Dr. Gary Anderson has researched the tragic 1944 death in Germany of Aberdeen native Lt. Theodore Nielsen. With the assistance of Historylink.org and Dave Barber of the City of Seattle, Dr. Anderson was able to locate Lt. Nielsen's family and to complete the documentation of this story. Dr. Anderson teaches at Zeppelin University in Friedrichshafen, Germany.

An American Pilot From Aberdeen

Nine hours and thousands of miles away from Aberdeen, Washington, a pall of blue cigarette smoke lingers lazily above the Stammtisch (table for regulars) in Gasthaus Engel (Angel) in the rustic hamlet of Haid, a roadside village two kilometres from the spa city of Bad Saulgau, Germany. The friendly Schwabian beer connoisseurs bend over another half-litre of thick German beer and banter about the usual themes: cars, football, politics. Undoubtedly, this 150 year-old former brewery has heard its share of discussion. But one theme still casts a special and concerned hush over the table: the fate of a young American pilot 60 years ago.

For here, a short distance between Gasthaus Angel and a large Catholic convent, and a mere football field away from a roadside bronze crucifix, an unholy event occurred in a tiny fleck of forest called "Haid Stöckle" on August 9, 1944: one of Aberdeen’s most promising young men was brutally murdered, a crime that casts a shadow of sadness over this peaceful farming village some 60 years later.

Aberdeen’s Best and Brightest

All that is left today to remind one of Aberdeen’s direct link to the city of Bad Saulgau is a string of numbers on dusty boxes in the county archives: Box AA VIII/126. Local historians have mentioned the case in various books over the years, and the Bad Saulgau newspaper even mentioned the name of O-75665 in their 1995 commemorative edition marking the 50th anniversary of the end of World War Two: Lt. Theodore D. Nielsen.

Born the seventh of nine children to Peter and Rhoda Nielsen of Aberdeen on June 10, 1922, "Ted’s" youth was joyous, according to information provided by his niece, Mrs. Klancy deNevers. His father, Peter M. Nielsen, who owned a pharmacy in Aberdeen, emigrated from Denmark in the late nineteenth century. Together with his wife Rhoda, he settled in Washington state after short stints in Baltimore and Minnesota. A sprawling two-story house on K Street, complete with "porches, a balcony, a sleeping porch and a full attic and basement" provided the Nielsen children hours of happiness and room to explore. A relative recounts, "there were outings, picnics, kite flying, wagon racing. The children ran free in the neighborhood and in the woods above the town."

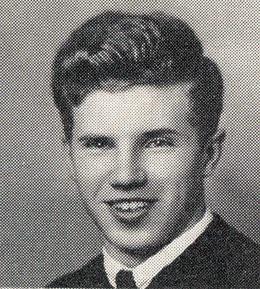

A photo of Ted Nielsen in the Aberdeen paper in August 1944 shows a strongly built young man in his early twenties. As a youngster, said one family member, he was "pudgy ... as he moved into short pants and sailor outfits ..." Ted Nielsen was blessed not only with physical stature but also inquisitiveness and abundant desire to learn -- a real "go getter." At age 14, Ted was publishing cards and letterhead on an old manual printing press that he taught himself to use. His goal was to enter the printing industry following the footsteps of brothers-in-law Kearney Clark, editor of the Grays Harbor Post, and Alex Dunsire, printer at Quick Print Company. In high school he was active as a young Rotarian, tennis player, tenor-baritone in the Glee Club, the Senior Boy Scouts, the Debating Club, and, last but not least, as trombonist in the Weatherwax High marching band.

Following graduation, Ted started work at Quick Print Company. But his dream to translate an interest in printing into a lifetime profession was interrupted by the looming war. Like so many young men in those dark days, Nielsen carried the civic-mindedness that characterized pre-war America into military service, joining the National Guard in Grays Harbor County in September 1940. At first it appeared that World War II might never come closer to Ted Nielsen than the 248th Coast Artillery Battery at Ford Worden, where he served until September 1942. Not satisfied to "sit out the war" on the sidelines, the ever-ambitious Ted sought and qualified for flight training in September 1942, in Santa Ana, California.

