On March 28, 1934, six people are massacred in a beach house on Erland’s Point, six miles northwest of Bremerton, in Kitsap County. Three days later, neighbors are alerted to the murder scene by barking dogs. Fueled by excessive and sensational press coverage, the murder investigation turns into a circus. After a week, the investigation stalls and the killer’s trail grows cold. In October 1935, 18 months after the sensational crime, Leo Roderick Bernard Hall, age 33, an ex-fighter and dry-dock worker is arrested for the mass murder. In another news-frenzied event, Leo Hall is hanged at the state penitentiary in Walla Walla on September 11, 1936.

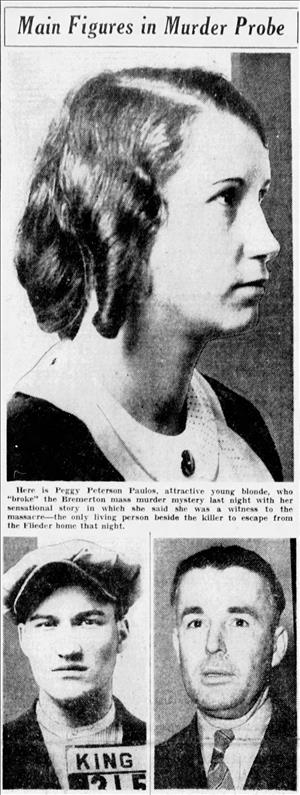

His accuser was Peggy Peterson Paulos, age 27, a local barmaid and waitress, who told police she was Hall’s reluctant accomplice in a bungled robbery at Erland’s Point. When the killing began, Paulos ran for her life. Both Hall and Paulos were charged with the murders in Kitsap County and went to trial in December 1935. The jury convicted Hall of first-degree murder, sentencing him to death; Paulos was acquitted and set free.

Discovering the Crime

On Saturday afternoon, March 31, 1934, Thomas F. Sanders and Knud Erland (1850-1947) were investigating the incessant noise of barking and howling dogs in the Erland’s Point summer community when they found three French Poodles shut inside a Packard sedan parked near the beach home of Frank and Anna Flieder. The window blinds were down in the house and there was no apparent activity.

After feeding and watering the dogs, the two men attempted to enter the house but found all the doors locked. Sanders telephoned Louis Flieder, Frank’s brother, telling him about it, and he asked Sanders to investigate further. They went back to the house and knocked on the kitchen door, but got no answer. Sanders noticed the window blinds in the sitting room were stuck halfway up. After removing the screen, the two men peered through the window with a flashlight and saw two bodies. Sanders went home and called the Kitsap County Sheriff’s Office.

Sheriff Rush Blankenship and his deputies arrived and forced open the kitchen door and entered the house. They were shocked to find six people massacred: Frank Flieder, age 45, a well-to-do retired Bremerton grocer; Anna Taylor Flieder, age 51, his wife and the wealthy widow of Clifford Taylor, a Bremerton druggist; Eugene A. Chenevert, age 51, an ex-prizefighter and vaudeville entertainer; Margaret Chenevert, age 48, his wife and a vaudeville entertainer and actress; Magnus Jorden, age 62, a retired Navy machinist mate and caretaker of beach homes on Erland’s Point; and Ezra M. “Fred” Bolcom, age 56, a Bremerton bartender.

A Deputy's Incompetence

After surveying the scene, Sheriff Blankenship left to seek help from the Seattle Police Department in collecting evidence. He assigned a deputy to protect the integrity of the crime scene at the residence.

The deputy did not carry out his assignment. “Instead he charged a crowd of 150 people 25 cents each to walk through the house and view the slaughter. The gawkers scattered gum wrappers and one woman stole the stockings off Anna Flieder’s legs” (Bremerton Sun).

That evening, the Seattle newspapers were tipped off that six mutilated bodies had been found by neighbors at Erland’s Point. Newspaper reporters and photographers were on the next boat to Bremerton. They found the crime scene unguarded when they arrived at the Flieder residence, and broke in to photograph the bodies. The reporters would have used the telephone at the murder house to phone the on-the-spot details to their respective newspapers, but it had been ripped out of the wall. Instead, reporters borrowed telephones from the neighbors. Although all of the news stories were excessively graphic, only the Seattle Post-Intelligencer saw fit to print several of the gory photographs.

News of the murders spread fast and before sunup on Easter Morning, April 1, 1934, the road leading to Flieders' beach house was congested with traffic as people drove to the murder scene. All day long, curious onlookers flocked to Erland’s Point, hoping to catch a glimpse of the sensational crime.

