The Port of Seattle built Seattle-Tacoma International Airport during World War II to relieve pressure on existing airports such as Seattle’s Boeing Field. Following the war, Sea-Tac quickly established itself as the region’s aviation hub, but it had to undertake major improvements to accommodate newer jet aircraft and steadily increasing numbers of passengers. During the early 1970s, the post-war climb in air travel suddenly stalled, triggering a national aerospace recession known locally as the Boeing Bust. Sea-Tac traffic ultimately recovered, leading the Port in the mid-1970s to pioneer the nation’s most ambitious noise abatement program. Federal deregulation of airlines followed in 1978, sparking a revolution in air service and posing new challenges for the airport.

Clean Air Turbulence

In the late 1960s, the Port of Seattle found itself standing at the intersection of three converging aviation revolutions -- SSTs (supersonic transports), jumbo jets, and short-haul jets -- with an airport that could not handle the needs of the larger planes nor the higher volumes of jet operations (take offs and landings) anticipated in the near future. Passenger traffic had already doubled between 1962 and 1966, and the arrival of Braniff, Eastern, Hughes Air West, Continental, and Pacific Western airlines would bring the number of Sea-Tac’s regular carriers to an even dozen by 1970. Planners predicted that Sea-Tac would reach its maximum capacity a decade ahead of schedule.

This time, the Port vowed not only to pull even with but to leap ahead of the accelerating pace of airline travel. In October 1967, the Port announced a $44 million expansion program, including construction of a second north-south runway set 800 feet west of and parallel to the main runway. By the time ground was broken for this a year later, the cost of airport improvements had risen to $90 million. They would continue to climb as lead architects and engineers at TRA, Inc., and the Port set about re-inventing every aspect of Sea-Tac.

The final plan, adopted in 1968, encased the old terminal inside a dramatic new structure featuring auto access via an upper driveway for arrivals and a lower level for baggage collection and departures. Sky bridges connected the main terminal to the first phase of a multi-deck parking garage for 4,800 vehicles (and a maximum potential capacity of 9,200). This in turn was linked by an internal highway system and new feeder roads to offer the first direct access to Interstate 5.

The terminal itself was expanded to 35 passenger gates with the extension of Concourse C. Satellite terminals were added north and south of the main building, which passengers reached via a pair of subway loops equipped with driverless automatic shuttle trains. Other improvements included new facilities for fuel, air cargo, and aircraft maintenance. Sea-Tac also commissioned an unprecedented $300,000 worth of new works of art to adorn the terminal, supplemented by exhibits borrowed from regional museums. Financed through a combination of Port bonds, chiefly underwritten by airline landing fees and leases, federal grants, and airline investments, the project was well under way by late 1969.

Then the bottom dropped out.

The Boeing Bust

There were no “stall warnings” for the aerospace recession, and no one realized what was happening until it was too late. Passenger traffic had ballooned as travelers switched to air from trains and transoceanic ships. This conversion was already spent by the late 1960s, but airlines still clamored for giant new planes to handle the extrapolated growth. To meet this theoretical demand, Boeing gambled its net worth on the new 747 jumbo jet, which first flew on February 9, 1969. McDonnell-Douglas (created by a 1967 merger) and Lockheed also pushed development of larger “wide-body” aircraft, respectively the DC-10 and L-1011, each of which featured two engines beneath the wings and a third installed in the tail.

Then, inflated airline forecasts collided with inflated prices driven up by the mounting costs of the war in Vietnam, Great Society programs, and decades of complacency in the aerospace industry itself. Air travel plummeted, and airlines tightened their financial seat belts. Boeing was caught in the wind shear, having staked $750 million -- virtually its net worth -- on the 747, which proved too big in a market that was suddenly too small.

