On April 15, 1954, Bellingham, Seattle and other Washington communities are in the grip of a strange phenomenon -- tiny holes, pits, and dings have seemingly appeared in the windshields of cars at an unprecedented rate. Initially thought to be the work of vandals, the pitting rate grows so quickly that panicked residents soon suspect everything from cosmic rays to sand-flea eggs to fallout from H-bomb tests. By the next day, pleas are sent to government officials asking for help in solving what would become known as the Seattle Windshield Pitting Epidemic.

It Begins in Bellingham

The tiny windshield holes were first noticed in the northwestern Washington community of Bellingham in late March 1954. The small size of the pits led Bellingham police officers to believe that the damage was the work of vandals using buckshot or BBs. Within a week, a few residents in Sedro Woolley and Mount Vernon, 25 miles south of Bellingham, also began reporting damage to their windshields. By the second week of April the “vandals” attacked farther south, in the town of Anacortes on Fidalgo Island.

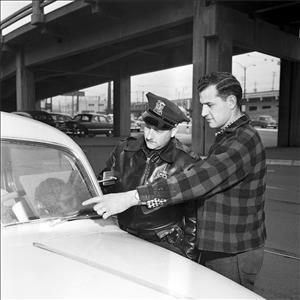

The Anacortes outbreak began early in the morning on April 13, 1954, when car owners noticed the heretofore-unseen pits in their windshields. Losing no time, all available law enforcement officers in the area sped to town in the hope of apprehending the culprits. Roadblocks were set up south of town at Deception Pass Bridge, and all cars leaving and entering the city were given a detailed once-over, as were their drivers and passengers.

To no avail. Farther south, cars at the Whidbey Island Naval Air Station at Oak Harbor were discovered to have the same mysterious dings. Nearly 75 marines made an intensive five-hour search of the station. They came up empty. By the end of the day, more than 2,000 cars from Bellingham to Oak Harbor were reported as having been damaged. Two things became abundantly clear: This could not be the work of roving hooligans; and whatever was causing windshield pits and dings was rapidly approaching Seattle.

Seattle Under Siege

News of the windshield ding-phenomenon reached Seattle ahead of the menace. On the morning of April 14, 1954, Seattle newspaper subscribers read frontpage reports of the events that had transpired to the north. The afternoon papers carried similar stories. At 6 p.m. a report came in to Seattle police that three cars had been damaged in a lot at 6th Avenue and John Street. At 9 p.m., a motorist reported that his windshield had been hit at N 82nd Street and Greenwood Avenue. Then the floodgates opened.

Motorists began stopping police cars on the street to report windshield damage. Parking lots and auto sales lots north of downtown were hit, as well as parked cars as far west as Ballard. Even police cars parked in front of precinct stations suffered damage. Extra clerks were brought into the stations to answer the flurry of calls from angry and perplexed car owners. By the next morning, windshield pitting had reached epidemic levels.

Glass Menagerie

The sheer number of damaged windshields ruled out hoodlums, and experts were at a loss as to the cause of these strange pits and holes appearing out of nowhere. On Whidbey Island, Sheriff Tom Clark postulated that radioactivity released by recent H-bomb tests in the South Pacific was peppering windshields. Geiger counters were run over windshield glass, and also over persons who had touched the pit marks, but all were free of radioactivity. Still, the sheriff held firm that “no human agency” could have created the scars left on the glass.

Other theories abounded:

- Some thought that the Navy’s new million-watt radio transmitter at Jim Creek near Arlington was converting electronic oscillations to physical oscillations in the glass. Navy Commander George Warren, in charge of Jim Creek, called this theory “completely absurd.” He pointed out that a windshield would have to be several miles wide to match the frequency of the transmitter, and besides, no pitting incidents were found at Jim Creek, home of the transmitter.

- Cosmic rays bombarding the earth from the sun were considered as a cause, but since so little was known about cosmic rays, this theory couldn’t be readily proved or refuted.

- A mysterious atmospheric event was theorized, but supporters of this theory couldn’t explain what atmospheric condition this could possibly be.

- Since a few people amazingly reported seeing the glass bubble right before their eyes, some postulated that sand-flea eggs had somehow been laid in the glass and were now hatching. How this could occur and why they would all hatch at once was not clear.