In a March 1943 article in the Aberdeen Daily World, air cadet Nielsen described life in Santa Ana as tough and disciplined -- a mixture between military drill and aviation science. Ted’s wings were delayed due to a bout with scarlet fever and flu, which left him hospitalized. With flight training behind him by fall 1943, Nielsen moved to Luke Field, Arizona, for fighter plane training.

There he met and married Artie Nichols, a native of Kentucky and, no doubt to Ted’s delight, "herself a licensed pilot." A short honeymoon at Lake Louise in Canada was all the war permitted. Ted reported back to Santa Ana to train in P-38s in Squadron #36. From there he wrote of his flying exploits, clearly loving the life on an aviator: ‘This P-38 is a pretty sweet ship but it takes a man with a strong arm to wring (it) out -- the other day we were letting down from 34,000 feet ‘cause my oxygen failed we clocked 450 MPH at 28,000. When that is calibrated for altitude and temperature it is better than 750 MPH. And just off the record I would like to say that ain’t hay.’

"Looking Jerry in the Face"

By this time, Nielsen was ready for combat. In March 1944 he was deployed to the 364th Fighter Group, 384th Fighter Squadron based in Honington, England -- "a swell bunch of fellows and damn good pilots … (I will) learn a lot if I listen to them and I’m really going to," he wrote.

Life in England impressed the young man from Aberdeen. For the first time he experienced first-hand the brutality of German bombing raids. He wrote about visiting bombed-out cities and gave John Bull, a nickname for Britain in those days, "a hell of a lot of credit and praise for the way he has stood up and fought back."

To his sister Dorothy Clark, who lived in Florida, he wrote about life in Britain:

"Here in England it is very different than at home, the towns seem like little hamlets and yet are larger by population than one of our cities. The small towns (under 5,000 people) are like farms and rural communities. The land is under all sorts of cultivation with every bit of space in use — the country is amazingly clean compared to home. No trash cluttering up the RR right of ways. The roads are very winding and lined with hedges — very quaint to say the least. The British money seems very queer compared to ours."

But there was little time for relaxation. Lt. Nielsen wrote, "I am now looking Jerry in the face." Shortly after his arrival in April, he began flying missions in P-38s over Germany, strafing targets of opportunity, including one locomotive. On D-Day, June 6, 1944, Ted flew long hours patrolling the coast of Normandy. Four days later, he was awarded the Air Medal and, on July 8, 1944, promoted to First Lieutenant.

As the war grew longer, so did the missions. To his sister he described the tiring effects of flying long-range escort missions deep into the heart of Germany. After one five hour mission he wrote: "Just try to sit in the same position for that long."

Nielsen was slated to return to Washington by the fall of 1944, a prospect that gave him new hope and energy. And his young heart planned on the future despite the brutality and danger surrounding him. In a letter to his sister Louise Clark, Nielsen dreamed of "coming home in the fall, to be with Artie, buy a house and have a big family." He wrote: "I’m going to come back and see that baby of mine -- until I do the kids there have got a job to see that Artie is well and cared for…we should have a home shortly after I return. We are thinking of settling in California and hope to be settled by October or November."

And he wanted to have a big family. To his sister Louise he wrote in March 1944: "Give me a little time sis, I’ll have you matched in a couple of years -- I want to grow up with my kids --that’s the fun of having a family."

Pilot Chase

By 1944, all of Germany was reeling under the heat of the Allied advance. Hardly a city or village remained untouched by the relentless Allied air attacks. At first the industrial centers were damaged, then mercilessly obliterated. The introduction of long-range fighter escorts by 1944, but especially the advent of the Mustang, dubbed the "Cadillac of the Skies" in the 1987 film The Empire of the Sun, allowed pilots like Nielsen to escort heavy bombers to their targets and, ammunition and fuel permitting, search for targets of opportunity. These so-called "Little Friends" brought the war to millions of Germans living in rural areas previously untouched by the Mighty 8th Air Force and the Royal Air Force.