The Role of Luke May

The Seattle Police Department sent Luke S. May (1892-1965), Chief of Detectives and noted criminologist, to assist Sheriff Blankenship. On Easter morning, April 1, 1934, Chief May took the ferry to Bremerton and drove to Erland’s Point to collect evidence at the crime scene. When he arrived, May was surprised to find a large crowd of people surrounding the house, peering through the windows at the bodies, while police guards looked on. Sheriff’s officers assured Chief May that all of the bodies had been left in their original positions and the crime scene was untouched.

The murder victims had been bound and gagged and some had their eyes and mouths taped shut. The murder weapons, a black jack, carpenter’s hammer, stove poker, and two carving knives, were found in the house, all bloody. The killers also shot some of the victims with a .32 caliber revolver, which was never found. There was evidence that one or more victims put up a terrific fight before being killed, resulting in a wrecked living room, dining room, and kitchen May observed that at least one of the assailants had probably been severely cut with a broken bottle. There was a large amount of broken glass and blood on the kitchen floor, but none of the murder victims had sustained cuts. May took an extensive collection of physical evidence back to his Seattle laboratory for tests and analysis.

The Flieders were known as party people who would ask almost anyone they met over to their beach house to one of their parties. The prevailing theory was that it was an “inside killer,” someone who knew the Flieders' lifestyle and thought there would be a significant amount of cash on hand. Chief May concluded that the probable motive for the killings was a bungled robbery based on the facts that Anna Flieder’s diamond rings, worth $1,400, were missing, the house had been ransacked, and that the victims, who were known to carry excessive amounts of cash, had no money. And fearing identification, the robbers decided to eliminate all the witnesses.

Police failed to make any headway in solving the crime and the killers’ trail grew cold. The Seattle Times asked its readers to “Help Solve Bremerton’s Murder Mystery!” offering $1 for each letter published and $20 for the best letter outlining a solution to the case. The prize was awarded to Martin Elliott on Friday, April 13, 1934, who submitted a “detailed confession” to the mystery editor, signed “Sinisterly, The Killer.”

Breaking the Case

Little more became known about the crime until about 18 months later. In early September 1935, police arrested Larry Paulos and Joe Naples in Yakima for a Seattle burglary. The two men had previously escaped from the Seattle Police after an exchange of gunfire. But the officers got the license number of the getaway car, and knew who they were and where to find them. While waiting for “the gang” to return to their Sumner hideout, police arrested Paulos’ wife Peggy, and held her in custody.

Larry Paulos, a three-time loser facing charges of assault, burglary, and being an habitual criminal, offered King County Sheriff’s Chief Criminal Deputy O. K. Bodia the identity of the men who murdered Oregon special investigator W. Frank Akin in 1933. In return, Paulos wanted a reduced prison sentence. Paulos identified criminal associate Jack Justice, as the person responsible for arranging the hit, and Leo Hall as the trigger man.

Chief Bodia checked out Paulos’ story and it rang true. After Paulos was released from prison in 1933, he and Hall had roomed together in Seattle, and Justice was a frequent visitor. During this time, both men were dating Peggy Peterson, a local barmaid, whom Paulos later married in August 1934. Bodia gave the information to the Oregon State Police and immediately began a manhunt for Leo Hall. He assigned detectives to watch Jack Justice, Peggy Paulos, and Hall’s mother Elizabeth Hall.

The Role of Peggy Paulos

When Peggy Paulos found out her husband had tipped off police to the Portland murder, she was afraid Leo Hall would blame her and try to kill her. She went to Attorney Ralph A. Horr, a former congressman, and told him about the murders in Erland’s Point and Leo Hall’s involvement. “It was such a fantastic story that none of us really believed it at first. But the more we checked, the more it rang true” (Seattle Star).

Attorney Horr and his investigator William H. Sears, a former deputy sheriff, verified the story, and on October 19, 1935, told Seattle Police, Captain of Detectives Ernest Yoris. After learning this new information, police redoubled their efforts to catch Leo Hall.

Finally, on Wednesday, October 23, 1935, police in Portland, Oregon spotted Hall and arrested him in possession of a loaded gun. After notification, Chief Bodia immediately drove to Portland to officially identify Hall and brought him to Seattle for questioning. He also ordered Peggy Paulos and Jack Justice to be brought in for questioning.

