Northwest artist Clayton James has worked with many types of media: he has painted landscapes, made furniture, and sculpted in clay, wood, and concrete. Not originally from the Northwest, he was attending Rhode Island School of Design when World War II broke out, and he declared himself a conscientious objector. After assignment to other conscientious objector camps in the East, he was transferred to a camp for artists in Waldport, Oregon. There he met and befriended Morris Graves, who was invited in for an artist's residency. He has lived in the Northwest ever since, creating art that reflects the influences of this area. This biography of Clayton James is reprinted from Deloris Tarzan Ament's Iridescent Light: The Emergence of Northwest Art (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002).

From Midwest to Northwest

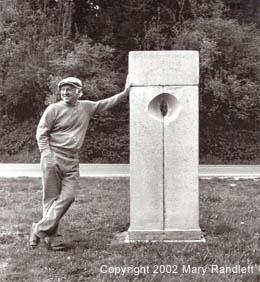

Anyone meeting Clayton James for the first time must be impressed with the clear, bright blue of his eyes. His most prominent feature, they look out at the world with the fresh clarity of a child. That freshness of vision, coupled with a stubbornness about not yielding to the patterns of a working life usually expected by society, allowed James to produce a body of work as notable for its simplicity as for its originality.

Clayton James had a Midwestern upbringing, but fit into the Northwest aesthetic as naturally as he drew breath. Growing up in Belding, Michigan, he knew he wanted to be an artist, not for the possibilities of name or fame, but as a way of life. He prized creative freedom over economic security.

It was a heritage from his parents. His father, Albert (usually called Jim), was the youngest of 11 children, and loved to grow vegetables and flowers. In his latter years, he customarily spent Sunday afternoons calling on the sick and elderly. Clayton's mother, Neva Ann Sturgeon, wrote poetry. Before Clayton was born, Neva and her husband, their daughter, and two older sons moved from Chicago to what they envisioned as a "dream farm" in Michigan. Clayton was born there in February 1918. The "dream farm" proved to be a sandlot. Economics soon forced the family to move to nearby Belding. For the rest of his working life, Clayton's father worked as head dyer for a silk thread mill, matching colors. Clayton was a teenager when the mill moved to Putnam, Connecticut, and the James family moved with it.

The family tree held no artists, but did have an abundance of musical talent. (Albert's acute color sense was not inherited by his sons; all of them were color blind.) Clayton's brother Walter was a tenor who majored in sacred music, and taught in the music department at Florida State University.

After Clayton graduated from high school, the Rhode Island School of Design awarded him a scholarship that covered the $75 tuition. He worked in the cafeteria to meet living expenses. His summers were spent painting landscapes in Provincetown, Massachusetts. One fellow artist and RISD student, Barbara Straker, would later become his wife.

Conscientious Objecting

When World War II broke out in 1942, James declared himself a conscientious objector. He was assigned to a Quaker camp in Petersham, Massachusetts, cleaning up brush and fallen trees left in the wake of a 1938 hurricane, and digging water holes to fight forest fires. When the work was done and that camp closed, he was transferred to a similar camp in Big Flats, New York, and later to a camp for artist conscientious objectors in Waldport, Oregon. He hitchhiked from the train out to the camp, where he recalls being wowed by knee-high skunk cabbage (James Interview). Barbara followed. She and James were married in Toledo, Oregon, in June 1944, on the day before D-Day.

The government-run work project at the Waldport camp was reforestation of the denuded coastal mountain range. Poet William Everson was in charge of an after-hours fine arts program that gave plays and concerts and produced books of poetry. The purpose of the program was as much to boost morale as to stimulate creativity.

Meeting Morris Graves

Artists were invited to the camp for brief guest residencies. James had seen Morris Graves's paintings in New York in an exhibition titled Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States and was sufficiently impressed to visit the Marian Willard Gallery, which represented Graves. There he learned of Graves's pacifist leanings, and his struggles with the military. Knowing Graves lived in Washington state, James urged Everson to invite him to the camp as a guest artist.

Barbara James recalls that Graves's friend Dorothy Schumacher, who was with him when the invitation arrived, said Graves was so excited he almost packed up and left immediately. He was curious what conscientious objectors would be like. Although the war was still raging, Graves had won a discharge from the army by a combination of legal action and noncompliance; a model of civil disobedience in the spirit of Thoreau and Gandhi (Barbara James to Deloris Tarzan Ament, January 2000).

Graves responded to James's invitation, but as James recalls, "He'd been in camp for a week before we knew it. He'd found an opening in the woods and built a lean-to, and was painting." One day when Clayton and Barbara were walking along the highway, a Model A Ford rattled to a stop. Graves, who was traveling with his two small dogs, stopped the car and walked back to introduce himself.