By the time of Lt. Nielsen’s unexpected arrival over Saulgau, the town, with its tiny hamlets Haid, Bogenweiler, and Convent Siessen, was groaning under the stress of the war. With a pre-war population of 5,000, Saulgau had swollen to more than 10,000 by 1944-1945, mostly refugees, forced laborers at the V-1 rocket plant, concentration camp internees, and other lost souls from the bombed out cities. Allied aircraft zoomed overhead on their way to Stuttgart, Munich, or Ulm. Friedrichshafen, home to the Zeppelin airships on Lake Constance, a crow’s flight from Saulgau, had been reduced to ashes, as had nearby Ulm and Stuttgart. Nothing was spared: cars, trains, people working on meadows -- everything became a target by the end of the war. In all, some 600,000 German non-combatants died as a result of the air campaign.

Life in Germany had become the living Hell. By autumn 1944, the Saulgau daily newspaper chiefly comprised three main sections: 1/3 about great victories in Russia and France; 1/3 about Allied "terror pilots" who committed "terror raids" on German cities; and 1/3 obituaries of young boys who "gave their life for Führer and Vaterland." The Supreme Command Staff of the Armed Forces issued the following directive on July 5, 1944:

"According to press reports the Anglo-Americans intend to subject to air attack small localities without any war-economic or military values, as a reprisal against the V-1. In the event this report proves true, the Fuehrer orders that notice be served via radio and the press that every enemy aviator who is shot down while participating in such an attack is not entitled to treatment as a prisoner of war but that he will be treated as a murderer as soon as he falls into German hands."

Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, in an "editorial" in the Nazi mouthpiece Volkischer Beobachter, wrote that "very soon a great pilot chase will start in Germany" and suggested that downed pilots should be lynched. Hitler’s memo on the issue stated, "pilots are to be shot without danger of court martial," and SS Chief Himmler warned German citizens that helping pilots, what he called "falsely understood compassion," would land them in a concentration camp. Lynch mobs, shootings, beatings, and public humiliation of downed aviators became an ugly routine across Germany.

One B-17 crewman, shot down near Frankfurt, recalled: "I think most of the fellows will tell you that the German civilians were a greater threat to our ever reaching prison camp than the soldiers ... One of their pet calls was ‘Hang the bastards!’ in perfect English, too." The SS was particularly gleeful in carrying out these "orders," in many cases taking pilots from civilians, who sometimes offered them protection, and the often humane German Air Force (Luftwaffe), and executing them on the spot. In all, an estimated 200 or more pilots were murdered. So was Germany in 1944.

Goldfish Blue Flight

On August 9, 1944, Lt. Nielsen flew third position in "Goldfish Blue flight" in P51-D 44-13766, together with wingman Lt. Frank T. Kozloski, on a long-range bombing raid to Munich. Flying south of Stuttgart on a search and destroy mission, the pilots of the 384th Fighter Squadron made their way through misty conditions and broken clouds until finally discovering several gun positions to strafe. Flying to the immediate left of Nielsen, Kozloski was "occupied with a good target" and had little opportunity to notice the flak that engaged Lt. Nielsen’s Mustang. Only later did Kozloski notice that Nielsen was in trouble:

"On coming off the target we started to re-form. I noticed that Lt. Nielsen was behind so investigated. On doing so I discovered that he had no canopy. He also had his left hand holding his face. I could not contact him by radio, so flew in front of him and set him on course. I then flew back of him, protecting his tail. We were then about 100 feet from the ground. I tried to get him to climb and after 15 to 20 minutes we reached 3500 feet. I was then in back of him. His airplane started to smoke. Fire appeared and the ship became ablaze. He went into a spin and I circled. A parachute opened and I circled until he reached the ground. He picked up his chute and as I buzzed him, he waved and then ran into the woods nearby. I then set course for home."

Kozloski later reported that Nielsen had jumped 50 miles southwest of Stuttgart, somewhat southwest of the city Rottenburg. In fact, Nielsen landed in a small wood some 60 statute miles south-southeast of Stuttgart, approximately 40 air miles southeast of Rottenburg.

