On March 15, 1937, Governor Clarence D. Martin (1884-1955) signs into law State Bill 189 outlawing dance marathons statewide. Dance marathons are Depression-era human endurance contests in which couples dance almost non-stop for hundreds of hours (as long as a month or two), competing for prize money.

The bill was introduced by Democrat Earl W. Maxwell (1897-1958), state senator for the 31st District (northern Pierce County, Southern King County). Maxwell, who was at the time Vice President of Pacific Coast Railroad Company, served in the state senate from 1933 to 1944.

Dance marathons became popular during the 1920s as part of a jazz-age fad for setting world records. Initially couples danced nonstop (with no rest periods at all) until only one couple remained on the floor. Such a contest, while extremely tiring, could last at most several days. The contests, however, quickly evolved into performative events in which contestants, while still required to dance around the clock, were given 15-minute rest breaks every hour. This change allowed the strongest to endure the grueling toil for weeks or sometimes months, dancing upwards of a thousand hours straight.

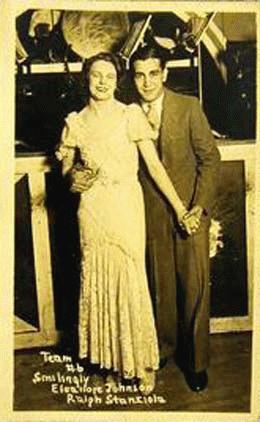

The contests were mounted by professional promoters with a contestant base made up of hopeful, sometimes desperate amateurs and seasoned professionals known as horses for their ability to go the distance. Prizes, usually between $500 and $1,000, were awarded to the top finishers. The events became a hallmark of life in America during the Great Depression.

Dance marathons included vaudeville-type entertainment and grueling elimination events. During these elimination events the exhausted contestants were required to race sprint and derby style, sometimes blindfolded and/or chained to their partners, until a contestant collapsed and was eliminated. Audience members paid 25 cents to root for their favorites.

Dance marathon promoters often called the events walkathons in attempt to make them sound more wholesome. Despite this obfuscation, the marathons provoked great protest from churches, women’s groups, and police officers. Churches and women's groups objected on moral grounds (the contestants' full-body hugging dance positions as they dragged one another around the floor for hours were a far cry from social dance positions) and for humanitarian reasons (the rigors of a dance endurance contest were felt to degrade the human spirit and morals of the contestants, and by extension of the community). Police officers felt that the marathons attracted a criminal element to their towns, or at the very least that marathon promoters were only interested in short-term gain at the expense of the community.

Many towns nationwide passed anti-dance marathon ordinances, including Seattle in 1928 and Bellingham and Tacoma in 1931. These ordinances had the effect of driving the events onto the fringes of towns, just outside municipal jurisdiction. Seattle and Tacoma dance marathon fans, for example, could still attend the events in Fife as late as August 1936.

State legislation, which became increasingly utilized across the nation as the 1930s wore on, could prohibit dance marathons statewide in one fell swoop. In 1931 Texas became probably the first state to pass such legislation. Maine, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and New Hampshire followed suit (Martin, p.147).

Washington’s 1937 law read, in part, “114-93 Endurance Contests Prohibited. It shall be unlawful for any person, firm, corporation, or association of persons to conduct, carry on, manage or maintain, or to cause or permit to be participated in, or aid or assist in the conducting or maintenance of, any public so-called ‘marathon dance,’ ‘walkathon,’ ‘endurathon,’ ‘speedathon,’ or any public endurance dancing, walking, skipping, jumping, sliding, gliding, rolling or crawling contest or exhibition under any other designation or name, or any similar exhibition or contest of human endurance in dancing, walking, running, skipping, jumping, sliding, gliding, rolling or crawling within the state” (Pierce).

The law remained in effect until repealed in 1987.