Barbara James recalls, "As a guest of the camp, it had been assumed that Graves would stay in the guest barracks and take his meals in the mess hall." But he had had his fill of military life. Instead, he found a site just off the beach in a nest of pine trees near a creek. He bought a few bundles of cedar shakes from a local shake mill, "roofed over a space, built a bunk, attached a couple of walls, tossed down a few Chinese mats and was ready to meet the camp. In future years, Clayton often built forest lean-tos inspired by this dwelling. The coast was patrolled daily by a Navy blimp, so it was not long before Morris's presence was discovered and investigated by federal authorities," Barbara James recounts.(James to Ament, January 2000).

Graves stayed for nearly two months, meeting with the conscientious objectors, whose numbers included artists, Mennonites, Jehovah's Witnesses, and the Brethren. Graves painted while he was there, and mounted a small exhibition before he left.

In the spring of 1945, Graves invited the Jameses to spend Clayton's furlough at The Rock, overlooking Lake Campbell. They accepted. With morale deteriorating in the camp, Clayton had decided he would not return. He and Barbara hitchhiked up the coast, hitching rides on logging trucks. Clayton built a lean-to at the edge of the lake, where they stayed for most of the summer. Graves paid them $7 a week to clear brush, as a means of survival.

When they returned to camp at the end of July, James was picked up by the F.B.I. for having stayed absent beyond his leave. He was in jail overnight in Portland awaiting trial. Because Barbara was there in the courtroom, the judge let him off with a suspended sentence. Perhaps it was also because the end of the war was in sight, and nearly everyone was in the mood for leniency.

Basic and Direct

The Jameses moved to Washington state, settling for a while on Hood Canal, then moving to Seattle. There, from 1948 to 1950, Clayton, wearing a bushy beard two decades ahead of hippie fashion, made a living weeding the Arboretum -- the only 8-to-5 job he ever held. With the pay, he bought his first car, a Model A Ford, in which he and Barbara drove every weekend to the Olympic Mountains, or to the coast. His career, like that of many artists, was circumscribed by economics. Torn between the need to make a living and the emotional need to devote himself to making art, he made the clear choice that must be made by any serious artist to save his mental and emotional energies for the act of creation.

Barbara remembers:

"His approach to the world around him was basic and direct. He first had to learn how to split shakes. Then to make benches and three-legged stools. Then lean-to dwellings on the coast and in the forest. A tangled knot of windswept pines would do. A bed of beach grass, nightly soaked with fog. He made drawings and paintings, often abandoning them in the woods along with his shoes. He lived off the land, his summer diet consisting largely of mushrooms, oysters and salmon. He illustrated books of poetry for friends, wove rugs out of burlap bags, and made leather sandals. Richard Gilkey bought the first pair, and complained that the thongs hurt his toes" (James to Ament, January 2000).

The Jameses bought 22 acres in Woodway Park, near Edmonds, for $1,800, adjoining land on which Graves had built a house. They built with lumber Graves had salvaged from an old chicken coop.

Working with a Master Woodworker

In 1950, when Clayton was 32, on Graves's recommendation, he wrote to apply for an apprenticeship with master woodworker and furniture maker George Nakashima in New Hope, Pennsylvania. Nakashima accepted him as an apprentice, and James subsequently spent a year and a half working with him.

Nakashima was born in Spokane, Washington, to a family with an aristocratic history. His mother had served in the court of the Meiji emperor. Nakashima earned degrees in architecture from the University of Washington and M.I.T. His first major architectural assignment was in Pondicherry, India, where he designed Golconda, the primary disciples' residence at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. Sri Aurobindo gave him the Sanskrit name Sundaranananda, meaning "one who delights in beauty."

Nakashima had been living in Seattle with his wife and baby at the time the United States declared war on Japan. He was interned at Minidoka, Idaho, until 1943, when he was permitted to resettle in New Hope, Pennsylvania, where he opened his famous workshop. Nakashima's work is famous for its elegant simplicity and its fidelity to materials -- elements that came to be hallmarks of James's future sculpture as well.

The Jameses traded in their Model A Ford for a Jeep station wagon in Pennsylvania, in part because they had bought the first mattress of their married life in New Hope, and Barbara wasn't going to leave it behind. At the end of Clayton's apprenticeship, they loaded the station wagon with the mattress and Nakashima furniture, and headed back to Seattle.

Totems in Wood and Clay

James worked briefly at cabinet shops, and sporadically in a cannery and as a field hand, all while trying to paint. Clayton and Barbara began to spend their summers in the small fishing village of La Conner in 1953, at about the time Guy Anderson moved there. Barbara was still painting, but Clayton was finding the going heavy. On Cape Cod, the thrust of his work had been landscape painting. But with the great surge of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s came the curious conviction that any artist who wished to be taken seriously must adopt the then-new style of bravado abstraction. "I didn't have a theme, so I couldn't paint," James said simply. "I tried to be an abstract expressionist, but it just wasn't working" (Interview).