Because air raid warnings were sounded, a good number of Germans also saw Nielsen’s jump. "I noticed, that an airplane trailing smoke had to make an emergency landing. At the same time, I noticed that the pilot jumped out with the parachute," reported one witness. Klemens Ermler, a 37 year-old produce handler, was working in a nearby field shortly before noon when Nielsen’s Mustang crashed some 500 meters from his position. Mounting his bicycle, Ermler rode first to the plane, then to the place where Nielsen’s parachute landed, in the corner of a small wood roughly 200-300 meters from the wreck itself. Ermler rode further, finally spotting Nielsen "run into the woods and take cover behind a tree."

He approached the edge of the wood where Nielsen was lying behind a small pine. Realizing that there was no escape, Nielsen walked out of the wood with his hands over his head and surrendered to Ermler. Ermler reported that he had a few light abrasions over the eye, and, when asked about his nationality, responded "American." It was then, before Ermler and Nielsen could exchange any further words or gestures of understanding, that a car approached carrying two uniformed soldiers and a plain-clothed SS man.

The Banality of Evil

Friedrich Wilhelm Altena, Otto Fuhrmann, and Joesph Hoelzle were Hannah Arendt’s archetypes of the "banality of evil" (as described in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil) With the rest of Germany’s able-bodied soldiers assigned to the front, petit bourgeoisie like these remained behind to become, in popular German parlance, Schreibtischtäter, or "desk-top criminals." All three members of the SA or SS, this lackluster gaggle was a far cry from director Leni Riefenstahl’s depiction of the Aryan super race.

Freidrich Wilhelm Altena made for an unlikely SS Oberhauptsturmführer. Slightly-built, nearly bald, recently divorced and suffering from the effects of severe recurring tuberculosis and a botched appendix operation, the 42-year-old Altena had worked his way through the ranks of the SA, then the SS, to become an SS major by the early 1940s. Like many of the NSDAP’s most devout, Altena belonged to the disenfranchised soldiers of World War I and the postwar years who felt lost and betrayed in the new Weimar democracy.

In 1930, only two years after being mustered out of the army on account of tuberculosis, Altena joined the Nazi Party. His primary task, far from the feared image of the SS, was to locate living quarters for Aryans returning to the Reich from the occupied lands to the East, mostly Russia, Poland, and the Sudetenland. Records show that, despite his position, he never attended Nazi rallies or meetings. He merely paid his annual dues. He was never on the front; he never knew the face of battle. The only enemy soldier that he saw eye-to-eye in World War II was Lt. Nielsen.

Accompanying the Oberhauptsturmführer on that fateful day were two SA men, Otto Fuhrmann and Joseph Hoelzle. Fuhrmann, a "commercial employee" by profession and commander of the resettlement camp in Saulgau, made an equally unimpressive figure in his brown party uniform. From Fuhrmann’s list of ailments, ranging from near deafness to being able to look only to the left with a clear vision of 25 meters -- the result of a World War I wound -- it is clear that the resettlement camp at the Catholic Convent Siessen, where Altena had been holed up since May recuperating from an operation and tuberculosis, was not a high-level assignment of enormous responsibility. Hoelzle, part-time tailor, part-time SA man, was the only Saulgau native.

It was these three Wagnerian specimens of the superior race that raced headlong down a small road from Convent Siessen to apprehend a young and frightened American aviator dressed in a flying suit and wearing the white scarf of the 384th squadron.

Back at home, news of events in Germany came slow. Letters sent to Ted by his brother-in-law in California were returned stamped with the ominous red message: "Missing." In late August, Artie, now living with her new-born daughter near Ted’s family in Washington, received notice that her husband was missing in action. A short article in the Aberdeen Daily World on August 31, 1944 stated briefly:

"Lt. Theodore Nielsen of Aberdeen was reported missing in action August 12 in the European Theatre, relatives learned today. A 1940 graduate of Weatherwax High School, the flier piloted a fighter plane ... Lt. Nielsen is the son of the late Mr. and Mrs. P. M. Nielsen of Aberdeen. He has a sister, Mrs. Kearney Clark of Aberdeen."

An October 7, 1944, article in the Grays Harbor Post raised spirits.

Lt. Theodore Nielsen May be Hiding in Nazi WoodsLieutenant Theodore Nielsen, recently reported missing on a bomber escort over Germany, may at this time be hiding out in a German forest near the present Allied fighting line. This possibility was revealed in a letter received last Saturday by Mrs. Artie Nielsen from the Headquarters, Army Air Force, Washington, D.C.

