symbolic content is too manifest. His birds carry fire in the eye and vigor in their form, along with a spirit dimension.

Associative Emotion

From the beginning, his pieces carried a freight of associative emotion. Caged Bird, done in 1958 for the Seattle Center Playhouse, evokes frustration, claustrophobia, and restlessness for freedom. Blind Owl, in the collection of the Whatcom Museum of History and Art, in Bellingham, is as poignant for the clutching claws that anchor the blocky form to its solid perch as for the vast white stone eyes raised in an alert, profound attitude of listening.

Snowy Owl, which he smoothed out of Westchester marble in 1955, gave three-dimensional form to the kind of hollow-eyed birds that Graves was painting as stand-ins for human emotional states. The piece is in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum, having won the Norman Davis Purchase Award for a sculptor under 40 in the 1957 Northwest Annual Exhibition.

His work found appreciative collectors. When the Washington State Governor's Art Award was created in 1964 to honor the state's outstanding artists, McCracken was its first winner.

Self and World

For McCracken, art is a spiritual journey -- an exploration of what it means to be alive. Experimentation is at its heart. He describes art as "an evolving process of having new understandings of Self and the World revealed to you. In a sense I feel as I once did as a child, investigating the attic when no one was at home -- looking through all the mysterious but somehow familiar things, yet realizing -- with a certain elation -- the dangerous possibility of finding out what I shouldn't know" (Graham, p. 48).

When a student asked him, "How do you become an artist?" he replied, "First risk your life."

"Why make art?" he asks rhetorically. "Part of it is a payback for some of the great art and music and sculpture that has made life so richly livable. We can talk all around the subject of art, but the essential part of it can't be nailed down."

In 1974, McCracken completed a carved cedar piece titled Medicine Wheel, in which four concentric indented circles are overlaid by runic solids whose forms express a cosmic sea. The motifs find echoes in Guy Anderson's paintings, and in the late paintings of Richard Gilkey.

Concrete Poetry

But it is Graves who seems his nearest spiritual kin, especially in pieces such as Bird Song, in which song issues as a slender, curving shell from the upthrust beak of a bird carved from alder. Completed in 1964, it marked a transition into sculptural assemblage, using seashells, smooth stone, leather, and metal elements. In 1966, he rendered Poems as limpets, bear claws, a walnut shell, sea urchin spines, and porcupine quills set in spare lines on an open wooden book. It may be the only time in the twentieth century, and possibly the only time in history, that a sculptor has given form to poetry as text.

In his 1970 exhibition at the Willard Gallery, McCracken introduced new media: flowers, hornet's-nest paper, bark, bird nests, and the wild rose bush. Gold wire and gold leaf created cellular nuggets of Wild Honey in dark cedar.

Political Unrest and World Distress

Not all of his pieces were derived from the natural world. The chaos of the Vietnam era and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy spread to pastoral Guemes Island as it did to all of the United States. It became visible in McCracken's work. In I Saw, a circular saw blade rips through a smooth white field of canvas, leaving a tatter-edged gash that can never be restored to its pristine state. It is a visible representation of violated innocence.

Bullets and broken glass seemed apt visual metaphors for the political climate. In the 1967 Lights Out, bullet holes riddle an acrylic sheet, having shattered four out of a line of five electric bulbs. The solitary remaining lightbulb stands like a fragile survivor of terror and war. The viewer unconsciously awaits a final shot from the hand of an unseen sniper. The piece is in the collection of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Canada.

Lights Out is remarkable on several counts. First, for the visual tension it creates in the viewer; second, because it establishes emotions of threat and fear in a simple, vivid way. Third, it translates an electric moment -- someone shooting with intent to kill -- into an enduring visual form. (Translations of fleeting, overpowering moments into sculpture are rare. Another exists in SAM's Asian Collection (36.Ch11.28), in the form of a life-size carving of a monk at the moment of enlightenment, by an anonymous Y�an dynasty (fourteenth century) Chinese artist.)

Inspired by Skylarks

A major recognition of his status as an artist was a commission from the King County Arts Commission to create a work for the Kingdome in 1978. In the summer of 1977, when Philip and Anne were in England to visit the Moores and to research upcoming sculpture commissions for the Kingdome and another for a Benedictine monastery, McCracken went to the British Museum to revisit the Elgin Marbles, and to see Greek relief sculptures of birds and animals done around 470 B.C.

The next day in Sussex, he woke at 5 a.m. to the song of skylarks. In the course of 10 minutes, he drew a series of five simple bird shapes, which he translated into 25 x 26-inch bronze bas-reliefs for the Kingdome. (The panels were moved to the King County district courthouse, in Issaquah, prior to the implosion of the Kingdome on March 26, 2000.)

Lemons Listening

After they were finished, he found relief from the intense focus of their production in a series of small, humorous tableaux formed of elements including worn-out scrub brushes and plastic fruit. Three dried lemons form an attentive semicircle before an elevated plastic lemon in a piece titled Lecture. In Visit, two plastic bananas hover upright over a blackened dried banana recumbent on a wooden bed. In another piece, a tattered work glove gallantly receives the gilded hand of a mannequin.

The new work was a jolt to New York Times art critics, who had once seen his work as "Brancusi variations on a Thoreau theme" ("Art's Well on Capitol Hill"). It also bewildered collectors who had been enthusiastic about his nature themes. But even before reaction could be voiced, McCracken had picked up his paintbrushes, which had lain idle since his student days, to produce a series of landscapes and seascapes, defying critics and collectors to categorize him.