On Thursday, October 24, 1935, Peggy Paulos gave police an official statement regarding her reluctant involvement in the Erland’s Point murders, fingering Leo Hall as the killer. Captain Yoris conducted the questioning in the presence of King County Prosecutor Warren G. Magnuson (1905-1989) and other police officials.

Peggy Peterson Paulos stated that while working as a waitress in a Bremerton café, she overheard a conversation between Anna Flieder and her friends about her recently accumulated wealth. Paulos knew the Flieders well and had been to parties at their home on numerous occasions. When she told Leo Hall about the conversation, he decided to rob the Flieders and enlisted her help. Paulos accompanied Hall to a bank where he retrieved a nickel-plated, pearl handled revolver from his safety deposit box. They took the ferry from Seattle to Bremerton and hitchhiked to Erland’s Point, arriving at about 11:30 p.m. Before approaching the house, Paulos and Hall donned masks and gloves. Hall knocked on the kitchen door, and when Frank Flieder answered it, Hall pointed his gun at him.

After entering the house, Hall and Paulos found that the Flieders were having a party and playing cards with guests in the sitting room. There were more people there than they anticipated. Hall kept them covered with his gun while Paulos tied up Frank and Anna Flieder, Fred Bolcom, and Peggy Chenevert with ice skate laces and adhesive tape. Paulos said Eugene Chenevert and Magnus Jorden, who had been out to purchase beer, arrived a short time later. With his gun, Hall herded Chenevert and Jorden into the sitting room and Paulos tied them with strips torn from bed sheets. When Anna Flieder asked to lie down, Hall picked up a carving knife, took her into the bedroom and killed her. Hall then led Fred Bolcom to the bedroom.

Paulos said she protested the killing but Hall continued, picking up a stove poker and striking at Bolcom. Paulos decided to leave and headed toward the kitchen door. Hall yelled at her to come back, and then fired his gun at her. Paulos said she ran into the backyard, losing the heel off one of her shoes. She reached the road and walked back to Bremerton, hiding in the roadside ditch when cars approached. Paulos said she met Hall in Seattle three days later and asked “Why did you kill them?” And he replied “I had to, one of them recognized you” (Seattle Star). Hall told her that Eugene Chenevert had broken loose from his bonds and they had a terrible fight with Hall receiving a severe head wound from a broken beer bottle.

The Story and the Evidence

The investigation and much of the evidence collected by Luke May at the Erland’s Point crime scene corroborated Peggy Paulos’ story. Police found the heel from Peggy’s shoe, had the ice skate laces and tape used to bind the victims, and recovered bullets from a .32 caliber revolver. The approximate times of death were accurate, the source of Hall’s pearl handled revolver was located, and a witness who worked with Hall at Todd’s Shipyard saw him on the 7:30 a.m. Bremerton-to-Seattle ferry, Thursday, March 29, 1934, with his head bandaged. Detectives also located the Seattle doctor who put 28 stitches in Hall’s scalp that same day. In addition, detectives took Peggy Paulos to Erland’s Point where she reenacted the robbery at the Flieder house. The details were perfect.

On October 29, 1935, Leo Roderick Bernard Hall, age 33, was taken before Kitsap County Superior Court Judge H. G. Sutton and charged with first-degree murder; Peggy Peterson Paulos, age 27, was charged with being an accessory to murder. In a tactical move, prosecutors decided to charge only the murder of Eugene Chenevert, rather than all six victims.

Arraignments for Leo Hall and Peggy Paulos were held in November 1935. Both defendants entered pleas of not guilty before Judge Sutton. Hall’s attorney, Everett O. Butts, filed a motion calling for separate trials arguing that Paulos would be in a position of trying to convict Hall to save herself. Judge Sutton denied the motion and set the trial for December 9, 1935.

The Trial

The trial began on schedule in the Kitsap County Courthouse in Port Orchard. Excessive news coverage of this “sensational crime” turned the trial into a circus. Hundreds of spectators flocked to the courthouse, but extra seating was limited. Judge Sutton instructed the bailiff to draw lots each morning for 84 tickets of admission for to the courtroom sessions.

The trial proceeded at a rapid pace and was over in just 10 days. Sixty-one witnesses took the stand to give testimony. The main witnesses for the prosecution were Criminologist Luke S. May, who introduced more than 50 exhibits, and defendant Peggy Paulos, who recounted her story of being Hall’s unwilling accomplice to a robbery that turned into a mass murder. The prosecution rested its case on Monday afternoon, December 16, 1935.

