During the early morning hours of March 1, 1910, an avalanche roars down Windy Mountain near Stevens Pass in the Cascade Mountains, taking with it two Great Northern trains and 96 victims. This is one of the worst train disasters in U.S. history and the worst natural disaster (with the greatest number of fatalities) in Washington.

Inching Toward Disaster

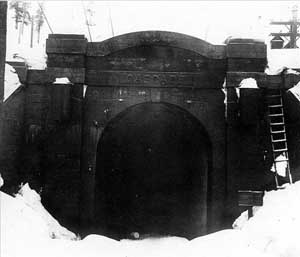

On February 23, 1910, after a snow delay at the east Cascade Mountains town of Leavenworth, two Great Northern trains, the Spokane Local passenger train No. 25 and Fast Mail train No. 27, proceeded westbound toward Puget Sound. There were five or six steam and electric engines, 15 boxcars, passenger cars, and sleepers. The trains had passed through the Cascade Tunnel from the east to the west side of the mountains when snow and avalanches forced them to stop near Wellington, in King County. Wellington was a small town populated almost entirely with Great Northern railway employees.

The train stopped under the peak of Windy Mountain, above Tye Creek. Heavy snowfall and avalanches made it impossible for train crews to clear the tracks. For six days, the trains waited in blizzard and avalanche conditions. On February 26, the telegraph lines went down and communication with the outside was lost. On the last day of February, the weather turned to rain with thunder and lightning. Thunder shook the snow-laden Cascade Mountains alive with avalanches.

On March 1, sometime after midnight, Charles Andrews, a Great Northern employee, was walking toward the warmth of one of the Wellington’s bunkhouses when he heard a rumble. He turned toward the sound. In 1960, he described what he witnessed:

"White Death moving down the mountainside above the trains. Relentlessly it advanced, exploding, roaring, rumbling, grinding, snapping — a crescendo of sound that might have been the crashing of ten thousand freight trains. It descended to the ledge where the side tracks lay, picked up cars and equipment as though they were so many snow-draped toys, and swallowing them up, disappeared like a white, broad monster into the ravine below" (Roe, 88).

One of the 23 survivors interviewed three days after the disaster stated:

"There was an electric storm raging at the time of the avalanche. Lighting flashes were vivid and a tearing wind was howling down the canyon. Suddenly there was a dull roar, and the sleeping men and women felt the passenger coaches lifted and borne along. When the coaches reached the steep declivity they were rolled nearly 1,000 feet and buried under 40 feet of snow" (Roe, 87).

A surviving train conductor sleeping in one of the mail train cars was thrown from the roof to the floor of the car several times as the train rolled down the slope before it disintegrated when the train slammed against a large tree.

Charles Andrews would not make it to the bunkhouse warmth for many hours. Along with other Wellington residents, Andrews rushed to the crushed trains that lay 150 feet below the railroad tracks. During the next few hours they dug out 23 survivors, many with injuries.

In the days that followed, news reports of the tragedy that reached the rest of the country were largely inaccurate. On March 1 there were reports of 30 feared dead. On March 2 there were "15 bodies ... recovered ... [and] 69 persons missing. One hundred and fifty men, mostly volunteers, are working to uncover the dead." On March 3 a headline stated, "VICTIMS NOW REACH 118."

The injured were sent to Wenatchee. The bodies of the dead were transported on toboggans down the west side of the Cascades to trains that carried them to Everett and Seattle. Ninety-six people died in the avalanche, including 35 passengers, 58 railroad employees sleeping on the trains, and three railroad employees sleeping in cabins enveloped by the avalanche.

After

The immediate cause of the avalanche was the rain and thunder. But, conditions had been set by the clear cutting of timber and by forest fires caused by steam locomotive sparks, which opened up the slopes above the tracks and created an ideal environment for slides to occur.

It took the Great Northern three weeks to repair the tracks before trains started running again over Stevens Pass. Because the name Wellington became associated with the disaster, the little town was renamed Tye. By 1913, to protect the trains from snow slides, the Great Northern had constructed snow-sheds over the nine miles of tracks between Scenic and Tye.

Disaster struck again on January 22, 1916, when eight passengers were killed when an avalanche swept down Windy Mountain and struck a westbound Great Northern passenger train, shoving two rail cars over an 80-foot embankment. The disaster occurred near Corea station, seven rail miles west of Tye.

In 1929, a new tunnel was built, making the old grade obsolete. This 1929 tunnel is still today (2003) used by the Burlington Northern Sante Fe Railroad.

The old grade is now the Iron Goat Trail, a hiking trail through the forest and past various examples of railroad archeology. The name Iron Goat was taken from the Great Northern Railway corporate symbol -- a mountain goat standing on a rock. "Iron goat" was applied to Great Northern locomotives working the mountainous rail lines in the Rockies and Cascade.