Chief Seattle, or si?al in his native Lushootseed language, led the Duwamish and Suquamish Tribes as the first Euro-American settlers arrived in the greater Seattle area in the 1850s. Baptized Noah by Catholic missionaries, Seattle was regarded as a "firm friend of the Whites," who named the region's future central city in his honor. He was a respected leader among Salish tribes, signing the Point Elliott (Mukilteo) Treaty of 1855, which relinquished tribal claims to most of the area, and opposing Native American attempts to dislodge settlers during the "Indian Wars" of 1855-1856. Chief Seattle retired to the Suquamish Reservation at Port Madison, and died there on June 7, 1866.

The Native American leader whose name was given to Puget Sound's largest city was born on the Kitsap peninsula some time in the 1780s. Historian Clarence Bagley records his father's name as Schweabe, of the Suquamish Tribe and his Duwamish mother's name as Scholitza. When he was old enough to receive an adult name, their son was called si?al, which has been rendered into English with fair accuracy as Seattle.

Pronouncing Chief Seattle's Name

The often heard "Sealth," rhyming with "wealth" is incorrect. The original name continues to be passed down among si?al's (Seattle's) descendants: It has two syllables and there is no th sound in the Puget Sound Salish (Lushootseed) language. The spelling Sealth on the leader's 1890 grave marker was probably an effort to render the pronunciation more correctly. The result of this effort toward accuracy has been the spread of a completely inaccurate version of the Chief's name.

Editor's Note: The Lushootseed language is written using the International Phonetic Alphabet, and in it Chief Seattle's name has two marks not found in English. One mark looks like a question mark without the dot at the end. This is a glottal stop as in "Uh oh." Chief Seattle's name is sometimes written Se'ahl and the ' is another type of glottal stop. (The mistaken "Sealth" notion has eliminated this sound, which the word Seattle, pronounced See-attle, retains.) No one language contains all the phonemes (individual language sounds) found in all human languages, and the end-sound of Seattle does not occur in English. In Seattle's name, this sound has shifted, according to Skagit elder and Lushootseed language expert Vi Hilbert (1918-2008). Traditionally it had a "glottalized barred lambda" at the end, an explosive sound. Later the pronunciation shifted to a lateral "l," a sound something like "alsh" and represented by a mark that looks like an l but is crossed horizontally at the center. However, according to Vi Hilbert, the proper pronunciation is with the traditional glottalized barred lambda. Play the audio clip in the left-hand column to hear Skagit elder Vi Hilbert, introduced by her longtime student and chronicler Janet Yoder, pronounce Chief Seattle's name and explain the pronunciation.

Historic Transformations

Chief Seattle's life spanned a time of incredible change for his people and the Puget Sound region. Tradition tells us that, as a boy, he was in one of the canoes that met the first Europeans to enter Puget Sound. The sloop-of-war Discovery and the armed tender Chatham, under the command of Captain George Vancouver (1758-1798), spent a week during May 1792, in the waters south of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, making charts for future use, naming landmarks and waterways, and making observations of the local inhabitants and their villages. No doubt the local inhabitants carefully observed these newcomers, and wondered what their presence foretold.

More than 40 years later the first European settlement was established on the sound by the Hudson's Bay Company at the mouth of Sequallitchew Creek (near present-day Olympia). Records indicate that Seattle was among the many Native Americans who came to Fort Nisqually to trade pelts, especially beaver and sea otter, for sheep-wool blankets and other imported goods. It may be that these encounters began Seattle's life-long fascination with the trappings of European and European American culture, and his respect for the power and ambition of the immigrants who were claiming his land.

Noble Birth, Intelligence, Courage

As he matured, his own people increasingly recognized Seattle as a capable leader. His parents' ancestry meant that he was related and recognized on both sides of Elliott Bay and up the Duwamish River. He was si?ab (see-ahb) or of noble birth, a necessity for major leadership in the stratified society of Puget Sound Salish culture. (Women, commoners, or trusted slaves could suggest ideas when a village or gathering debated a course of action, but were not selected as leaders.)

Seattle impressed his contemporaries with his intelligence and courage. One story indicates that he became a headman or chief because of his leadership during an attack by warriors coming down the White River, planning to attack the Suquamish. Seattle, it is said, had a large tree cut down just downstream of a bend in the river (either the Duwamish or Black River). The enemy canoes rounded the bend and crashed into the barrier, exposing their passengers to attack by Seattle's men on shore.

Such a success would have greatly enhanced Seattle's role as a leader, as would his abilities as a diplomat and orator. Family members affirm that one of si?al's spirit powers was thunder, allowing his voice to be heard from a great distance, and at least one American writer admired his presence in a public gathering. Seattle's predecessor as head of the Suquamish, Calqab (tsahl-kub), had been admired as a peacekeeper, forbidding revenge raids against the Skykomish. Calqab's predecessor qeCap (Kitsap) was honored as a war leader.

Known for a City and a Speech

By the time Euro-American settlers began arriving in the area, Seattle had been accepted as headman or chief by most of the Native Americans from the Cedar River and Shilshole Bay to Bainbridge Island and Port Madison. He was baptized by Catholic missionaries and welcomed the Collins and Denny parties respectively at the mouth of the Duwamish and at Alki (proper pronunciation AL-kee) in the fall of 1852. In 1852, Seattle reputedly persuaded David S. "Doc" Maynard (1808-1873) to move his general store from Olympia, to which Seattle often canoed for supplies, to the village of Duwumps. Maynard named his new store the "Seattle Exchange" and convinced settlers to rename their town after the chief when they filed the first plats on May 23, 1853.

