O. O. Denny Park, named for Orion Denny (1853-1916), son of Seattle founder Arthur Denny, is located on Finn Hill, northwest of Juanita, on the Eastside of Lake Washington. The property was Orion's country estate, and his widow willed it to the City of Seattle. Seattle continues to own the park and for years operated it as an overnight campsite for Seattle children. Later King County managed it for the City as part of the King County park system. Today (2005), on behalf of the City of Seattle, the Finn Hill Park and Recreation District manages the O. O. Denny Park for the enjoyment of all.

First in the City

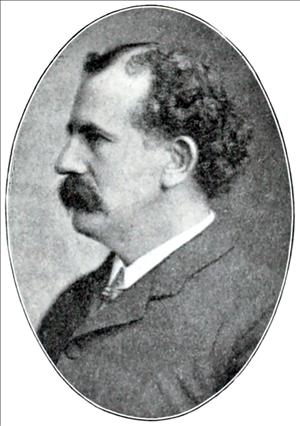

Orion Denny, son of pioneers Arthur and Mary Ann Denny, was the first white boy born in Seattle. He was born on July 17, 1853, in a log cabin on the corner of what is now 1st Avenue and Marion Street in Seattle. At the time, the cabin also served as Seattle's first post office.

Denny was one of the first students at the Territorial University, where he trained in marine engineering. Upon graduation, he served as chief engineer aboard one of his father's boats, the Libby. Later he served for 20 years as chief engineer aboard the Eliza Anderson, one of the more memorable boats of Puget Sound's Mosquito Fleet.

In 1874, Orion married Eva Flowers Coulter, but they divorced a few years later. Following his marriage to Narcissa Latimer in 1889, he decided to take a more "down-to-earth" job, and was named vice president of the Denny Clay Company in Renton, a business owned by his father.

Klahanie

Although he was now a successful businessman, Orion never lost his love of travel and open water. He and his wife bought a 46-acre tract along Lake Washington north of Kirkland, to which they enjoyed escorting guests aboard the S. S. Orion. The Dennys named their country estate Klahanie, Chinook for "out of doors."

Narcissa died in 1900, and Orion later married Helen V. Stewart Cole. They continued to enjoy the retreat at Klahanie. They also became active in the Seattle Yacht Club and Orion had the yacht Halori built for their enjoyment. At the time, the 100-foot vessel was the largest private motor yacht on the Pacific coast.

When Orion died in 1916, he left behind an estate worth $450,000. At this point, his first wife Eva -- now remarried -- reappeared on the scene, demanding $100,000 in alimony payments. Eva died during litigation, but during the lawsuit Helen Denny willed Klahanie to the City of Seattle to become a public park named in memory of her husband.

For the Children

In 1922, O. O. Denny Park was opened for public use, although the Denny residence and two log cabins were locked up. No picnic facilities or restrooms were available, and the beach had not yet been opened to swimming.

Work on the park began in earnest after 1926, when the City of Seattle chose the park as a campsite for Seattle children, "who need to experience life in the green forest." Earlier, land had been set aside near Sand Point for such use -- named Carkeek Park -- but the acquisition of this land in 1926 by the Navy for use as an air facility changed all that.

A new Carkeek Park was chosen in the Blue Ridge neighborhood on Puget Sound, but the parks department felt that the tides and rough waters were not amenable to a children's campground. Instead, the camp buildings of the old Carkeek Park were barged across the lake to O. O. Denny Park. At the same time, the Denny residence was turned into a caretaker unit.

Upgrades

The first permanent caretaker of the park was George W. McQuade, who was hired in 1928. The following year the camp got its first horse, Denver, who had retired from the Seattle Police Department. After a few years of rides by thousands of camp children, veterinarians recommended that the horse be put down. Instead, he was retired a second time into the loving care of McQuade and his wife, so that the children could still visit him.

In 1928, a permit was secured to use the stream flowing through O. O. Denny Park as an irrigation source. When the Great Depression hit in 1929, that work was delayed, but other changes were made throughout the 1930s by various federal works program.

In 1934, the Civilian Conservation Corps cleared the main campsite and added picnic areas, improved the trails throughout the forest, and constructed a bridge across the creek. Two years later, the Works Progress Administration built a seawall and did some restoration on the buildings.

Optimistic Outlook

Seattle children who camped overnight at the park were told to bring a bedroll and a small amount of money for meals. Food was often donated by Seattle storeowners or provided at minimal cost. A camp bus would pick the kids up at local playgrounds in the city and transport them to the park.

A major supporter of Camp Denny was the Seattle Optimist Club. Their first gift to the park, in 1929, was an electric refrigerator. Later they helped with repairs and paid the expenses of underprivileged children throughout the city. They also sponsored many athletic programs and their accompanying awards banquets.

After World War II, more changes came to the park. In 1951, a new stone comfort station was added. In 1954, the Denny residence was torn down and a new caretaker's residence was built in its place. Other buildings were repaired and modernized, and a parking lot was built. Later the beach was sanded.

Transferred Management

In 1968, voters approved the $65 million Forward Thrust Bond issue for Seattle parks and playgrounds. Around the same time, King County was being pressured for more park facilities in the Kirkland/Juanita area, and soon after the City turned over the maintenance and operation of the park to the County.

The City of Seattle continued to own the park, but its days as an overnight campsite for city children were over. Nevertheless, under King County management, O. O. Denny Park became a popular picnic site, and its extensive trail system became a favorite for hikers and nature lovers.

In 2001, a $52 million general fund shortfall in the King County budget led to the closure of 20 parks throughout the county. O. O. Denny Park was one of them. On November 5, 2002, nearby Finn Hill residents voted to manage the park themselves, under an agreement with the City of Seattle. Nearly 70 percent voted in favor of a small property tax increase, one of the most successful endorsements in that year's elections.