In a solution no less brilliant for being intuitive, he switched media. University of Washington art professor Ruth Pennington held a summer school in which Jim and Nan McKinnell, potters from the Archie Bray Foundation in Montana, came to La Conner to teach. Studying with them, James discovered he had a natural deftness with clay.

But, not until a decade and a half later did he begin to use clay as his primary material for sculpture. When he did, the forms were so simple and natural that they might have mushroomed from the duff under fir trees in the deep woods.

A trip to Europe in 1966, during which he visited Europe's great museums, caused a deep dissatisfaction with his own work. He began to work directly in concrete and wood; to think in terms of sculptural form. Shapes from his paintings began to emerge in the round.

He exhibited his first concrete and wood combination sculpture in the Henry Art Gallery's Summer Salon in 1967, followed by his first solo show, at the Northwest Craft Center in 1970. Art critic John Voorhees likened the brightly painted, vaguely anthropomorphic forms to contemporary totems (Voorhees).

Cultural Flow From the Ancients

Concrete and wood are weighty materials. In 1973, back trouble sent James in search of something lighter. Clay potentially filled that bill, although the coil pots he hand-built in pink earthenware or buff stoneware often tipped the scales at 50 pounds or more. Hand-building permitted him freedom from the symmetry that necessarily accompanies wheel-thrown pottery. He produced smooth, irregular clay bodies, bellied on the underside, with a soft ridge along the top leading to an out-of-round opening sliced into the body of the pot.

His unglazed pots were pure form, with the clean simplicity of Brancusi sculptures. White gesso rubbed directly into the clay body gave some of the pieces a glossy, pristine finish. Others were stained with dark, impregnating smoke. The expressive subtleties of abstract organic form were the finest work of his career. The smooth ceramics were in tune with minimalist art current in the mid-1970s. Yet they were also, as James said, "a continuum of the cultural flow from the ancients" (Interview).

The shapes suggested eggs and butterfly chrysalises. Old-time Northwest observers saw in them direct quotations of the wind-sculpted, water-worn rocks of Washington beaches.

Earth's Dust

In 1976 to 1977, a three-month trip to the Southwest profoundly influenced James's art. He admired the direct, accessible forms of Southwest Native American art. He began to think of ceramics as "wads of earth's dust concentrated and shaped" (Tarzan). To James, they were a part of a continuum in time.

His new body of work reflected the Southwest influence. Deep, dusky pink, several feet high and at least a foot wide. James continued a line of organic sculptural abstraction that equated hillocks and the declivities of valleys with the swells and curves of the human body. There was a voluptuous sensibility to the ovoid shapes with the texture of river stones that tapered to slightly offset necks. They recalled Native American basketry and ceramics, innocent of ceremonial patterning.

In 1978, critic Richard Campbell wrote, "More than objects of art, James' ceramic pieces seem to represent a certain spirituality of place. There is something almost religious in their appeal, their approach, their manner. Not the religion of Renaissance refinement, but something more fundamental" (Campbell).

Breaking Out of Clay

Despite the critical and commercial success of the pottery, it left James dissatisfied. Much of it was drone labor, working with 65 pounds of clay rolled into coils, built into pots that had to dry in stages and often broke during firing, to his immense frustration.

For a short while, he worked in bronze -- a medium he seems never to have enjoyed. "I wasn't free. What a job to have to do the foundry work. I had a terrible time with technique" (Interview).

He quit making sculpture after his 1991 show at the Woodside/Braseth Gallery. He had made all the forms for that show, leaving the firing until shortly before the deadline for the exhibition. When he fired them, they all split at the bottom. He patched them and put them in the show, but the work had begun to feel oppressively claustrophobic.

Retreating From Visibility

He despised what he saw as the stuffiness and commercialism of the Seattle gallery scene. "I have never really worked for shows. It's too much stress. When I did, my work just got tighter and tighter," he explained. "Showing in Seattle wrecks everything I think I'm doing" (Interview). He particularly dreaded the social and emotional pressure of gallery openings.

By this time, with the emphasis on abstraction gone, he returned once more to painting landscapes. After 30 years he had experienced as "being cooped up in the studio for 10 to 12 hours a day," he felt liberated to be outdoors painting. He especially enjoyed painting outings with Paul Havas, when they spent a week or more east of the mountains. "It's fine as long as it isn't serious," he said, meaning so long as his painting wasn't being done in preparation for an exhibition. "When it's serious, the paintings have to work. Lot of pressure. It has to take all the talent you've got" (Interview).

In retreating from Seattle exhibitions, he made himself less visible to the Northwest art scene. His landscape paintings did not create the same critical stir accorded his sculptures. Barbara became more publicly visible than Clayton when she began to do volunteer curatorial work at the fledgling Museum of Northwest Art in 1991, shortly after Susan Parke became the museum's director. She was hired as curator in 1995.