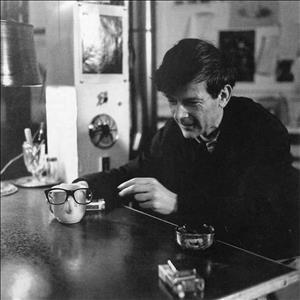

Wesley Wehr, a gifted musician at age 19, was invited in 1949 to tutor the painter Mark Tobey (1890-1976) on the piano. Thus began Wehr's close relationship with Tobey and ultimately with all the artists and friends of the Northwest School. Wehr kept letters, recorded statements, and took notes of conversations. His archivist leanings have greatly helped preserve knowledge of these artists' lives and work. Tobey encouraged Wehr to pursue painting and he created masterly miniature landscapes that have garnered him wide recognition. In later life, he explored his passion for archeology and paleobotany and became a curator at the Burke Museum. He is author of a memoir of the artists of the Northwest School, The Eighth Lively Art: Conversations with Painters, Poets, Musicians, and the Wicked Witch of the West. Wesley Wehr died of a heart attack on April 12, 2004. This biography is reprinted from Deloris Tarzan Ament's Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

The Collector

Records of past life, from preserved snippets of conversation to fossilized impressions of leaves in shale, have been Wesley Wehr's abiding passion. Wehr entered the art world through friendship with Mark Tobey. In ensuing years, he has contributed enormously to our understanding of Tobey and of the painter Helmi Juvonen by virtue of meticulous notes he kept on his conversations and correspondence with them. They are but two of the painters, poets, and musicians whose words he recorded. For the most part, his subjects had no inkling their thoughts were being archived (Wehr Papers).

Wehr is one of those rare men who make a modest living doing precisely those things that most entertain and engross them. He is a musician, a paleontologist, and an artist who turns out tiny landscapes that look like they could have been lifted from specimens of agate. Alternately, he creates cartoon-style miniature drawings of otherworldly life forms. Half amusing, half disturbing, the very size of these Wehrian alter egos seems to say, "Oh, don't pay any attention to me, here, you have to move in closer if you want to really see me, and as i was saying, i'm certainly nothing for you to bother about, did you miss this little line behind my middle? It just could be a tail, you know. Anyway, i'm just a little doodle, you just drift on over and look at that big old encaustic in the corner, he's the real artist, i'll just see you again later, after you're asleep i'll peek in and see if you're okay, don't you worry about it even if some of these other animals traipse along after me and if there's anything you'd like to tell me you just go right ahead."

"The drawings come out of my Nordic, somewhat cracked-across-the-brow side," Wehr said:

"Oddly enough I do somehow believe that such critters exist somewhere. My father, of all people, one day said, 'Oh these aren't monster drawings, these are forms,' and that stopped me cold, because he was absolutely right. I was glad he had that reaction to them. They resemble little figures and things, but the concerns going on in them are rather formal, balances and curved lines, rectangles, cones, they'll end up looking like some figurative thing, but the actual concern while I was working on them is checks and balances, combining abstract forms and diverse forms from nature, insect wings, bits of plant. While I'm doing them I take from anything. Some things from the insect world, or plant foliage, it doesn't matter. Biologically they're reconstituted elements from nature" (Wehr Interview).

Norwegian Roots

Wehr was born April 17, 1929, in Everett, the only child of Conrad and Ingeborg (Hall) Wehr. His father ran a Texaco service station. His mother taught elementary and junior high school before his birth. She was a native Northwesterner whose parents came from Norway to settle in Stanwood in the early years of the twentieth century. Later they moved to Camano Island.

Wesley showed an early talent for music, which his parents encouraged with private lessons. At Queen Anne High School, in Seattle, he was recognized as a gifted student, whose ambition was to be "a combination composer and archeologist." His discontent with high school centered around the fact that "I was the skinny kid. Girls wanted to mother me."