In 1980, the Tacoma Art Museum mounted a major retrospective exhibition of McCracken's work. Colin Graham, director emeritus of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, wrote the introduction to the show's catalog, published by the University of Washington Press. The picture on its cover is Moon, one of the most evocative pieces of his career. The dented shape of a pearly full moon carved from cedar emerges from a "sky" whose rippling fullness creates strips of shadowy cloud. It is a work of pure poetry. Graham wrote:

"To those living sealed off from the natural environment in the great North American conurbations, his bird and animals often have little to say apart from their formal qualities. But to those whose sympathies embrace the totality of organic life his work has a compelling attraction; and among that growing body of people who live with an acute sense of values lost under the onrush of technology his spirit-saturated pieces tend to evoke feelings of enchantment tinged with nostalgia" (Graham p. 40).

Potatoes On Show

The only nostalgia that could be surmised in connection with McCracken's next series was for Irish ancestors who came to the United States during the potato famine. The drawings showed rays streaming from the interior of potato forms, bursting them with life energy. They suggested the potato as a carrier of beneficent, healing earth energies.

The drawings evolved into sculpture of surprising beauty. A calm intelligence seemed to gaze out from half a dozen onyx "eyes" set in the meltingly smooth cypress form of Potato with Eyes II. "They weren't planned or calculated," McCracken said, "they just arose. I tend to trust that kind of intuitive energy. I'm having another look at humble things -- the kind of life that we ignore and take for granted, because I think there's a lot of significance in such things" (The Seattle Times, February 2, 1986).

The series, first shown in New York's Kennedy Galleries, prompted Christian Science Monitor writer Theodore Wolff to write, "The genius of art after all lies in the ability to transform the ordinary into the extraordinary; to take the most everyday of subjects and to turn it into a thing of beauty, wonder or delight" (Wolff).

In Seattle, the From the Potato Patch show appeared in McCracken's only exhibition with the short-lived Lynn McAllister Gallery, at 601 2nd Avenue. It was the gallery's inaugural exhibit. Poet Jim Bertolino read "Potato Poems" at the opening on February 2, 1986.

McCracken wrote:

"Much of my work in the past has been in the form of creatures of the air. The works here are the antithesis of the air-borne, yet they spring from the same source. Crooked carrots, winking potato eyes, parsnip twins; good-natured and humorous, tuber and root forms are often antic as well as good to eat. However, they carry many other meanings. They are also conscious, message-bearing, high energy states of dancing molecules, and in their earth-cast forms are deeply expressive of the wisdom of the earth" (Artist Statement).

Scientists had shortly before found that a potato in the ground "knows" when the moon is over the horizon. McCracken noted, "The little lump is in touch with the cosmos" (Artist Statement).

Translating the Cosmos

The cosmos was to become his next theme. By 1989, he had gone from the earthy to the ionosphere, translating shooting stars and galactic events into sculpture. From the time he was a child sleeping out of doors under the stars, he had connected the stars in his mind with invisible lines that marked the boundaries of three-dimensional forms, rather like the ancients who imagined star clusters as figures of the horoscope. But unlike ancients who saw human and animal shapes in the stars, McCracken realized that his imagined shapes would be measured in light years -- irregular, faceted shapes with precise, unexpected angles and razor edges that mark the apexes of stars. Once again he did the unexpected, creating the shapes from flawed wood.

"Forty years ago when I first began sculpting, I thought I had to have clean, clear, old-growth cedar," he said at the time. "Now, I like working with ornery wood, full of cracks and dynamics" (The Seattle Times, September 15, 1994). He made a strength of such "weaknesses," laminating small, irregular chunks together, sandblasting the surfaces to define and carve out weak areas. Voids were embedded with infills of bright-colored resin. Polished to a lapidary sheen, the insets suggest suns exploding in dark distance, or the trace of a meteor flash. The curling grains of pear and apple wood were transformed into the suggestion of a swirling cosmos inset with points of light. It was a visual reminder that in trees as in the cosmos, similar forces swirl.

Archeology of the Future

By 1999, his work had metamorphosed further, to what he called an Archeology of the Future. In his studio, laid out with dozens of work benches, each with its own work lamp, its own tools, and its own piece in progress sitting shrouded until he is ready to work on it ("I don't what them all talking to me at once"), are "artifacts" such as a flip-top ring from a soft drink embedded in red rock, and the long-jawed fossil skull of a deer-size creature conceived in McCracken's imagination.

He has said:

"The imagination is a siren. It draws one onward. The exploration, the adventure, is worth the hazard of going on the rocks. Sometimes it is dangerous — the imagination fires in so many directions it sends one's brain crashing against its walls — a loose cannon on deck in a high wind. At other times it leads with a kindly hand where one can look quietly this way and that at all the amazing things passing — vibrant, resonant with life" (Philip McCracken).Decades of working in the midst of wood and stone dust, and chemicals, have taken a toll on his lungs, but his impish, visionary approach to sculpture remains intact.

He works intuitively. He once said, "If I knew what these pieces meant, I would probably never do them. They are not exercises in what I already know, but explorations into what is mysterious and unknown to me" (Graham, p. 9). This is the heart of his mysticism. Regardless of whether the outer appearance of his subjects is animate or inanimate, their content is human and universal.