This essay surveys the development of Seattle’s South Lake Union and Cascade communities from 1854 to 2003, with emphasis on visions for its future including Virgil Bogue’s 1911 Plan of Seattle, the 1972 Bay Freeway, the 1995-1996 Seattle Commons proposals, and Paul Allen’s (1953-2018) efforts to create a new community centered on biotechnology. It was published in The Seattle Times on June 8, 2003.

The Dream of a Ship Canal

On July 4, 1854, the hundred or so citizens of the new town of Seattle collected on the south shore of what their Duwamish neighbors called meman hartshu, or tenas chuck in the Chinook trading jargon. Thomas Mercer, who had laid claim to the area around this “little lake” along with newlyweds David Denny and Louisa Boren, addressed the community’s first Independence Day picnic.

First, Mercer proposed that they rename the larger lake to the east, called hyas chuck in Chinook and Lake Geneva by a romantic few, “Lake Washington” to honor the nation’s first president. Then he advocated that the smaller lake be named “Lake Union” because it was only a matter of time before a great canal would unite it with Puget Sound on the west and Lake Washington on the east.

The crowd roared its approval and map makers quickly adopted Mercer’s proposal. The ship canal, however, took another 80 years to complete. It was the first great notion inspired by Lake Union, but hardly the last, and offered a cautionary lesson in patience for the dreamers and developers who would follow Thomas Mercer.

Lake Union as a Backwater

Back in 1854, Lake Union was the backwater of a backwater town. A natural dam at Montlake sealed it off from the higher Lake Washington, while only a tiny stream through Fremont drained it into Salmon Bay. The discovery of coal near Issaquah also fueled new interest in the lake, but it was no easy matter getting it from Lake Washington barges and wagons over “Portage Bay” to Lake Union and then overland to Elliott Bay.

The Seattle Coal and Transportation Company simplified the problem in 1872 by building a narrow-gauge railroad -- Seattle’s first -- from the south shore of Lake Union to present-day Pike Street. To avoid the obstacle of Denny Hill (since flattened) the line followed a diagonal route along today’s Westlake Avenue to Pike, then turned west to end in a giant coal dock.

After completion of a new southern railway to Seattle’s waterfront, the coal line and its Pike Street dock were abandoned in 1877. Mayor Gideon Weed proposed paving its Westlake route, but this was not accomplished for another 30 years. In her memoir of Pig-tail Days in Old Seattle, Sophie Frye Bass recalled taking childhood walks “down the grade,” which was “lined with all kinds of shrubs -- wild roses, red currant and squaw berry bushes,” and encountering elderly Duwamish men and women who still dwelled on the lake’s southern shore.

The Developers

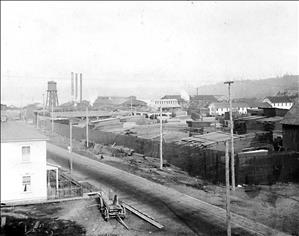

Development accelerated after David Denny built the Western Mill in 1882, near the site of today’s Naval Reserve Center, and cut a weir at Montlake to float logs between the lakes. Homes soon began to appear on the Lake Union’s south shore, ranging from the ornate Queen Anne-style mansion built by Margaret Pontius in 1889 (which served as the “Mother Ryther Home” for orphans from 1905 to 1920) to humble worker's cottages.

The latter housed a growing number of immigrants from Scandinavia, Greece, Russia, and America’s own teeming East, attracted by jobs in Seattle’s burgeoning mills and on its bustling docks. Beginning in 1894, their children attended Cascade School -- which finally gave the neighborhood a name -- and families worshipped on Sundays at St. Dimitrios, St. Spiridon, and Immanuel Lutheran as the “Old World” settled into a new way of life.

Thanks to the introduction of privately operated cable cars and electric streetcars in the 1880s, Seattle’s population began to push northward to Lake Union and beyond. Eager to link downtown Seattle to the burgeoning towns and suburbs north of Lake Union, the city held a “build off” in October 1890 between companies competing for the coveted rail transit franchise.

While cable car operators opted to follow the established street grid, entrepreneur L. H. Griffith quietly bought up the route of the old Lake Union coal railroad. His electric streetcars were running along future Westlake Avenue just five days after construction began. What was then called Rollin Street was finally paved for wagon and auto traffic in 1906.

The Visionaries

The first decades of the twentieth century in Seattle were dominated by skilled and supremely self-confident technocrats such as city engineer R. H. Thomson, landscape architect John C. Olmsted, and urban planner Virgil Bogue. Each had his own vision for Lake Union and its southern shore.

