On October 7, 1904, the battleship Nebraska is launched from the Moran Brothers shipyard in Seattle. Tens of thousands attend the event, some of whom contributed money to help Moran Brothers win the federal contract for its construction. The Nebraska is the only battleship ever built in Washington.

Built with Public Support

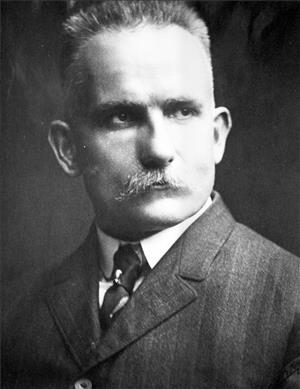

In 1899, the construction of three coastline battleships was authorized by an act of Congress. Robert Moran (1857-1943), president of the Moran Brothers Company, submitted the lowest bid to build one of them, but it was still $300,000 more than the navy wanted to pay. Knowing how important this contract was to Seattle -- a city still reeling from massive growth following the 1897 Klondike Gold Rush -- Moran asked the Seattle Chamber of Commerce for help.

Moran offered to pay two thirds of the overage if the Chamber could convince local businesses and individuals to raise the other $100,000. In a matter of days, the money was raised to build the first large ship in the Pacific Northwest. The vessel was originally going to be named the Pennsylvania, but congressional members from that state balked, saying that their state's namesake should be built in Philadelphia. The name Nebraska was chosen instead.

The contract was formally awarded on March 7, 1901, but because of labor strikes and delays in the delivery of materials, work did not begin until the following year. On July 4, 1902, more than 7,000 people, including a delegation from Nebraska headed by Governor Ezra P. Savage (1842-1920), visited the Moran shipyard to witness the laying of the keel -- the first step in building the vessel. Governor Savage and Washington Governor Henry McBride (1856-1937) drove the first rivets, and each received a check from Robert Moran for three cents -- the wage scale for such work at the time.

A Massive Undertaking

Construction of the ship required major renovations at the shipyard, located at the foot of South Charles Street south of Seattle's Pioneer Square. Since the Moran Brothers Company had never built a ship of this size before, many heavy shop tools and a large amount of equipment were purchased. The ship shed, 100 feet wide and more than 600 feet long, was built with easy access to nearby rail lines to facilitate the delivery of materials. A system of electric traveling cranes was installed over the building slip with connections to all of the shops.

More than 1,000 workers helped build the Nebraska, which outweighed any warship previously launched in the United States by more than 1,000 tons. The vessel was 441 feet long with a beam of 76 feet. Her planned top speed was 19 knots.

The day before the launch, the Moran Brothers Company shut down work at the shipyard and opened it up to the public so everyone could see the massive battleship up close. All day long, large crowds thronged to see the vessel. Groups of schoolchildren visited in the afternoon, and many of them were just as interested in seeing what kind of work went on in the shops and sheds throughout the yard. People came to see the Nebraska well into the night, when the ship was brightly illuminated. A giant "NEBRASKA" sign pointed the way, with letters more than 12 feet high made out of electric bulbs.

Gathering Together

On October 7, most businesses in the city closed up shop so employees could go to the launch. Seattle schools started an hour earlier that day and let out just after noon, giving children enough time to make it to the waterfront to see the Nebraska go down the ways. Seattle Mayor Richard Ballinger (1858-1922) wasn't able to declare a general holiday but did allow various city departments to grant employees a few hours of vacation to witness the event.

The battleship was scheduled to launch at 2:13 p.m., but people started showing up in the morning to get the best view possible. Many of them packed picnic lunches and camped out on lumber piles or any place with a good vantage point. By noon, more than 40,000 people had crammed onto and into almost every open spot near the launch site. An estimated 15,000 people watched from boats, and more than 2,000 people even filled the Centennial Mill wharves, which were a considerable distance to the south.

Those wishing to watch the launch from the water had to follow strict guidelines set up by the navy. Two imaginary lines were established on either side of the Nebraska, marked 620 feet out on the water by two stake boats. No vessels were allowed within those boundaries except for the revenue cutter Grant and the monitor Wyoming -- both naval vessels -- and three press boats -- one each for The Seattle Times, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, and Seattle Star.

There was some concern that when the Nebraska hit the water, it would create a large wave. All of the viewing boats outside the boundaries were requested to point their bows in the direction of the battleship so as not to be swamped if the wave was too large.

Back on shore, the mood was festive. Every now and then, some wag would exclaim, "Look, there she goes," and those nearby would quickly turn their heads before realizing they'd been japed. Almost everyone was in good spirits, except for one old curmudgeon who sat on a pier just to the right of the Nebraska. Dubbed "Sunny Jim" by one of the spectators, the sour fellow offered up a litany of worries and complaints, grousing that anyone who showed up to watch was a fool and that the boat was going to cause a tidal wave that would wash everyone off the pier into the water.