He was a senior when his compositions "Pastoral Sketches for Violin and Piano" and "Spanish Dance" resulted in his being invited to study privately with George F. McKay during summer session at the University of Washington. He entered the university in 1947 as a music major.

Wehr Meets Mark Tobey

In the summer of 1949, when his composition teacher Lockrem Johnson was out of town, piano teacher Berthe Poncy Jacobson suggested Wehr tutor one of her students who was also one of Johnson's private-study students, but less advanced than himself. That is how Wehr, at 19, found himself tutoring Mark Tobey, then 59. Tobey described himself to Wehr as having been "a fashionable portrait painter in New York," saying it was a scene he "got tired of."

Wehr recalls Tobey as "unteachable": "He didn't want a teacher, he wanted an audience. I would assign him a problem, and he would come back and play something he had composed that had nothing whatever to do with what I had assigned" (Ament Interview).

Despite the difference in their ages, Wehr and Tobey became friends and confidantes. When Wehr stood outside Tobey's Brooklyn Avenue studio and shouted to be let in (an act requiring a voice volume unimaginable to most who know Wehr), Tobey would peer out the window to verify who was there, and admit him. Wehr sat on the floor watching him paint while Tobey explained what he was doing and why. Wehr took notes.

Tobey gave a Christmas party that year, at which Wehr met Morris Graves and Guy Anderson. He described Anderson, a strikingly handsome man, as a cross between composer George Gershwin and dancer Gene Kelly. Wehr thought that Anderson came closest of all Northwest artists to being a "Zen master."

In his senior year, Wehr attended the poet Theodore Roethke's class, and began to immerse himself in writing poetry. He graduated with a master of arts degree in 1952, a winner of the Lorraine Decker Campbell Award for original composition. He took a weekend job at the Henry Art Gallery as a watchman. When visitors were few -- as they usually were -- he doodled sketches.

Not until 1957 did he publish a musical score, Wind and the Rain, with Dow Music in New York. By then, he had already ceased to compose. "The whole thing collapsed when Roethke said, 'Wehr's got it!' I became self-conscious; afraid of making mistakes. The life went out of it."

From Music to Painting

He turned his creative energy to painting during the Christmas holiday of 1960. His friends had left town, gone home for the holidays. "That year was a great turning point for me," he recalls. "My friends were winning awards, and Little Wessie couldn't finish anything. I had no future. I couldn't compete with anyone."

He was scraping by with a job at Hartman's Bookstore on University Avenue. "I felt I wasn't cut out to make a living at anything. It's a purification to realize that all is lost. I was walking down University Way, and I walked into a drug store. Ravel's Shéhérazade was playing, and it suddenly struck me that there is so much beauty in life." He saw a bright yellow box of Crayolas on the shelf, and jars of poster paint:

"I bought them. I sat on the floor of my room and pulled everything out of the bag. I cautioned myself to be realistic. We destroy ourselves when we aim too high. If I work in tempera, I thought, I'll compare myself to Tobey and Graves. I was surrounded by giants. I told myself to forget about painting.

You don't know how to draw, I told myself. What's your strong point? Color. So I decided I'd do a painting based on color. I drew a line across the paper. I looked at it and said, Ah, that's a horizon. What's my life really about? The Oregon coast, and petrified stone. And I thought, I want to realize my feelings before Nature. I painted to do something for myself."

He created a few small landscapes and seascapes less than 6 inches to a side, rendered in dense, deep colors that resembled the strata of picture agate that sometimes emerges from the interiors of thunder egg rock specimens. "Tobey was wonderful. He told me that he didn't find himself until he was fifty. He counseled me, 'Whatever you're doing, give it everything. Give yourself time. Don't be in a rush. Give in to everything you love. Let it take over.'"