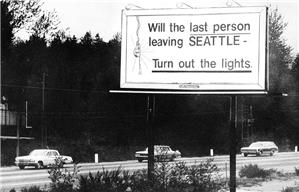

The SST also hit rough air as Congress balked at its rising costs and potential noise and environmental impacts. The project was officially cancelled on March 24, 1971, and Boeing laid off 7,000 workers on that day. During the ensuing two-year “Boeing Bust,” the company laid off more than 60,000 employees, went a billion dollars into the red, and sent the regional economy into a tailspin. In April 1971, a pair of local realtors satirized the mood of doom and gloom by posting a billboard sign near Sea-Tac that asked, “Will the last person leaving Seattle turn out the lights?” Nobody laughed.

Through it all, the Port kept rebuilding and expanding Sea-Tac according to its 1968 plan. The schedule survived angry protests from African-American contractors and construction workers who felt excluded from the project (this was quickly remedied through stronger affirmative action policies). The cost of airport expansion had risen to $175 million by 1973, driven in large part by the hyperinflation of the period. Despite these challenges, The Port unveiled its new terminals in July to general praise, and traffic rebounded to 5.2 million passengers that year.

Unfriendly Skies

Amid the political turmoil of the late 1960s, “skyjackings” and terrorist acts involving passenger aircraft began to surge. Sea-Tac would make headlines with one such incident on the stormy night of November 24, 1971.

A passenger listed as “Dan Cooper” -- later incorrectly but permanently dubbed “D.B. Cooper” -- boarded a Northwest Orient 727 at Portland, Oregon, for the Thanksgiving eve flight to Seattle. He passed a note to a flight attendant informing her that he had a bomb in his brief case that he would set off unless his demands were met. These consisted of four parachutes and $200,000 in twenties, which were put on the plane at Sea-Tac. The plane took off again for Mexico, and the skyjacker leapt from its rear passenger stairway over southern Washington. He was never heard from again, although some of his loot turned up nine years later along the banks of the Columbia River.

Thanks to this and other incidents around the world, federal law mandated tighter security for airports in 1972 and the Port responded by establishing a professional police force for Sea-Tac. The following year, Sea-Tac more than doubled its police force to 83 officers while airlines installed and staffed X-ray and metal detector checks at departure gates.

Total airline operations dipped by nearly 9 percent in 1970 from a peak of nearly 166,000 landings and takeoffs the previous year, and then began a slow climb back. Total numbers disguised the growth in airliner operations, which set a record of 115,445 in 1973 while “general” aviation activity by small private aircraft leveled off at around 23,000 annual operations. This steady increase in airline traffic was all the more remarkable because it absorbed the decline of military passengers with the phasing out of American involvement in Vietnam and, later, the shock of the OPEC oil embargo in 1973.

Noise Becomes an Issue

Some of the people living closest to Sea-Tac did not celebrate the airport’s renewed activity. In fall 1971, a number of nearby residents organized “The Zone Three Committee,” named for the FAA-designated area stretching six miles north and south of Sea-Tac in which aircraft noise reached its highest levels. Nearly 7,000 area residents signed a petition demanding that the Port buy out the 2,000-plus households within Zone Three to establish a buffer zone.

Other residents sued the Port for lost property value, cracked windows and plaster, and frayed nerves. The Port had paid out $1.2 million by 1973, and 300 individual suits were still in the courts. They were joined by the Highline School District, which claimed that airport noise had caused $10.7 million in damages to school facilities and operations. Clearly, a comprehensive solution was needed.

With the active support and funding of the FAA, the Port joined with the government of King County to launch the “Seattle-Tacoma International Airport and Vicinity Master Plan Project.” Work began in January 1973 and took 18 months and more than $650,000 to prepare what became known as the “Sea-Tac Communities Plan” to address not only noise, but broader airport impacts on traffic, water and air quality, and land use patterns.

With adoption of the Sea-Tac Communities Plan in 1976, the Port became the first airport operator in the nation to establish a noise buffer around its facility by purchasing hundreds of homes as well as school buildings, and, later, by sound-proofing hundreds more. These innovations were honored with the American Institute of Planners’ Meritorious Program Award in 1978. The Port’s development of a public park on 420 acres of vacated land north of the airport later won the Federal Aviation Administration’s Aviation Environment Award.

