On July 1, 1893, the City of Tacoma buys the drinking water and electrical power properties of Tacoma Light and Water Co. from Charles B. Wright (1822-1898) for $1.75 million. The deal is not a good one for the City, but it places Tacoma at the vanguard of the municipal ownership movement in Washington and in the nation.

In 1884, Northern Pacific Railroad President Charles Wright organized Tacoma Light and Water and acquired a franchise from the City Council to provide drinking water and electricity in Tacoma. This put competitor and City Council member John E. Burns out of business. In the words of historian Murray Morgan, Burns embarked on a campaign against “the Railroad Crowd, Philadelphia Nabobs, and the Dogfish Aristocracy, finding them impediments to civic progress, enemies of the working man, and dangers to the purity of drinking water” (Morgan, 315).

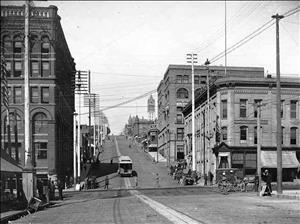

When railroad builder Nelson Bennett purchased the Tacoma Hotel from the Tacoma Land Co. (a subsidiary of the Northern Pacific), his water bill jumped from $75 a month to $502. Nelson complained to NP President Wright in Philadelphia. Wright then jacked up Bennett’s home water bill too. Bennett went to the City Council, which was already concerned about cases of typhoid in the city. Drinking water flowed to the city in open flumes to humans and farm animals. Wright threatened to stop spending money on the water system and suggested that the City might like to buy it.

Wright and the Council negotiated a $1.75 million purchase price for the water and electrical systems. The voters approved the deal (with a margin of 104 votes in a three-fifths majority) on April 11, 1893. Tacoma soon learned that it had been the victim of some sharp dealings. The gas works was not included and Spanaway Lake was contaminated. The flumes were falling apart. One dam had failed. Other sources of fresh water turned out to be in private hands or smaller than advertised. The electrical plant was inadequate and in poor repair. The City had gone $300,000 over its debt limit so there was no money for repairs or improvements. After years of litigation, Wright’s estate paid the City $125,000 in fees and damages.

Dissatisfaction with privately owned utilities was widespread and many other cities also entered the utility business to obtain lower rates and better service.