The Northwest's system of roads and highways did not evolve easily. At the turn of the twentieth century, few roads were paved or even improved and county projects were not coordinated with one another. A combination of capitalists and progressives under the leadership of Seattle businessman Sam Hill (1857-1931) organized the Washington State Good Roads Association, which lobbied the Washington and Oregon legislatures for the roads and highways to benefit all citizens. At the turn of the twenty-first century, the organization was still promoting good roads.

The movement for good roads started in the 1880s under the leadership of bicyclists from the League of American Wheelmen. Outside of cities, there was no coherent system of roads or highways. Good roads associations sprang up in several states. In Washington, property owners could either pay for roads through poll and property taxes, or work off the obligation with their own labor. What roads existed in Eastern Washington were largely the result of farmers pulling half-sawn logs behind a team to grade trails. County commissioners built roads, usually just graded tracks, within their counties with little attention paid to how the networks interconnected. In 1904, a survey showed that just 1 percent of the roads in the state was paved. Most of those were within cities.

Enter Sam Hill

The good roads movement in Washington began in earnest when Great Northern Railway executive Sam Hill (1857-1931) invited 100 men to Spokane to discuss improving the state's highways in 1899. Hill had shifted his business interests from Minneapolis to Seattle and headed the Seattle Gas and Electric Co. Hill's background in railroading (he was Empire Builder James J. Hill's son-in-law) taught him about the economics of transportation. Hill believed that if farmers could easily reach towns and rail connections, all would benefit. Hill and only 13 others showed up for the meeting, but they included visionaries such as Reginald H. Thomson (1851-1949), Seattle City Engineer. They formed the Washington State Good Roads Association and named Hill president. Hill declared, "Good roads are more than my hobby; they are my religion" and for the next 30 years he spent much of his energy and a million of his own dollars on the campaign.

The automobile was just coming on the scene and the need for improving highways was not shared by all. Farmers were suspicious of Hill's railroad background and of the heavy representation from cities and from Puget Sound in the association. County commissioners were jealous of their control of road budgets, which were funded by county property taxes. Hill and his colleagues lobbied the state legislature tirelessly. In 1905, the legislature created a state highway department headed by three commissioners, the 14th such agency in the nation. By 1907, the Good Roads Association could take credit for 10 laws passed at its urging and the state pledged all the costs of 12 state highways and half of approved county roads.

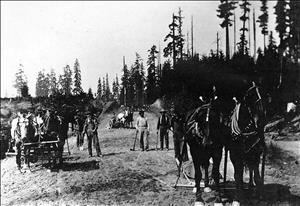

Hill personally pioneered many roads in his Locomobile and he stumped all over the Northwest generating support. He wrote articles, he gave speeches, and he sponsored excursions. He went to Washington, D.C., as early as 1900 looking for federal support for experiments in roadbuilding. In 1902 he proposed that the federal government subsidize state roads based on standard guidelines. The First American Congress of Road Builders was held in Seattle in 1909 at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in a specially constructed building that displayed roadbuilding technology. That same year, Hill used his ranch at Maryhill in Klickitat County to build 10 miles of demonstration roads, which showed off seven different surfacing techniques. These were the first paved roads in Washington.

Enter the Grange

By 1913, Washington farmers began to realize that the automobile was more than just a means of recreation for the urban elite. The car and truck became a viable alternative to a team and wagon and the state Grange rallied to the movement. That year, the legislature appropriated $2 million for roads and strengthened the state highway department. The watershed year was 1916, when the federal government stepped in with money for state highways. The first money paved 3.5 miles of the Pacific Coast Highway east of Olympia with one-course concrete.

Hill advocated convict labor to help build the state's highways and the program met with some success. Prisoners preferred road work to prison jute mills and the escape rate was fairly low. In 1911, Governor Marion E. Hay (1965-1933) pulled convicts off the road projects. The following year, Hill helped Hay's opponent, Ernest Lister (1870-1919) win the election on a platform of good roads.

In the 1910s, Hill's business interests took him to Klickitat County on the Columbia River Gorge and to Portland. He expanded his good roads campaign to Oregon. He paid for the Governor of Oregon and the entire Oregon Legislature to travel to Maryhill to see the 10 miles of demonstration roads he had built with his own funds.

Between 1906 and 1916, the number of motor vehicles in Washington increased almost 100 times, to 70,000. Between 1915 and 1920, the number of automobiles in the U.S. quintupled to 10 million. Overburdened railroads during World War I spurred some farmers into hauling their produce to market by truck, further demonstrating the value of better roads. The 1921 Federal Highway Act focused funding on an interstate system of highways and the 1920s saw a boom in highway construction.

Three highways of particular importance to the Washington Good Roads Association were the Pacific Coast Highway from Vancouver, B.C. to Tijuana, Mexico; the Inland Empire from Spokane to Ellensburg by way of Walla Walla and Pasco; and the Sunset Highway between Spokane and Seattle over Snoqualmie and Blewett passes.

Who Pays?

The first roads were funded by property taxes later supplemented by federal funds, special levies, and individual assessments. In 1919, the legislature imposed an excise tax of one cent per gallon of gasoline and the costs started to shift to the road user. In 1923, a one-mill property levy was repealed and roads were built and maintained with gasoline taxes and motor vehicle licensing fees. By that time, everyone with an automobile was part of the good roads movement.

During the Great Depression (1929-1939) road building served a social purpose by providing economic relief. Emphasis shifted from a state system to addressing local needs again. The highway fund was used for more than just highways. In 1944, with the support of the Good Roads Association, Washington voters passed the 18th Amendment to the state constitution prohibiting use of the gasoline tax for anything but highways. The end of World War II saw another highway boom as Americans bought more cars and 75 percent of the nation's freight was being hauled by truck. At mid-century there was a nationwide crisis in highway congestion and the Good Roads Association joined in a demand to "get our people out of the mess" (Dorpat, 91).

The need for highways shifted from serving recreational drivers and farmers to moving residents between the cities and their new suburban homes.

The 1950s saw a resurgence of opposition to more highways. The construction of high-speed, limited-access freeways devoured property and neighborhoods. Citizens reacted. Activists blocked a system of freeways in Seattle in the 1960s and litigation delayed an expansion of Interstate-90 through the Mount Baker neighborhood and Mercer Island.

The Washington State Good Roads Association evolved into the Washington State Good Roads and Transportation Association, still active after 103 years.