His Paintings are a Hit

The miniature landscapes received favorable comments in the 1961 Puget Sound Area Exhibition at the Henry Art Gallery. In 1962, Wehr's work was accepted into the Northwest Annual Exhibition. Tom Robbins, reviewing the show, wrote, "This should be remembered as the art show in which Wesley Wehr finally convinced everyone with unimpaired vision that he is the most underrated painter in the Pacific Northwest" (Robbins).

The acclaim for the paintings is all the more remarkable for having occurred in an era when painters in New York were setting the pace with gigantic, wall-filling canvases that measured success by the square yard. Composer Ned Rorem wrote to Wehr, "You are a jeweler who does not work with jewels, a cameo artist who eschews the human profile, a goldsmith who works only in paint" (Rorem to Wehr).

The rich surfaces emerged from his method of placing paper on a hot plate after he had drawn on it with wax crayons. When the wax melted and was partially absorbed into the paper, Wehr burnished it to a heavy gloss. He employs a cadence of colors to establish gradations in the intensity of light and achieve effects of remote depth. Bands of muted color become a chromatic plain chant. A ripple of dark hills shimmers in dusky haze. Like a forest glimpsed at night, a Wehr painting is an evocation of loneliness. "I want to synthesize Mondrian and Albert Pinkham Ryder, and that Gothic sense of dark and distance in Graves. But I think the sense of my paintings comes from Tobey," he said (Ament Interview).

Recognitions

His art first appeared in solo exhibition at the Otto Seligman Gallery, in 1967. Two years later, in 1969, it was shown at the Francine Seders Gallery, and at the Humboldt Galleries in San Francisco. His work was selected for inclusion in the Washington State Pavilion at Expo '70 in Osaka, Japan. That same year, he received his first solo museum exhibition, at the Whatcom Museum of History and Art in Bellingham. His career was well launched.

In 1973, his paintings appeared in a solo exhibition at the Shepherd Gallery. By 1976, he had gone international, with a show at the Galerie Rosenau in Berne, Switzerland. In 1977, he again had a show at the Galerie Rosenau in Berne, adding to it exhibitions in Basel and at the Gallery of Modern Art, in Munich. Everywhere the paintings were shown, they enchanted viewers.

Poet Elizabeth Bishop, a longtime friend of Wehr's, wrote:

"I have seen Mr. Wehr open his battered briefcase (with the broken zipper) at a table in a crowded, steamy coffee-shop and deal out his latest paintings, carefully encased in plastic until they are framed, like a set of magic playing cards. The people at his table would fall silent and stare at these small, beautiful pictures, far off into space and coolness; the coldness of the Pacific Northwest coast in the winter, its different coldness in the summer. So much space, so much air, such distances and loneliness on those flat little cards ... who does not feel a sense of release, of calm and quiet, in looking at these little pieces of our vast and ancient world that one can actually hold in the palm of one's hand?" (Bishop).

Colin Graham, director of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria in British Columbia, called Wehr "the poet of the moody skies of the Pacific Northwest," saying: "He is an ardent observer of their heavy cloud masses and their finely nuanced changes of tone and light, especially at crepuscular moments. The fact that he is a trained musician and composer helps to explain why his landscapes and skyscapes are suffused with a quiet kind of visual music" (Graham). Graham curated a retrospective exhibition of Wehr's paintings at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria in 1980.

The Archeologist Emerges

"After the retrospective in Victoria [1980-81], I started to paint less and less," Wehr said. "For one thing, in 1977 I had gone to the little gold-mining town of Republic in the Okanogan Highlands with a young paleontologist, Kirk Johnson, where we stumbled upon an outcrop of 50-million-year-old fossil flowers, leaves, insects and fish specimens, all beautifully preserved."

