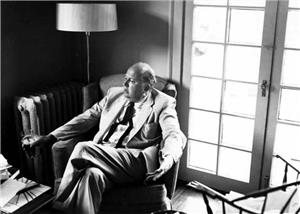

This remembrance of the poet Theodore Roethke (1908-1963) was written by one of his former students, James Knisely. Knisely is author of a novel, Chance, An Existential Horse Opera (Mwynhad Press, 2002). He writes: When I was a student at the University of Washington in the early sixties I was blessed with one of those experiences we are rarely lucky enough to stumble into: the chance to study with the poet Theodore Roethke. When I recently read Patrick McRoberts' History Link article about Roethke I was impressed with the way in which McRoberts captured the spirit of this unusual man, and I realized it might be useful for those who knew him to get our recollections on record before we too pass, and our memories of Roethke with us.

A Mad Genius Recalled

I didn't know Roethke well, so I'm not the best qualified to speak of him now. I studied with him for six months in 1962. As I recall, students were allowed to study writing with him (for credit) up to two years, and to take his poetry reading course for a couple terms more, so some of his students were disciples, really, and knew him much better than I did.

As a result, many of my memories of Roethke are nothing more than impressions and recalled rumors; but some of those may be of interest.

I had three strong impressions of Roethke. One was that he was (as everyone said) a mad genius. As a naive kid I was willing and eager to believe that, but much of what I saw in him seemed to confirm it. I was almost surprised when he seemed to display a sober and rational side, but he was, after all, a functioning member of society and the University community who was able to write and teach and do the other things a man has to do to get by in life. Even so, I had the sense that he lived not far from the edge. And I was in awe of his genius, which he radiated in a kind of humid, short-breathed way.

Another was that he was a passionate man. He seemed to live very much in his feelings, and his feelings were sometimes rather strong and possibly not always very cautious.

It was also clear that he a passion not just for writing but for teaching. He seemed to pour himself into sharing his craft with his students, so that there was often an energy in his class that could almost be seen (and could certainly be heard) as well as felt. Studying with Roethke was a heady and exhilarating experience which I understood even then to be of a kind I would probably never have again.

As to his illness, there was a story that the men in white had come for him one day while he was teaching a class at the U. McRoberts cites a hospitalization in 1935, but my impression was that he'd had more than one, and when The Far Field came out in 1964 I understood some of the poems (eg "In a Dark Time") to refer to episodes more recent than 25 years.

I do recall an incident that gave me a glimpse, perhaps, of Roethke's daemon. He had been given an award or honor of some sort. I can't remember whether it was an award he had just received or whether on this occasion he was recalling the Pulitzer ceremony or something of the sort. But as he was describing this award ceremony to his class one day, he told us he had found himself seated on the dais next to Edward Teller, "the father of the H-bomb." Roethke told us he had always held Teller to be an evil man, and finding himself seated next to the guy was so unsettling even in memory that as Roethke recounted the event he grew so agitated that he was shouting and flailing his arms, red in the face and (as I recall) sweating profusely, telling us how much he hated the evil that son-of-a-bitch had unleashed into the world.

In the midst of this rant Roethke stopped himself and looked around at us, his students, then somewhat sheepishly shrugged, and laughed in an impish way he had, then simply resumed his teaching.

Like most people, I guess, I have come to assume that Roethke's illness was bipolar disorder, so I was interested to read in McRoberts' piece that his illness was never diagnosed. It may be that they didn't know much about manic-depression at the time. I can say that in addition to Roethke's occasional flights into exhiliration and agitation, he seemed at times morose and withdrawn, so that's consistent. But most of the time he was a charming and engaging if somewhat imposing man.

I remember another time he had a recording session one morning for a record album he was cutting (I think it was selections from Words for the Wind). When he came to class that afternoon he was a good two or three sheets to that very wind. He explained in the exaggerately sheepish manner he sometimes donned that he had taken "a little bubbly" to relax himself for the reading. But mostly I think he was always sober in class.

When Roethke autographed my copy of Words for the Wind, he signed it "with a real affection." He did have great affection for his students, I think. Part of his legend, in fact, was his fondness for young women, and although I believe his affections were often innocent, they may often have been sexual as well.

It is in that context that I have always read "Elegy for Jane." When he agonized over the the right he did not have, "Neither father nor lover," to mourn for Jane, I always felt the poem gained a dimension from the notion that his attachment to Jane (a student) was that of both a caring mentor and a would-be lover who had lost his chance.

One sunny afternoon I had to drop by his house to turn in a paper I had failed to submit on time. He met me at the door and after accepting my paper, he invited me to come in and play bocci with him. When I explained that a buddy of mine was sitting in the car and I'd have to invite him to join us, Roethke abruptly changed his mind and said he really had to grade papers and shouldn't take the time to play -- and so my chance to play bocci with the master was gone with the breeze.

Although he was known to hang out at the Blue Moon Tavern in the University District, he also drank at the original Red Robin, which was also something of a bohemian joint at the time, and much closer to his home. So one day in the spring of 1962 our class retired to the Red Robin to celebrate with him his 54th birthday. I don't remember much about the party except that under Seattle's peculiar blue laws of the time we couldn't carry our beers to our table from the bar. Roethke seemed to enjoy with plenty gusto spending the afternoon of his birthday drinking with his students.

I also remember a story that when Dylan Thomas came to visit Roethke in Seattle (I think they drank together at the Blue Moon) Roethke tried to get him a position at the UW, but the chairman of the department couldn't deal with the thought of two of these wildmen at once, so he rejected the idea out of hand. I don't know whether there's any truth to that story.

I read with interest McRoberts' report that Roethke was thin and sickly as a boy. In his fifties he was a large, fleshy, imposing man who walked with a stifflegged shuffle. The story was that he had injured his knees or had developed arthritis, something of the sort, but I remember his boasting in class one day that he "could have taken Hemingway in three rounds."

I also recall a story according to which a hospitalization for knee surgery had led Roethke to an addiction to morphine. The rumor or at least the implication I recall was that he might still be addicted. That one had the feel of rumor pure and plain. I think his students were always eager to add to his mystique.

For all his towering passions and genius and fame, Roethke was personable and accessible and cared about his work, a mad genius with a passion for teaching. An amazing man. A fascinating portrait of him by Mike Nease hangs today in the Blue Moon. Everyone who cares about Roethke or about genius or about poetry, even a little, should visit that painting at least once.