The forest hid not Lt. Nielsen, but rather, a sad legacy. What happened in this tiny forest, a stone’s throw from the hamlet of Haid and under the watchful eyes of the Catholic Convent Siessen, causes heads to hang in a mixture of sorrow, disbelief, and anger in Haid to this day, nearly 60 years after Lt. Nielsen’s final flight.

The Trial

For more than two years after encountering Lt. Nielsen, Altena, a POW since September 1945, was transferred from hospital to hospital across Germany, first to the Harz Mountains, then to the British Zone in Oldenburg. Lying in his bed in the forenoon of January 13, 1947, Altena noticed an American officer enter the room and approach his bunk. He asked if Altena had knowledge of the events in Haid during August 1944. Altena offered up his version of the story. Soon a German policeman arrived, then the American officer once more, and, several days later, Altena was transported to an "internee hospital" in the northern city of Rodenburg. Back on his feet by mid summer, Altena was formally charged "with unlawfully encouraging, siding, abetting and participating in the unlawful killing of a member of the United States Army, a surrendered prisoner, at Saulgau, Germany, on or about 9 August 1944." Altena’s past had finally caught up with him.

Altena’s colleagues had less time to reflect on the events of that day. In little more than a month after the German surrender, Hoelzle and Fuhrmann, but also the nurse and doctor who treated Nielsen, Klemens Ermler, a cattle dealer named Josef Holzmueller who examined Nielsen, and even Altena’s housemaid, were summoned to provide testimony. In the afternoon of September 17, 1947, Fuhrmann, Holzmueller, and Dr. Max Stiegele were loaded into an army truck and transported from Saulgau to Dachau -- a grueling trip even by today’s standards.

The United States versus Friedrich Wilhelm Altena, case number 12-1068, was only one of hundreds of trials conducted against war criminals in Dachau and Nuremburg following the war. Due to the case load and other political considerations, the pace of these tribunals was blistering by today’s standards. U.S. v. Altena was no different, heard in its entirety from September17-19, 1947.

After the haggard witnesses arrived, the court reconvened at 1:30 p.m. on the 18th. Klemens Ermler was the first to take the stand. After describing Nielsen’s surrender, Ermler stated that he had been alone with Nielsen before Altena’s car arrived, and that the latter shouted at him "get out of here!" Ermler continued: "At first I wanted to refuse, then I grasped the situation and I realized that my own life was in danger ... so I turned back in the direction of Haid and moved off ... if I hadn’t gone away he would have shot me down, I’m sure of it ... because he asked me very brusquely to leave and his manner got more abrupt all the time."

After the third challenge, Altena pulled a small caliber pistol from his coat pocket. "I moved off but looked back sort of towards the half right over my shoulder and then I saw him with the pistol in his hand." What happened next occurred within seconds. "I was so scared," testified Ermler, who moved rapidly away from the scene. Ermler recounts how Nielsen and Altena stood some four meters (about 13 feet) apart, and seeing Altena aim the pistol at Nielsen who, before the first shot rang out, raised his hands to his chest in a prayer-like position and "begged and implored" for his life. Three, perhaps four shots rang out, all at prolonged intervals. Ermler, now tremendously excited and scared, fled the scene without his bicycle, walking around "afterwards ... so upset ... that I couldn’t even tell who was the next one there."

Otto Fuhrmann, SA man and camp commander at Convent Siessen, and his brown-shirted comrade Hoelzle, were also sent off by Altena, only in a different way. They were dispatched from the scene to look for another downed pilot, who, according to Altena, had also come down in the wood. This turned out to be untrue. Thus, at the time of the shooting, neither Ermler, Fuhrmann, nor Hoelzle were close enough to hear any conversation between Altena and Nielsen (Altena spoke some English). Fuhrmann testified that he and Hoelzle had proceeded "out of the wood and up towards the road ... maybe 15 to 25 meters ... and then we suddenly heard shots." Fuhrmann also recalled hearing a volley of shots, "two quick ones, maybe, or three, a pause after that, and then when Hoelzle and I came back a few more, in two volleys ... there was some interval."

