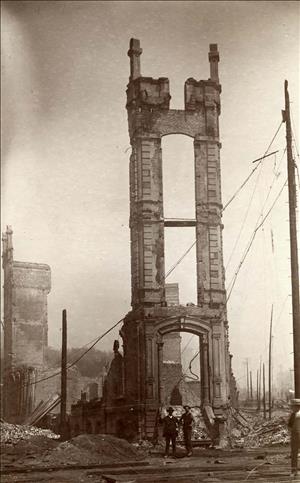

At about 2:30 p.m. on June 6, 1889, a pot of glue bursts into flames in Victor Clairmont's basement cabinet shop at the corner of Front (1st Avenue) and Madison streets in Seattle. Efforts to contain the fire fail and it soon engulfs the wood-frame building. Thanks to a dry spring and a brisk wind, the flames spread quickly, and volunteer firefighters tap out the town's inadequate, privately-owned watermains. By sunset, some 64 acres lie in smoldering ruins. This event is known as the Great Seattle Fire.

Devastation, but no Fatalities

As Northwest historian Paul Dorpat would write years later, "It takes a conspiracy of coincidences to turn an ordinary fire into a great one. Mid-afternoon, June 6, 1889, Seattle was ready with a heat wave, a fanning wind from the north, its fire chief out of town, next to no water pressure, a business district constructed of clapboard, and an upset pot of glue." ("Now & Then ..."). After igniting in Clairmont's shop, the blaze spread in all directions, racing unseen through basements and under planked streets and sidewalks before breaking into the open. Within a few hours, much of Seattle's commercial core and waterfront was destroyed.

Many histories of Seattle erroneously ascribed the fire's start to James McGough's paint shop on the floor above Clairmont's workshop at Front and Madison, based on initial newspaper reports. McGough protested his innocence, and on June 21, 1889, the Post-Intelligencer published a correction and detailed interview with John Back, who worked in Clairmont's shop and admitted to sparking the blaze by throwing cold water on the overheated glue pot. Despite this, the error was repeated by historians and journalists for nearly a century, until historian James Warren noticed the correction and, in his 1989 monograph The Day Seattle Burned, shifted the point of origin to Clairmont's shop.

After the fire, insurance investigators charged the city with having both an inadequate water supply and an inadequate fire department. Firefighters were described as being poorly trained, and most of them, including their chief, quit in disgust at the charges. In response, the city authorized the creation of a paid, professional fire department, which was passed by ordinance on October 17, 1889. Three days later, 32 men were hired.

Many Seattleites lost businesses. Among them were African American businesses, including an employment agency, a hotel, a restaurant, two barbershops, a boot and shoe making shop, and a real estate firm. Mayor Robert Moran rallied Seattle's citizens to rebuild -- with brick and stone this time. The result survives today as Pioneer Square.