Aside from the civic appropriation of his name and his later leadership in the signing the Treaty of Point Elliott, Seattle's most enduring legacy may be a speech attributed to him by pioneer Dr. Henry A. Smith (1830-1915), who published it "from notes" in the Seattle Sunday Star of October 29, 1887 -- nearly 35 years after it was supposedly given. Although no contemporary accounts survive, Smith says the Chief addressed his remarks to newly appointed Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens (1818-1862) upon his first visit to Seattle in January 1854. As reconstructed by Smith, Seattle made an eloquent plea, both melancholy and cautionary, to Stevens and other settlers: "Let him [the white man] be just and kindly with my people, for the dead are not altogether powerless." Later versions of Smith's translation were adopted as manifestoes of environmentalism and Native American rights.

The Point Elliott Treaty

Within a year of his arrival, Stevens summoned tribal leaders to a treaty conference at Point Elliott (now Mukilteo) on January 21-23, 1855. Seattle was the first tribal chief to place his mark on a document that ceded ownership of most of the Puget Sound basin. (Other signers were Patkanim of the Snoqualmies, Goliah of the Skagits, and Chowitsoot of the Lummis). The treaties promised that some lands would stay in Native American ownership (reservations), and that education, health care, money, and other payments would be made.

Both sides had difficulty understanding each other's ideas since all conversation had to be translated twice -- from Lushootseed (Puget Sound Salish) to Chinook Jargon, a limited trade language, then from Chinook to English, and the same process in reverse. Legal enforcement of treaty rights remains a source of litigation and political controversy to the present day (1999).

The Battle of Seattle

The treaties of 1854-55 were not ratified by Congress for more than three years, and many of the benefits for tribes were decreased, delayed, or disputed. Many tribal leaders were so dissatisfied with the results that they took up arms to force a better agreement, or the expulsion of whites from their traditional lands. By late 1855, European American settlers in the Puget Sound region were in danger of armed attack.

Even though the treaties did not provide all that Seattle expected (there was no separate reservation for his Duwamish relatives, for example), he kept his promise and did not fight. During the "Treaty War" of 1856, including the brief, ironically named "Battle of Seattle" on January 26, 1856, Chief Seattle stayed across the sound at Port Madison and induced as many of his people as he could to come with him. He also warned white friends of impending violence when he could.

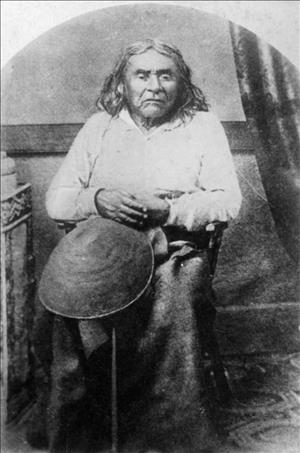

When the fighting was over and Seattle began to swell with newcomers, most European Americans took little notice of si?al or his people. One story tells of a 10-year-old girl who pushed the old Chief off a board sidewalk -- everyone knew that Indians were supposed to get out of the way of white people. He continued to visit old friends in the city from time to time, and once, about a year before his death, went into a photographer's studio to have his portrait made. For the most part, Seattle stayed home, dealing with the problems of overcrowding, disease, and traveling whiskey sellers on the reservation.

"The Dead Are Not Altogether Powerless"

His people continued to show him respect. In 1954, Suquamish elder Wilson George recalled that his mother had taken food to the elderly si?al at his home, Old Man House, on the beach at Suquamish, and that Sam Snyder brought him fresh water every day. Seattle was recognized as Chief until his death on June 7, 1866.

Noah Seattle died of a severe fever and was buried with Catholic and native rites in the reservation cemetery at Suquamish, dressed in European American clothing (provided by the Indian Agent). Seattle's good friend George Meigs shut down his sawmill so that he and his Native American workers could attend. One of the Chief's last requests was that Meigs shake hands with him in his coffin as a farewell.

Sadly, no Puget Sound newspaper covered the funeral, and there is no indication that any of the founding pioneers of his namesake city came to pay last respects to Seattle, Chief of the Duwamish and Suquamish (however, Bagley says "hundreds" of whites attended). Si?al's daughter, Kikisoblu or Angeline, lived in the city until her death in 1896, earning her living as a laundress. His son, Jim Seattle, was Chief for a time, but he "talked rough to the people." He was replaced, by the ancient method of group opinion, by Chief Jacob (Wahelchu?).

In about 1890, a group of history-minded Seattleites placed the stone marker seen today at Seattle's grave on the Port Madison Reservation. One side reads "Seattle, Chief of the Suquamps and Allied Tribes, Died June 7, 1866. Firm Friend of the Whites, and For Him the City of Seattle was Named by Its Founders." The reverse reads, "Baptismal Name: Noah Sealth, Age probably 80 years." Seattle is also memorialized in his namesake city with a Pioneer Square bronze bust (1909) and a Denny Regrade statue (1912), both sculpted by James A. Wehn.