A woman from Republic had sent the Burke Museum, on the University of Washington campus, a fossil flower found near her home. Wehr and Kirk Johnson (in 2002, associate curator of paleontology at the Denver Museum of Natural History) drove to Republic to see whether they might find something similar. By the end of their second day of prying back layers of shale, Wehr realized they were on the edge of a major fossil field. Over the years, the area he and Johnson discovered that day -- a buried lakebed some 50 million years old -- has produced more than two hundred species from prehistory. Smithsonian paleobotanist Scott Wing called it "an exceptional site," saying "There's certainly no place like it in North America, and probably not in the world" (Chasen). The outcrop still yields astonishing fossils, which have rewritten parts of the story of the evolution of flowering plants and the history of the origins of Northwest forests.

After Wehr began to collect there, he coauthored scientific papers with paleobotanists around the world. "I did little drawings now and then, but these fossil discoveries brought me into a world of paleobotanist friends who had a sense of community which I had experienced on University Way with Helmi, Pehr Hallsten, Tobey, and Guy, and younger artists such as Neil Meitzler and Paul Dahlquist during the 1950s," Wehr said.

At the Burke

In 1978, Wehr was appointed affiliate curator of paleobotany at the Burke Museum. He came to his latter-day vocation via a route that began with collecting agates on the beach at Camano Island as a child. As he grew, he made backpacking trips into the Ginkgo Petrified Forest in Eastern Washington to collect fossil specimens, and visited rock shops to buy mineral specimens.

Tobey had told him years before, "I think it's going to be that hobby of yours, rock-hounding, that will save you." In the late 1960s, in a rock shop in Medford, Oregon, he bought a piece of petrified wood labeled as white pine. Wehr thought the label was wrong. It looked to him like a fern stem. A fossil-fern expert at the University of Montana who examined the piece agreed, adding that the fern was a previously unknown species. He named it Osmunda Wehrii in Wehr's honor. "The idea of having something named after me seemed very exotic," Wehr told Daniel Chasen, a writer for the Seattle Weekly (Chasen).

He began to hang out at the Burke, examining its then-modest collection of minerals and petrified wood, cataloging the collection on a volunteer basis. When Burke officials offered him an affiliate curatorship, he protested that he had no formal training. They were not concerned. Although the Burke could not afford to pay him, Guy Anderson began sending checks to support his work in paleobotany, explaining, "Mark [Tobey] used to send me money when times were tight; now it's my turn" (Chasen).

The Stonerose Interpretive Center at Republic, the site Wehr and Johnson brought to the world's attention, receives on average 7,000 visitors annually. Stonerose curator Lisa Barksdale says people come from around the world to dig there for fossil flowers, leaves, insects, and fish. The site has yielded many of the Burke's most spectacular fossil specimens, a great percentage of them dug by Wehr and his artist friends. In 1981, Wehr discovered the fossilized remains of the oldest known fir tree, and the remains of the oldest known cherry leaf (Prunus andersonii), which he named after Guy Anderson. He wrote about the fir tree discovery in a paper coauthored by Howard E. Schorn at the University of California, Berkeley. He also discovered a 50-million-year-old flower, named Wehrwolfea, for himself and Jack Wolfe, who was with the U.S. Geological Survey at Western Washington University.

The Wes Wehr Endowment for Paleobotany ensures that his work will continue. Wehr's lair in the Burke's lower level contains flat files of prize fossil specimens, interspersed with drawers filled with Helmi's art, and his own work. Surveying the place, he likes to joke that after years of work, he scratched and clawed his way to the top of the basement.

Tobey remained a strong force in his life even after Tobey's move to Switzerland. In 1985, nine years after Tobey's death, Wehr went to Europe, in a swing that included London, Paris, Berne, Basel, Colmar, and Strasbourg. "Several wonderful weeks, seeing all that glorious art again -- and all that chocolate." A few years later, he traveled to Madrid for the opening of the Tobey show at the Reina Sofia Museum, and spent a day in Toledo, Spain.

The Mineral Connection

Credit Wehr with pointing out the close similarities in Mark Tobey's paintings to mineral specimens in Tobey's collection. (Rock specimens from Tobey's collection are now in the collection of the Burke Museum.) His fascination with crystals is readily visible in Tobey paintings that bear titles such as Agate World. A 1961 lithograph, Winter, suggests both falling snow and a specimen of snowflake obsidian.

