On December 31, 1915, Seattleites celebrate the last New Year's Eve before Prohibition takes effect. The mood is one of somber pathos. Washington state allows liquor sales until midnight, when Prohibition begins. Washington joins 18 other dry states that have outlawed the sale and manufacture of intoxicating liquors.

Seattle's Somber New Year

In Seattle, one of the largest cities in the nation to go dry, there were large crowds on the streets but the enthusiasm and boisterous crowds of previous New Year's celebrations were lacking. This year the loudest noise on the streets was made by hawkers selling horns and cowbells.

“Down below Yesler Way, where hilarity and rioting was to be expected ... there was more of pathos than of hilarity” (The Seattle Times).

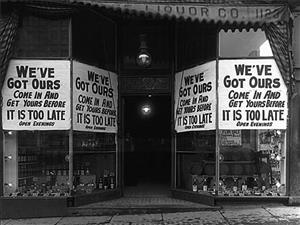

Signs of the Times

Signs on the closed saloons said it all: “Died December 31, 1915,” “Gone but Not Soon to Be Forgotten,” “Stock Closed Out -- Nothing Left,” “A Happy and Dry New Year,” “Closed to Open Soon as a Soft Drink Emporium” (Seattle Post- Intelligencer).

In Seattle the previous year, some 315 saloons were open for the New Year's celebration but on December 31, 1915, only 200 opened. In 1915, many saloons had closed because their leases expired, or the saloon keepers did not want to renew liquor licenses, or they had run out of hard liquor, or they were afraid of general destruction to furniture and fixtures by customers. Saloon men admitted that patrons had been cutting back on their drinking since the Prohibition initiative was approved in 1914.

On New Year's Eve, as liquor ran out or got low more saloons closed, and after snow began to fall others closed to let staff get home early. By 10 p.m. no more than 75 bars and saloons remained open. Those still open were very busy selling only straight drinks, no time to mix drinks. By midnight all the saloons were legally required to close, and “[t]he New Year had arrived with its soda pop” (Seattle Star).

The mood was definitely different at the Woodinville, Washington, branch of the Good Templars, whose members had fought successfully for Prohibition. They had a great New Year's Eve celebration.

All over the state, the market for moonshine booze began a steady expansion. In 1917, the Spokane County prosecutor complained that the soft-drink shops were worse than the old time saloons: Booze was plentiful. In Tacoma, the longshoremen demanded that police clean up the drug stores and soft-drink shops, where beer and hard liquor were easily obtained.