In the meantime, a considerable crowd had gathered near the scene of the shooting. Some were said to be armed and angry, wielding various weapons including small caliber rifles. Most were simply curiosity seekers hoping to catch a glimpse of the plane or pilot. A good number were children.

The first person to go between Altena and Lt. Nielsen was Josef Holzmueller. Holzmueller testified that he was not interrupted or addressed by Altena as he knelt beside Lt. Nielsen to examine his wounds. He reported that Nielsen "made painful outcries" and heard Altena say to the crowd, "Well, that beast tried to attack me." Apart from Holzmueller, who left about 20 minutes after the shooting, Altena allowed no one except a policeman to approach Nielsen, not even nurse Maria Bullinger who, having witnessed the Mustang’s crash, had rushed from the hospital to the scene. After finally gaining access, Bullinger ran to Nielsen and knelt beside him. Taking his pulse and examining his wounds, she concluded that he was "seriously wounded, doomed to death." At the same moment, Altena approached her and ran her away from Nielsen, and "told me not to soil me (in German, to defile one’s self) with this blood."

From the very outset, Altena never denied shooting Nielsen. From the day of the shooting until well into the 1950s, when the world seems to have lost track of him, Altena stuck to his story: that Nielsen had tried to attack him using a blue-handled dagger concealed on his right thigh. He stated:

"Fuhrman and Hoelzle were with me or behind me. When I had walked some 40 to 50 paces through the wood suddenly from behind a tree a flyer — you could recognize him by his flyer’s combination — stepped out from behind that tree at a distance of about 4 to 5 paces away and walked towards me. I was jumpy at first and said, ‘step up,’ and I held up my pistol. Now the whole story I am about to you is in a matter of seconds. I turned to the right and said to him, ‘you go back a little, there are some more coming.’ As I was turning towards the right and talking to the camp commander (Fuhrmann) who had been left slightly behind me, I saw out of the corner of my eye a movement, and I still see within my field of vision that this man is moving. So I spin around to the left and I see this man taking a downward movement with his right hand. He was twisted and turned towards the half right, and I saw that he almost touched the handle of his dagger which he had on his right trouser leg ... At the very same time I just took a pot shot at the direction in which he was reaching. I shouted, ‘halt’ at the same time but as I said it went all like a flash ... I was upset and I turned around to them (Fuhrmann and Heolzle) and said, ‘Did you see that, did you see him reaching, wanting to attack me, did you see him reaching for his dagger?"

Throughout his testimony, Altena portrayed himself as the man in charge on that day, but also as a person misunderstood and treated unfairly by the people of Saulgau and betrayed by his two comrades, Fuhrmann and Hoelzle. Altena claimed that he first helped people at the hospital and saw that they took cover when the air raid began. Then he drove to the plane where he urged parents and their children to stand back from the burning wreckage. After the shooting, he encouraged Holzmueller to examine Nielsen -- even spoke to Holzmueller about how to best handle the wounded aviator -- a claim that Holzmueller flatly denied. He claimed to fend off the ever increasing crowd, which was there, he thought, to harm Nielsen or to take his possessions. Some, he noted, were armed and meant to harm the pilot: "... I thought maybe that as hyenas of the battle ground they were looking for some souvenirs or some loot." A strange thought for a man who had just looted the life of a young aviator.

He claimed to have ordered an ambulance and that he allowed Ms. Bullinger to treat Nielsen after ascertaining that she was not there to steal his white squadron flying scarf. He even claimed to place the pilot’s boots carefully in the ambulance before he, Fuhrmann and Hoelzle returned to the convent.

As for the knife, Altena claimed that a police lieutenant driving a blue Opel Model 4 took possession of the weapon shortly after the shooting. He testified:

"This police officer went through the group of people to the flyer and he took a look at him and he took over the weapon. I saw with my own eyes that the handle of the weapon was blue, it was the color of the sky and that … it was double edged. The police officer had this weapon in his own hand and later on — this happened when the ambulance arrived — I saw that he walked up to his car, opened the car and I saw with my own eyes how he threw the weapon into the back seat of the car."

