On Wednesday afternoon, November 25, 1998, an explosion and fire erupts in the coking plant at the Equilon Puget Sound Refinery in Anacortes, killing six refinery workers who were attempting to restart the delayed coking unit following a power outage. The tragedy is the worst industrial accident since the Department of Labor and Industries began enforcing the Washington State Industrial Safety and Health Act (WISHA), more than 26 years ago.

On the evening of November 23, 1998, a powerful Pacific storm blew into Western Washington with gusts to 60 mph. The winds created power outages throughout the region mainly from downed trees hitting power lines. One of the storm's victims was the Equilon Puget Sound Refinery in Anacortes, which lost total electrical power for approximately two hours, interrupting critical refining operations and laying the groundwork for the subsequent explosion and fire.

Corporate Biography

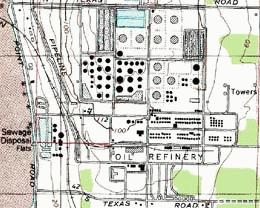

The oil refinery began in 1958 as a Texaco plant on March Point near Anacortes. On January 16, 1998, Equilon Enterprises was formed by a merger of the marketing and refining operations of Shell and Texaco. On July 1, 1998, the company renamed the Texaco Refinery, the Equilon Puget Sound Refining Company. In January 2002, Shell purchased the plant in a corporate wide restructuring, and the plant was renamed Shell Puget Sound Refinery. It is now (2003) part of Shell Oil Products Group US.

The refinery is the largest employer in Anacortes with about 375 people and 100 contract workers and has an annual payroll of $27 million. It refines 143,000 barrels of Alaskan North Slope and Canadian crude oil per day into gasoline, jet fuel, diesel fuel, propane, petroleum coke, and sulfur.

The Problem of a Power Outage

Refinery workers consider shutdown and restarting operations to be two of the most dangerous times in a refinery's operation. And now, due to the power outage, the delayed coking unit needed to be restarted.

The delayed coking unit consists of two huge pressurized stainless steel drums six stories tall. The coking process is a 16-hour cycle during which crude oil, heated to 925 degrees Fahrenheit, is pumped into the steel coking drums. The intense heat and pressure "crack" the oil molecules, producing vapors that are siphoned off the top and piped elsewhere for further processing. The remaining material crystallizes into a charcoal-like substance called petroleum coke, which has other industrial uses. The drum is injected with steam and water in a cooling process. Once the drum is cooled, the process is turned over to a specialty contractor (Western Plant Services). The coking drum is unsealed at the top and bottom and the coke residue is cut with a high-pressure water drill and removed. The drum is then resealed and prepared for another cycle.

Errors

Instead of the normal water-cooling process, Equilon plant managers decided to leave the coking drum to cool naturally for 37 hours before opening the drum. The Department of Labor and Industries estimated that 236 days would have been required for the ambient air temperature to cool the drum before the material could be safely removed.

On November 25, 1998, Equilon plant managers issued Western Plant Services, the specialty contractor, a "safe work permit" authorizing them to open the coking drum. Sensors measured the temperature near the drum wall but could not measure the heat at the core. The workers, wearing oxygen masks, unbolted and safely removed the top head. At about 1:30 p.m., the bolts holding the bottom head in place were removed, and an hydraulic lift began to lower the head from the bottom of the coking drum. The men expected to find a congealed mass of crude oil residue, but the unit was far hotter than anyone thought.

The Tragedy

Immediately, a pocket of hot liquid fuel broke through the crust of cooled residue and poured from the drum. When exposed to oxygen, the superheated oil exploded into flames engulfing the two refinery workers operating the lift and spewing off the second level of the unit onto the four workers below.

Witnesses said they heard an explosion, and saw a large plume of black smoke rise up from the refinery followed immediately by a ball of fire which rose several stories high. A few minutes later, the refinery's "wildcat whistle" sounded, signaling an emergency. The blast was felt several blocks from the refinery and knocked out electrical power to the neighborhood. As the huge cloud of black smoke began drifting toward Anacortes, city officials, worried that the smoke was toxic, rushed to schools and businesses, advising people to remain inside. The Skagit County Department of Emergency Services determined the smoke was not toxic and the notifications were stopped.

While battling the blaze, Puget Sound Refinery firefighters attempted several times to search for survivors but were driven back by the intense heat. When the fire was finally extinguished and the smoke cleared, firefighters discovered that six refinery workers had perished in the explosion.

The victims, employed by Equilon, were Ronald J. Granfors, age 49, a foreman in the Crude Processing Department, and Wayne E. Dowe, age 44, a refinery operator. The victims, employed by Western Plant Services, were David Murdzia, age 30, a supervisor, Warren Fry, age 50, Theodore Cade, age 23, and James Berlin, age 38, who were coke-cutters. Skagit County Coroner Bruce Bacon said that autopsies concluded the men died from smoke inhalation and also suffered burns.

Investigation and Settlement

The Washington State Department of Labor and Industries immediately dispatched three investigators to the refinery. It was the worst industrial accident since the Department of Labor and Industries began enforcing the Washington State Industrial Safety and Health Act (WISHA), established in 1973. The investigation into the deadly mishap lasted six months. The investigators concluded that the accident was caused by a cascading series of mishaps and errors, and could have been prevented. Most notable was the decision by plant managers to allow the coking drum to air-cool for only 37 hours instead of using the normal water-cooling process.

In early May 1999, Equilon Enterprises of Houston, the owner of the refinery, approached the Department of Labor and Industries, asking to negotiate a settlement. On May 26, 1999, Equilon, agreed to a record $4.4 million settlement package. It was the largest monetary settlement ever reached as the result of worker safety and health investigation. The agreement included a $1.1 million fine; a $1 million donation to the Fallen Worker Scholarship Fund, established on behalf of Equilon employees' families; $1 million to establish a Worker Safety and Health Institute at a state institution; a $350,000 donation to the City of Anacortes Fire Department to purchase a new fire engine, and $350,000 for an independent safety audit of the refinery. Equilon also agreed to fix all identified deficiencies.

Prior to the agreement, the company installed a new $575,000 remote-controlled system at the delayed coking unit that allows operators to unseal the giant steel drums from a shed 200 feet away. The company also designed and installed a $30,000 natural gas backup system to create steam for purging the unit in the event of a power failure.

In the agreement, the Department of Labor and Industries agreed not to classify the two violations issued to the Equilon Puget Sound Refinery as "willful" (implying negligence), the most serious classification under the Washington State Industrial Safety and Health Act (WISHA). Instead, the violations were designated "unclassified." It was the equivalent of a no-contest plea, with no admission of guilt or wrongdoing by the company.

On January 19, 2001, a $45 million settlement was reached between Equilon Enterprises and the families of the six men killed in the Puget Sound Refinery accident. The settlement, which came 10 days before a trial was to begin in Skagit County Superior Court, was the biggest single cash settlement in a wrongful death lawsuit in Washington history. Under the agreement, Equilon and their insurers paid $45 million into a trust fund for the families of the six victims.

In a written statement to the court, Equilon Enterprises accepted responsibility for the accident. "We are very sorry for the loss of life and the pain and suffering of these families. While nothing can bring back the men we lost, this agreement avoids the pain of a difficult trial and enables families, our employees and the community to begin to heal." According to the families involved in the wrongful death lawsuit, Equilon's admission of responsibility was as least as important as the large settlement.