Wehr recounts that he and Tobey often visited natural history museums to look at crystals, minerals, and fossils, whose forms, textures, and colors Tobey studied. On one occasion when they were looking at rutilated quartz crystals, Wehr says, "Tobey pointed out to me how the slender, dark crystals of rutile, penetrating in all directions the space of the clear quartz crystal prisms, seemed to penetrate perspective." Both saw it as nature imitating art.

"He understood the underlying unities of nature and society," Wehr says. In a 1988 Tobey retrospective he curated at the Cheney Cowles Museum in Spokane, Wehr showed Tobey's paintings side by side with mineral specimens they resembled.

"I am not an abstractionist," Tobey once told Wehr. "I am a humanist and a naturalist." By which he meant, Wehr explains, that he had gone past resemblance and entered into the biological rhythms of life itself. Tobey also told Wehr, "If I were to paint what I want to, I'd paint men. But I have this concern for space, and how do you reconcile the two in a picture?" (Wehr Interview, 2000)

As paleontology absorbed more of Wehr's time, he did not regret painting less:

”The art scene when I wandered off into paleontology was becoming increasingly competitive and career-oriented. Matthew Kangas [a freelance Seattle art critic] was a divisive and malevolent force in the scene, pitting artist against artist. I took sanctuary at the Burke Museum and stepped out of an art scene that had become alien to the spirit that permeated the life I'd known. Then one day Gordon Woodside said, 'You still have some good work in you. If you ever get back to painting, I'd like to exhibit your new work.' That got me down to work."

It resulted in a show in September 1987, in conjunction with paintings by Paul Havas. Wehr's paintings were featured again at Woodside/Braseth in July 1989, in conjunction with an exhibition of Mary Randlett photographs.

A Friend to All

Wehr celebrated his 70th birthday with a March 1999 exhibition at the Collusion Gallery in Pioneer Square, adopting a tradition familiar from Northwest Coast Native American potlatches in bestowing a gift on each guest -- an original Helmi doll drawing. He said:

"The Collusion Gallery group brought me back into what it's like to have dealers you can truly like as friends, and not just a temporary business arrangement. Having lived long enough to see this enshrinement of the Northwest School, I realize that when we glorify the past we don't do it a service. I have to beware of becoming a fossil. Still, when one starts out as the kid in the gang, one stays that way inside. I was the kid around Tobey and that group of painters."

A decade after Tobey's death, Wehr donated Tobey's dressing robe to a fund-raising auction to support a new building for the Museum of Northwest Art. "I don't want people to get the wrong idea," he said. "It's not the Shroud of Turin." It was vintage Wehr.

Wehr had been a friend of Helmi Juvonen since his student days at the University of Washington. After she became a ward of the state at Oakhurst Convalescent Center in Elma, Washington, in 1960, he maintained a close and caring relationship with her, shepherding her art into the collections of Northwest museums and curating exhibitions of her art. He curated Helmi exhibitions at the Frye Art Museum, in 1976; at the Nordic Heritage Museum, in Seattle, and at the Washington State Capitol Museum and Evergreen State College, in Olympia, in 1984; at the Whatcom Museum of History and Art, in Bellingham, in 1985; and at the Cheney Cowles Museum, in Spokane in 1986.

After her death in 1985, Wehr did archival research to publish the lengthy correspondence between Helmi and Morris Graves during the years Helmi was at Oakhurst. For more than a decade, his work at preserving the work and the words of Helmi and of Tobey supplanted the creation of his own art. He considers it time well invested. "Our reputations," he says, "are based on how our work reproduces." Asked to comment on the collective body of his work, he shrugs. "I just wanted to look at the sky and collect agates" (Hanley).

Wesley Wehr died of a heart attack on April 12, 2004.