On January 26, 1700, at about 9:00 p.m. Pacific Standard Time a gigantic earthquake occurs 60 to 70 miles off the Pacific Northwest coast. The quake violently shakes the ground for three to five minutes and is felt along the coastal interior of the Pacific Northwest including all counties in present-day Western Washington. A tsunami forms, reaching about 33 feet high along the Washington coast, travels across the Pacific Ocean and hits the east coast of Japan. Japanese sources document this earthquake, which is the earliest documented historical event in Western Washington. Other evidence includes drowned groves of red cedars and Sitka spruces in the Pacific Northwest. Indian legends corroborate the cataclysmic occurrence.

The Earth Moves

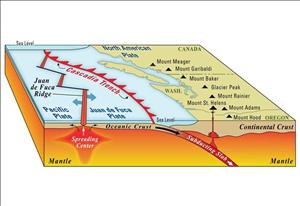

The earthquake ruptured what is known as the Cascadia subduction zone -- the area of overlap between two of the tectonic plates that make up the earth's surface, the Juan de Fuca plate and the North American plate. The Cascadia subduction zone extends from Vancouver Island, British Columbia (about 49 degrees 30 minutes North Latitude) south to Cape Mendocino in northern California (about 40 degrees North Latitude). The earthquake dropped the entire Pacific Northwest ocean coastline three to six feet. The tsunami, up to 33 feet high, inundated the ocean coast.

This was one of the largest earthquakes the Pacific Northwest has ever had. It compares with two disastrous earthquakes: the March 27, 1964 Alaska earthquake, which measured 9.2 moment magnitude, and the May 21-22, 1960 Chile earthquake, which measured 9.5 moment magnitude.

Japan's Orphan Tsunami

The tsunami traveled across the Pacific Ocean for some 10 hours and at midnight on January 27, 1700, local time, it hit the east coast of Honshu Island, the main island of Japan. Four contemporary Japanese sources describe the 6- to 10-foot-high tsunami and five of the towns it inundated along 600 miles of the Honshu Island coast.

The Japanese call the tsunami their "orphan tsunami" because no earthquake felt in Japan accompanied it.

Seawater-drowned Groves and Indian Legends

Drowned groves of trees occur in several places in the Pacific Northwest. They have been dated within 30 or 40 years of the known date of the earthquake, which is suggestive but not conclusive. However, carbon dating of the tree rings of a seawater-drowned red cedar near the Copalis River in Grays Harbor County show that the tree died between August 1699 and May 1700, that is, in the same earthquake.

Native Americans witnessed this earth-shattering event. Ruth Ludwin, a University of Washington geophysics professor has searched for Indian legends that could refer to the event. She has found many similar tales of plains becoming oceans, mudslides, and the like.

The Hoh Indians of the Forks area of the Olympic Peninsula tell of an enormous "shaking, jumping and trembling of the earth ..." (The Seattle Times). The Makah who live on Neah Bay at the northwest tip of the continent have a version in which a whale is delivered to the mouth of a river and saves the people who had been starving. This legend forms the basis for the tribe's whale hunt.