Speakers and Guests

Inside the construction shed, the Nebraska was festooned from bow to stern with flags, ribbons, and red, white, and blue bunting. A platform was built near the bow for the christening ceremonies and ornamented with flags and evergreens. On it stood Mayor Ballinger, Nebraska Governor John H. Mickey (1845-1910), and his daughter Mary (1881-?), who was given the honor of christening the ship. Also in attendance was Acting Governor and Secretary of State Samuel Nichols (1830-1913), who was filling in for Governor McBride while the governor represented Washington at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Joining the group were delegations from every military post on the West Coast and a host of other dignitaries.

The ceremony began at 12:30 p.m. with a selection of marching bands and included a performance of the new "Nebraska March," specially composed by Professor Sol Asher (1864-1972). At 1 p.m. the speakers took to the stage, beginning with Mayor Ballinger, who introduced Acting Governor Nichols. When Governor Mickey spoke, he mentioned that people in his state knew very little about ships, but they did know about prairie schooners, which had crossed through Nebraska on their way to Washington.

One highlight of the event came when President John Schram (1856-1929) of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce presented Robert Moran with a $100,000 check -- the money raised by Seattle boosters to build the ship. Just before 2 p.m., Senator William Humphrey (1862-1934) stepped up to the podium to deliver the last speech before the invocation by Reverend Mark Matthews (1867-1940). Humphrey was halfway through his talk when a loud cracking noise came from behind.

Down the Ways

Throughout the presentation, workers had been slowly removing the timbers that kept the Nebraska in place until its launch, scheduled for 2:13 p.m. when the tide would be at its highest. Just as the saws started cutting into the last two timbers, the weight of the vessel proved to be too much, and the beams began to shatter during Senator Humphrey's speech. Worried that the ship would stall on the greased runways if the task was delayed, a go-ahead was given to launch the vessel 10 minutes early.

The battleship began to shudder, then move. Young Mary Mickey, acting fast, grabbed the champagne bottle -- which was hanging from a rope -- and pitched it at the vessel, exclaiming, "I christen thee, Nebraska!" Just in time, the bottle shattered against the bow as the great ship slid down the ways.

Although rushed, the launch went more smoothly than expected. Instead of creating a huge wave when it hit the water, the ship barely made a ripple as it slid into Puget Sound. A thunderous roar of cheers and applause went out from the thousands who had gathered to watch. A cacophony of bells, blasts, and gongs were sounded from every boat within sight of the launch. On shore, the marching bands played "Auld Lang Syne" as the ship gracefully floated out into Elliott Bay.

Mementos

No sooner had the boat become stationary than there was a mad rush inside the construction shed of people wishing to grab some souvenir from the launch, be it wood splinters, steel rivets, copper shavings, or anything else that was loose and easy to grab. Shards from the champagne bottle were hunted down, although one mischievous young boy found some beer bottles and, after surreptitiously shattering them, offered them up to souvenir hunters as pieces of the real christening bottle.

One man climbed up on the grandstand and addressed the crowd. "Ladies and gentlemen," he said, "did you ever hear that magnificent poem of Longfellow's 'The Launching of the Ship?'" (Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 8, 1904). He proceeded to recite the poem, hoping to provide some culture for the masses, but they would have none of it. He had only gotten a few lines in when someone in the crowd yelled out, "Soak him!" Someone else heaved a chunk of grease which smacked the orator right on the side of the head.

That night a reception was held at the Washington Hotel for the visitors from Nebraska. Mary Mickey proudly showed off the gold watch she had received from the shipyard workers, inscribed with a message from Robert Moran. She had also managed to save the ribbons from the christening bottle, which she kept as a memento.

A Ship's Career

The next day, the Nebraska visitors got a tour of the ship, which was now tied up at the dock. Naval officials told them of the massive work now needed to fit out the ship with turrets and armaments.

It took two years to complete the work, and in July 1906 the Nebraska underwent sea trials near Vashon Island. The vessel reached speeds of 19.5 knots, slightly more than the navy requirement. On July 1, 1907, the vessel was officially handed over to the navy at the Bremerton Naval Yard. The completed cost of the ship was $6,832,796.96 -- an enormous amount of money for its time.

The Nebraska became part of President Theodore Roosevelt's Great White Fleet and toured the globe in a show of American naval power. During World War I, the Nebraska saw little action and was used mainly for troop transport. The ship was decommissioned in 1923 and sold for scrap.