Although the plan could not satisfy every airport critic, it provided a blueprint to guide the airport’s development impacts through the balance of the twentieth century, during which traffic at Sea-Tac was expected to quadruple to 20 million annual passengers. This prospect was good news for the sizable business district of office buildings, restaurants, and hotels housing more than 2,000 guest rooms that had sprung up around the airport. Most were concentrated along “the strip” of Pacific Highway South (U.S. 99) bordering the airport on the east (renamed International Boulevard by the City of SeaTac after its incorporation in 1990). Airport-related consumer spending reached nearly $40 million annually by the early 1970s. The airlines themselves spent more that $300 million a year at Sea-Tac and supported an airport workforce of more than 7,000 persons.

Free Fall

The “Era of Deregulation” is usually associated with President Ronald Reagan (1911-2004), but the most dramatic reforms were actually undertaken by his predecessor, Jimmy Carter (b. 1924). During his single term, Carter loosened the federal reins on interstate trucking and banking as well as on the airlines. The latter action was approved by Congress in 1978 at the strong urging of the airline industry, which was trying to absorb massive increases in fuel prices -- which skyrocketed by 1000 percent in 1974 alone -- and to cope with economic “stagflation” while fending off stiffening competition from foreign-flag carriers on international routes.

The direct effect of deregulation was to allow airlines to establish their own domestic routes as they chose (international routes still required federal approval) and set their own fares. The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 also released them from requirements to serve smaller, unprofitable destinations. The theory was that greater competition would help erase the legacy of inefficient practices accumulated over 65 years of federal protection and that it would deliver lower prices to consumers.

Few airlines, however, were prepared for the bare-knuckle combat of unrefereed competition that followed. It didn’t help that a national recession coincided with the first years of deregulation.

Fare wars broke out on major routes, sometimes pushing prices to “loss-leader” lows, as older airlines tried to protect their market share from start-up lines that were not saddled with their debts and institutional traditions. At the same time, fares for travel to more remote destinations shot out of sight, and smaller cities faced the prospect of losing most or all of their accustomed air service.

The squeeze on operating costs was felt first and most by airline workers -- mechanics, attendants, pilots, and office staff -- who saw decades of union protection and good wages evaporate in “give-back” contracts. Airplane builders were similarly unprepared. Boeing had already committed itself to a pair of new twin-engine planes, the narrow-body 757 and wide-body 767, as fuel-efficient replacements for aging 707s on traditional routes, but with deregulation there was no longer such a thing as a traditional route. The timing of the two planes’ first flights in 1981 and 1982 could not have been worse, but the aircraft later redeemed themselves by proving the safety of large twin-engine jets on long flights over the ocean.

After deregulation, airlines shifted to “hub and spoke” arrangements in which smaller aircraft fed into major airports, connected in turn by service with high-capacity planes. Boeing’s 737 and 747 proved to be perfect work mates in this system. Feeder routes also gave McDonnell-Douglas an expanded market for the DC-9 and its MD-80 descendants. Both it and Lockheed ended production of their wide-body jets in the early 1980s, while the European Airbus consortium entered the field with a brand new family of advanced, fuel-efficient aircraft.

But it was the airlines themselves that endured the roughest ride. Before deregulation, America was served by 36 airlines; by 1984 there were 120. In between, 117 airlines filed for bankruptcy -- some more than once -- and aviation mainstays such as Pan Am, TWA, and Eastern were humbled or driven into extinction.

The effects of this aerial combat were felt on the ground at Sea-Tac. Passenger traffic had risen to 9.8 million by 1979. The following year, it plummeted by 600,000, and sank even lower in 1981. Airport director Don Shay wisely chose this year to retire. He had worked at Sea-Tac since the days of the first airline service in 1947, but the industry that he and his airport had grown up with was no longer recognizable.

To go to Part 4, click "Next Feature"