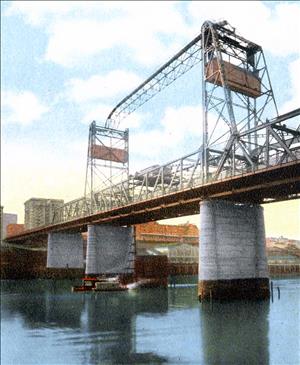

On February 15, 1913, Tacoma's Eleventh Street Bridge spanning the City Waterway opens. A crowd of some 10,000 Tacomans celebrates the opening of the steel-truss, vertical lift bridge with speeches, a champagne christening, and a shower of red carnations flung from the upper railing. From an engineering point of view, the Eleventh Street Bridge (in 1997 renamed the Murray Morgan Bridge) is remarkable in three ways. It is built on a grade, its deck is unusually high for a vertical lift bridge, and it features an overhead span for carrying a waterpipe. The bridge is an essential infrastructural link between the commercial downtown Tacoma and the industrial tideflats.

Replacing Inefficiency and Exasperation

The Eleventh Street Bridge replaced a swing-span bridge completed in 1894 that spanned a narrow arm of Commencement Bay. (Between 1902 and 1905, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers extended this arm of the bay to create the City Waterway, later renamed Thea Foss Waterway.) The original swing span bridge inspired indignation and outrage among tugboat and steamship owners from the time it opened until it was replaced in 1913. The bridge was built too low, was unusually inefficient to open, and caused numerous episodes of unmitigated waiting.

The Kansas City, Missouri, firm of Waddell and Harrington, the country's leading firm in the design of vertical lift bridges, was chosen to design the new bridge. The firm decided on the vertical lift design mainly for its potential height and to have a way to get a waterpipe across the waterway to the tideflats. The waterpipe would be run across the top chord of the truss, above the traffic.

During construction, the swing span of the old bridge was swung around to meet a temporary road built on trestles and thus road and water traffic continued unimpeded throughout the two-plus years of construction. This ingenious arrangement "elicited the wonder of thousands of beholders" (quoted in Jonathan Clarke, "City Waterway Bridge").

Design and Structure

The bridge (which was modified in the 1950s) consisted of two approach spans, two fixed truss spans (each with a tower), and the central vertical lift span. The truss is in the Pratt design and the struts are riveted together, making them stronger. The fixed truss spans are set on four reinforced concrete piers, which in turn are set on piles driven into the ground to a depth of 115 feet. The central piers are each set on 200 piles, the outer piers on 150 piles.

The lift span is hung from the towers with steel rope. It is operated from a house built directly on the span. The lift works by electric motors, pulleys, and concrete counterweights inside the towers (it can also be operated manually in case the motors fail). The original roadway was made of creosoted wooden paving blocks supplied by the St. Paul and Tacoma Lumber Company. (It was replaced with a lightweight concrete roadway after heavy use and wear during World War II.) The original roadway had pedestrian walkways, a roadway for highway traffic, and tracks for the street railway owned by the city.

Carnations and Champagne

Tacoma was ecstatic at the opening of its new bridge. "We of Tacoma should be proud of this grand structure," said Mayor W. W. Seymour at the opening ceremonies. T. H. Martin, Secretary of the Commercial Club and Chamber of Commerce added, "Nothing has been done for years that means as much to the industrial development of Tacoma as the building of this highway to the tidelands" (quoted in Jonathan Clarke, "City Waterway Bridge"). Carnations were thrown from the upper railing, and the president of the contracting firm distributed free cigars to the crowd. The lift span was lifted to its greatest height, then lowered and dashed with a bottle of champagne. The crowd cheered.