- Others suggested supersonic sound waves, non-radioactive coral debris from nuclear bomb tests, or a shift in the earth’s magnetic field.

- Other folks simply boggled and blamed the entire event on gremlins.

Then there were the skeptics. Dr. D. M. Ritter, University of Washington chemist, was assigned to work with authorities on the case. After inspecting windshields and residue found on some of the cars, he commented, “Tommyrot! There isn’t anything I know of that could be causing any unusual breaks in windshields. These people must be dreaming.” Dr. Ritter was closer to the truth than anyone.

Save Us, Ike!

By April 15, 1954, police were swamped with calls. Close to 3,000 windshields had been reported as being pitted, and no one knew what to do. Looking for outside help to solve the enigma, Seattle Mayor Allan Pomeroy (ca. 1907-1966) wired Governor Arthur Langlie at the state capitol in Olympia, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower at Washington D.C.:

What appeared to be a localized outbreak of vandalism in damaged auto windshields and windows in the northern part of Washington State has now spread throughout the Puget Sound area. Chemical analysis of mysterious powder adhering to damaged windshields and windows indicates the material may simply be spread by wind and not a police matter at all. Urge appropriate federal (and state) agencies be instructed to cooperate with local authorities on emergency basis.

Governor Langlie contacted the University of Washington and requested that a committee of scientists be formed to investigate the phenomenon. The experts (from the environmental research laboratory, the applied physics laboratory, and the chemistry, physics, and meteorology departments) did a quick survey of 84 cars on the campus. They found the damage to be “overly emphasized,” and most likely “the result of normal driving conditions in which small objects strike the windshields of cars.” The fact that most cars were pitted in the front and not the back lent credence to their theory.

King County Sheriff Harlan S. Callahan disagreed. His deputies examined more than 15,000 cars throughout the county, and found damage to more than 3,000 of them. The Sheriff and his deputies believed that this level of damage could not be explained by ordinary road use. The law enforcement officers also found odd little pellets near some of the cars. Using crack scientific methods, they found that the pellets reacted “violently” when a lead pencil was placed next to them, but not when a ballpoint pen was so placed. Nobody knew what this meant, though.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Nevertheless, conventional wisdom lay with the scientists. Further investigation by the City of Seattle Police Department showed that most dings pitted older car windshields. In cases where auto lots were involved, brand new cars were unpitted, whereas used older cars showed signs of pitting. Police found rare instances of “copycat” vandalism, but most of the cases had a simple explanation: The pits had been there all along, but no one had noticed them until now.

The same reasoning applied to particulate matter found on windshield glass and near cars. It was found to be coal dust, tiny particles produced by the incomplete combustion of bituminous coal. These particles had drifted in Seattle air for years, but no one had looked closely at them before. Although the coal dust particles had nothing to do with the pitting, the populace at large finally noticed them, just as they noticed the window dings, for the very first time.

Sergeant Max Allison of the Seattle police crime laboratory declared that all of the damage reports were composed of “5 per cent hoodlum-ism, and 95 per cent public hysteria.” Puget Sound residents had unwittingly become participants in a textbook example of collective delusion. By April 17, 1954, pitting incidents abruptly ceased.

One for the Books

The Seattle Windshield Pitting Epidemic of 1954 did indeed become a textbook example of collective delusion, sometimes mistakenly referred to as “mass hysteria.” To this day, sociologists and psychologists refer to the incident in their courses and writings alongside other similar events, such as Orson Welles’ Martian invasion panic of 1938, and supposed sightings of the “Jersey Devil” on the East Coast in 1909.

The Seattle pitting incident contains many key factors that play a part in collective delusion. These include ambiguity, the spread of rumors and false but plausible beliefs, mass media influence, recent geo-political events, and the reinforcement of false beliefs by authority figures (in this case, the police, military, and political figures).

This combination of factors, added to the simple fact that for the first time people actually looked "at" their windshields instead of "through" them, caused the hubbub. No vandals. No atomic fallout. No sand-fleas. No cosmic rays. No electronic oscillations. Just a bunch of window dings that were there from the start.

You probably have them on your car right now. Please don’t alert the media or your local police.