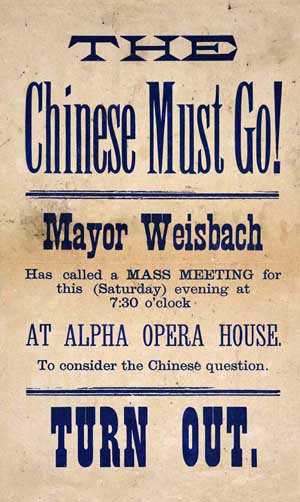

On November 3, 1885, a mob, including many of Tacoma's leading citizens, marches on the city's Chinese community and forces everyone out of their houses and out of town. Tacoma mayor Jacob Robert Weisbach has deemed the Chinese "a curse" and a "filthy horde." The Tacoma Ledger and its editor Jack Comerford, the carpenters' union, and many workers and business people have spewed racist rhetoric against the Chinese for months. Mass meetings inflame the hatred and the few dissenters, most notably Ezra Meeker and the Reverend W. D. McFarland, are ineffectual against it. The Chinese community has been given a deadline to get out by November 3. In reaction to the threats, about 150 frightened Chinese persons leave Tacoma before the deadline. The mob herds another 200 out on November 3. They lose their homes and most of their possessions, and they will not return. More than a century later, in 1993, the Tacoma City Council will pass a resolution to make amends and to apologize for the former city leaders' actions.

Building America's Railroads

Many Chinese had come to the Pacific Northwest in the 1870s and 1880s to work on the railroad. About two thirds of the laborers -- some 15,000 men across several states -- who laid tracks for the Western Division of the Northern Pacific were Chinese. Across the country, the anti-Chinese movement gained momentum in the context of an economic downturn after the railroad was built. The labor movement, particularly the Knights of Labor, took a hard line against what they called “coolie” labor – men who “were willing” to work for lower wages. In fact of course Chinese laborers worked for as much as they could get and no American labor organization invited them to join the movement to improve wages and working conditions.

In Tacoma, the Chinese community was somewhat transient, with laborers coming to town looking for work, staying for a while, then moving on. Most Chinese residents lived on the waterfront along the Northern Pacific tracks on land leased from the railroad. Chinese Tacomans worked as waiters, as servants, and in the logging industry. They did the town’s laundry and collected its garbage. A few entered business as labor contractors or merchants, at first selling goods to fellow Asians, and then to the whites in town. They fished and grew vegetables in large gardens and raised pigs.

The more established Chinese had been in Tacoma as long or longer than the anti-Chinese mayor (Weisbach was a German immigrant who had arrived in the 1870s). Longterm residents of Tacoma included merchants and labor contractors Sing Lee (arrived in Tacoma 1872), Kwok Sue (arrived 1873), Lum May (opened a store in 1874), and How Lung, who went into business in 1875.

A Mob in Raincoats

Mass meetings, secret meetings, threats, and verbal abuse in person and printed in the newspaper led to the order delivered to the Chinese community that they must get out by November 3. About 150 Chinese left before the deadline, taking the train south to Portland, or boarding the steamer Southern Chief for Victoria. Goon Gau wired Territorial Governor Watson Squire: “I am notified that at three p.m. tomorrow a mob will remove me and destroy my goods. I want protection. Can I have it?” (Murray Morgan, 244). The governor did not respond.

On November 3, “a mob in raincoats,” in the words of Murray Morgan, marched to the Chinese section of town. They broke open doors and ordered people out. The Chinese were frightened, some were crying. Some asked for more time to gather their possessions. The mob arrived at How Lung’s store and kicked off the door. They pulled people, including his wife, out of the building. They pointed pistols, but did not shoot.

At other houses men broke open doors, smashed windows, and stole possessions as they rounded the people up. They marched them through the mud to waiting delivery wagons. This rain-drenched, weeping, terrified procession, some walking and some riding, proceeded to the Northern Pacific station at Lake View. The stationmaster sold 77 tickets to the morning train to Portland to those who could afford them. Around 3 in the morning a freight train stopped at the station and took on all those who could not afford tickets.

Excepting a very few house servants, the Chinese in Tacoma were gone. The mob burned their houses to the ground. They lost everything but their lives, and they never returned.

The perpetrators were indicted, put on a train for Vancouver, and went before Judge Hoyt, who set them free on bail. They returned to Tacoma as heroes in a welcoming parade. Eventually the trial was transferred to Tacoma, and all the indictments were dropped.

In 1993, the Tacoma City Council passed a resolution to make amends, apologize for the former city leaders' treatment and expulsion, and appointed a citizens committee that became the Reconciliation Foundation, with its goal to "promote peace and harmony in our multicultural community."