However, the only other person to get close to Nielsen before the policeman arrived was Holzmueller who found no knife near or on Lt. Nielsen. Neither Fuhrmann nor Hoelzle, who arrived on the scene seconds after the shooting, saw a weapon on or near Nielsen. Oddly, for a man who claimed to organize and control the entire event, Altena could not remember the name of the policeman who he never saw again. Neither knife nor policeman was found by American officials after the war.

Conveniently, Altena also claimed to have heard very little if anything of Goebbel’s lynch mob directive. For a man who had met Himmler, had a close relationship with SS General Lorrance of Stuttgart, and was director of all resettlement camps in the Third Reich, Altena, strangely, had heard nothing much about Hitler’s order to shoot Allied pilots. Altena claimed to have first heard of such orders long after the shooting, and that he never listened to propaganda on the radio. Trial excerpts reveal an amazing double-step by Altena:

Q: Did you ever hear Goebbel’s propaganda on the radio?

A: I merely listened to the radio. When I did it was to take in some news and when I was out in one of the rest rooms ... I liked to listen to the music.

Q. You never heard the propaganda, is that right?

A: Well I heard it maybe. It was talked about but I couldn’t say now that I listened to it or that I was interested in it.

Q: Then you may have heard his talks about the treatment of enemy fliers, or read his writings, is that right?

A: No, I didn’t.

Despite reporting being very upset and anxious about the shooting, Altena had the presence of mind to send several detailed reports immediately to SS superiors in Stuttgart and Berlin. At the same time, he made no statement to the local Saulgau authorities, which of course would have become part of public record. Altena claims to have reported promptly to Stuttgart and Berlin as a matter of protocol -- a highly dubious claim. More likely, he sought protection and praise from his superiors.

When asked the ultimate question -- why he, with pistol in hand, felt it necessary to shoot a knife-wielding person standing 4-5 meters (more than 15 feet) away, he simply replied: "Well, from a soldier’s point of view there is a moment of surprise."

His story -- practically every detail of it -- stood in direct contradiction to the testimony of other witnesses. For example, the three closest witnesses -- Ermler, Fuhrmann, and Hoelzle -- all testified that they were not in the immediate vicinity, having been forced away (Ermler) or sent off to look for other downed pilots (Fuhrmann & Hoelzle). Altena claimed, however, that Fuhrmann and Hoelzle were standing immediately behind him when the shooting took place. None of the witnesses testified that Nielsen had made any dangerous moves, and none among the now considerable crowd could remember seeing a weapon either before or after the shooting.

In a desperate search for witnesses to back his version of events, Altena implored a young Russian POW, who had witnessed the shooting, to testify on his behalf -- he refused. Altena also testified that he fired "once," maybe "twice." But even his own comrades-in-arms reported five or more shots at extended intervals. All witnesses agree that Altena was standing 4 to 5 meters from Nielsen, not four or five paces as Altena claimed. Even a knife-wielding Nielsen would have presented no threat to the pistol-packing Altena at this distance. Moreover, Altena’s self-depiction as a scared and concerned citizen-patient-soldier who, following the shooting, ordered an ambulance and, with special concern, personally loaded Nielsen’s boots into the ambulance, was shattered by Fuhrmann and Hoelzle, who testified that they left the scene with Altena shortly after the shooting, well before the ambulance arrived. In fact, it appears that Lt. Nielsen was picked up and moved to the ambulance by nurse Bullinger, her driver, and several concerned citizens well after Altena had left the scene.

This must have been a bitter and bewildering experience for Altena who, several days after the shooting, met with Fuhrmann, Hoelzle, and his housemaid, Frau Irene Dücker, to coordinate their stories. He correctly predicted that there would be an inquiry -- he knew he had committed a crime. What this SS major could not predict was that he would be betrayed by a nearly deaf, lock-eyed SA camp commander, a part-time SA man and local tailor, and his housemaid.