Defense Attorney Everett O. Butts opened his defense on Monday afternoon, accusing the Seattle Police of trying to beat a confession out of Hall and knocking him unconscious three times. He motioned for a mistrial and requested a summary judgment of acquittal, which Judge Sutton promptly denied. Attorney Butts put Hall on the stand Tuesday morning, December 17, 1935, to testify in his own defense with prepared alibis. Later that day, the defense rested its case. The prosecution called only two rebuttal witnesses to refute allegations of police brutality.

On Wednesday, December 18, 1935, Attorney Butts called most of Leo Hall’s family to testify on his behalf. Defense Attorney Ralph A. Horr called no witnesses for Peggy Paulos, relying solely on her testimony as a defense. At about 4:45 p.m. the case went to the jury.

On Thursday, December 19, 1935, at 11:10 a.m. the jury of eight men and four women returned the verdicts Hall was found guilty of first-degree murder and the jury voted for the death penalty; Peggy Paulos was acquitted of murder and set free. Although the jury was out for 16 hours, they actually only deliberated for 4 hours and 45 minutes and cast only 4 ballots. Peggy Paulos was acquitted on the first ballot. Leo Hall was convicted of murder on the second ballot. The third and fourth ballots were to achieve a unanimous decision on the death penalty.

Newspapers reported the trial’s dramatic high points as Leo Hall’s cross-examination by Special Prosecutor Ray R. Greenwood, the weeping story told by Peggy Paulos as she accused Hall of the murders, and of course, the amazing verdict. The 10 day trial was reported to have cost Kitsap County $2,500. Judge Sutton was commended for making it a fast trial thus saving the taxpayers money.

Hall's Execution

Leo Hall was taken to the State Penitentiary in Walla Walla to await execution. Hall protested his innocence, claiming that Peggy Paulos had lied. Attorney Butts appealed Hall’s verdict and filed motions for a new trial based on new evidence, but without success. The motions were all denied. Leo Hall was scheduled to hang on Friday, September 11, 1936, at 12:10 a.m. Fueled by copious news coverage, the execution also turned into a three-ring circus.

On September 10, 1936, Mrs. Elizabeth Hall and her son August “Gus” Hall flew to Olympia and pleaded with Governor Clarence D. Martin for 30 day stay-of-execution, presenting an affidavit from a person who claimed they saw Hall in Seattle the night of the murders. Governor Martin reviewed the affidavit but refused to intervene. Warden J. M. McCauley delayed the execution until 2:00 p.m. to allow Hall’s mother time to return to Walla Walla for a final visit with her son.

Attorney Butts flew from Walla Walla to Spokane seeking a federal court injunction to prevent Washington State from carrying out Hall’s execution, claiming he had new evidence. After reviewing the petition, District Court Judge J. Stanley Webster ruled that federal courts had no jurisdiction over the acts or proceedings of state court, and refused to intervene on Hall’s behalf. Warden McCauley granted Hall another stay of execution to 11:00 p.m., allowing Butts time to return to the penitentiary. In the death cell, Hall was eating his final meals and studying a library book, Poise and How to Obtain It.

Meanwhile in Portland, Oregon, Peggy Paulos, terror stricken and hysterical, hid in her apartment as the Associated Press relentlessly pursued her. She refused to come out when reporters banged on her door, shouting vague answers to their inane questions. “How do I feel?” she screamed. “My God, how would anyone feel? Oh, I wish I were dead: Please go away” (The Seattle Times).

Finally, on the evening of September 11, 1936, with more than 100 witnesses packed into the antechamber, the trap dropped beneath Hall’s feet at precisely 11:00 p.m. At 11:16 p.m. prison officials pronounced Hall dead. It was the largest crowd ever to witness an execution at the Walla Walla State Penitentiary. After two and a half years, the Erland’s Point murder investigation was finally closed.

The following day, Peggy Paulos went to work as usual at a Portland tavern to support herself and her son. Her husband Larry Paulos was serving a life term in the Walla Walla State Penitentiary for being a habitual criminal. And Jack Justice, who Peggy also helped to convict, was serving a life term in the Oregon State Penitentiary for the murder of a W. Frank Akin, special investigator for the Oregon State Governor.

A rope from San Quentin penitentiary, with noose already tied, had been purchased by the state for the execution. Prison officials said it cost the state $5.05 to execute Hall: $5 for the rope made by prison labor, and five cents for the electricity to spring the trap.