Thomson leveled Denny Hill, and regraded 9th Avenue in 1911 to “funnel” development toward the lake. Olmsted, hired in 1903 to plan the city’s park system, regarded Lake Union an industrial district but proposed a small park on the lake's south shore. The neighborhood contented itself with Denny Park (a former cemetery) donated back in 1884 by David Denny.

Virgil Bogue’s 1911 “Plan of Seattle” placed a towering “Central Station” on the lake’s south shore, with vast rail yards, commuter ferry docks, and the terminal for a rapid transit tunnel linking Seattle to Kirkland beneath Lake Washington. Bogue’s ideas were defeated by downtown interests and by voters in 1912.

Another technocratic titan, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers commandant Hiram M. Chittenden, finally transformed the lake in 1917 by breaching Montlake, dredging Fremont, and building the ship canal locks that now bear his name. Work on the canal and its five drawbridges was not declared complete until 1934 -- 80 years after Thomas Mercer’s Fourth of July picnic epiphany.

Commercial Developments

The locks elevated Lake Union’s importance for both maritime and landside commerce. Dry docks, marinas, machine shops, mills, and factories jostled for space with its old squatter houseboats and worker cottages. Henry Ford built an assembly plant for Model Ts (now Shurgard’s headquarters), The Seattle Times relocated from downtown, giant laundries and gaudy auto dealerships sprang up on once vacant lots. On the eve of World War II, the Navy built its Art Moderne reserve center on the former site of Denny’s Western Mill, and after V-J Day, teacher-turned-banker Robert Handy picked the sleepy neighborhood to house what would become PEMCO Financial Services.

Meanwhile, the “Aurora Speedway,” sliced through Woodland Park, soared across the ship canal, and terminated abruptly at Broad and Denny in 1932, spilling traffic on to downtown streets. The Alaskan Way Viaduct opened in 1953, soon followed by trenches for Mercer and Broad streets. Then Interstate 5 severed Lake Union from its western Capitol Hill neighbors in the early 1960s and created a permanent traffic jam on Mercer and Valley streets.

Not far away, the upland homestead where Louisa Denny had once tended sweetbriar roses sprouted a Space Needle, Coliseum, and Science Center in 1962 -- linked to Westlake Mall (now Center) by a futuristic trolley called a “monorail.” After the Century 21 World’s Fair crowds departed, south Lake Union was left with the Mercer Mess. Mayor Wes Uhlman proposed to tidy things up in 1972 with a “Bay Freeway” viaduct linking I-5 and 99, but voters were in an anti-highway mood.

South Lake Union abided in obscurity. The wandering Wawona, last of the great Pacific cod and lumber schooners, found a final berth there, and wooden boat artisans led by Dick Wagner moored nearby. Young bohemians rediscovered the Cascade neighborhood’s Old World charms, and its cheap land nurtured emerging biotech enterprises such as the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and Zymogenetics (housed in City Light’s 1914 steam plant).

The Commons Crusade

Then Seattle Times columnist John Hinterberger had a new Mercer-like revelation on the road to Lake Union, where he saw virgin land for a great park, boulevards, “whispering firs and salmon runs.” Encouraged by architect Fred Bassetti, Hinterberger published his “absurd” but “delicious” vision in April 1991.

This planted the seed for the energetic civic enterprise that became known as the “Seattle Commons,” led by a young developer named Joel Horn and backed by a “who’s who” of both graying Establishmentarians and Baby Boomer activists, including a billionaire named Paul Allen. The project’s vision of a vast 60-acre civic lawn framed by high-tech laboratories, condos, bistros, and tree-lined promenades offered a blueprint for transforming a dowdy hodgepodge of working-class houses and businesses into a gleaming “urban village.”

Without irony, Commons supporters invoked Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann, who smashed through the medieval streets and tenements of nineteenth century Paris to create today’s great boulevards and parks. All very lovely -- unless your home or business happened to be in the way. Haussmann’s wrecking crews were backed by an Emperor, but things work a little differently in the People’s Republic of Seattle. After lively debates, voters rejected Commons levies in 1995 and 1996.

The Commons crusade disbanded, but many of its better ideas survived. The city got serious about a park and maritime heritage center at South Lake Union, and it negotiated a community plan with the Cascade neighborhood’s residents and business owners. Paul Allen, who had purchased 13 acres “in trust” for the Commons quietly supplemented his holdings to create a critical mass of properties for coordinated development as a biotech research center and residential community. Most recently, Mayor Greg Nickels (b. 1955) proposed running streetcars up and down Westlake -- for which it had been created more than a century ago.

Commons Lite? Perhaps, but also a more patient, methodical, and evolutionary approach to an area that has seen more than its fair share of grand visions and that has outlived most visionaries. As Thomas Mercer learned, dreams take a while to germinate in the fields south of Lake Union.