Death of an Airman

Dr. Max Stiegele was summoned to the hospital shortly after noon. There he found Lt. Nielsen lying on a stretcher, fully conscious but slipping away rapidly. Dr. Stiegele confirmed nurse Bullinger’s original diagnosis -- that the single stomach wound meant certain death -- and told Lt. Nielsen so. The doctor asked if there was anyone he should write. Nielsen responded that a letter should be sent to his family in Aberdeen, Washington. He was by this time too weak to clearly articulate the street address, but, the good man that he was, Dr. Stiegele wrote the letter anyway. He also asked to see a priest, and Dr. Stiegele saw to this request at once. Lt. Nielsen seemed comforted to be in the hands of the Sisters of the Catholic hospital, saying "O Sisters" to the nuns surrounding him.

The priest and Ms. Bullinger were at his side when the end came. Lt. Nielsen asked Ms. Bullinger to send his wedding ring to Artie, and after he was gone, she took the ring from his finger and placed it in a locked medicine chest. Oddly, Lt. Nielsen’s German certificate of death states "unmarried." On August 12, 1944, in a tiny cemetery following a service by Saulgau’s main priest, Father Müller, Lt. Theodore D. Nielsen was laid to rest. On the same day, his only child was born in Aberdeen.

Epilogue

As the Allied armies pushed eastward through the rural villages and forests of Schwabia, no trace of Lt. Nielsen was to be found. One year after notifying Artie that he was MIA, a letter from the army stated that Ted was "missing in action, presumed dead." A mass in his memory was held on December 22, 1945, in St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Aberdeen. Artie traveled shortly thereafter to Fort Lewis, where she received Ted’s Air Medal bearing an oak leaf cluster awarded posthumously for "exceptional service in aerial flight ... courage, coolness, and skill." The whereabouts of her husband were yet unknown.

For Major Friedrich Wilhelm Altena of the SA and SS, head of all resettlement programs for Aryans in the Third Reich and a personal acquaintance to Heinrich Himmler, the trip to War Criminal Prison Nr. 1 in Landsberg, fittingly the same prison that held Adolph Hitler in the late 1920s, was a bit like a modern Monopoly game: "Go to jail, go directly to jail." On January 22, 1948, final approval of the sentence was handed down by the War Crimes Review Board: life imprisonment. Altena had been lucky to escape the hangman’s noose. A review of his case in 1951 stated: "The Court apparently did not impose the death penalty because the accused was sick at the trial." It was obviously the view of the court that Altena would not last long anyway, a logical but misplaced assumption.

Sickly but determined, Altena continued to shuffle between military hospitals during his time at Landsberg. New political realities also intervened to help his plight. With Germany now central to the U.S. effort against the Soviet Union, Germany underwent rapid de-Nazification. The vast majority of Nazi war criminals, even those who had been sentenced to death, or as in Altena’s case, life imprisonment, were freed by the mid-1950s.

As early as October 1949, Altena appealed for release based on failing health. That motion was denied. Again in July 1950, Altena’s lawyer, Dr. Georg Froeschmann, submitted an appeal for his client’s release based on "advanced active tuberculosis" and, strangely, a change in testimony of Fuhrmann and Hoelzle. Fuhrmann, said the court of review, had tried to "soften" his testimony in a new statement, taken on August 15, 1949, in which he changed his testimony to say that "he was not in a position to see clearly what happened," though he did not change his testimony concerning the absence of a knife at the scene.

On July 25, 1949, in a post-trial statement, Hoelzle, in direct contradiction to his trial testimony, claimed that Lt. Nielsen had been "escaping and had not been captured yet" at the time of the shooting. In evidence introduced at the trial, however, Hoelzle stated that Nielsen had snapped to attention when the three approached him -- hardly an act of escape. Additionally, and in direct contradiction to his previous testimony, Hoelzle now said that he saw a blue dagger in Nielsen’s right trouser pocket, though he still could not corroborate that Nielsen had tried to attack Altena.

The review court, in a fit of legal anger, noted that someone "has gotten to" Hoelzle and "he is not reliable for any purpose. His statements, including those introduced at the trial, should probably all be entirely disregarded ..." A long list of friends and family now came to Altena’s aid. His new wife, Ruth, stated that he had been wrongly convicted and that his health warranted release. Gertrude Heye, Altena’s sister, said that her brother had acted in self-defense and should be released due to illness. Brother Fredy had several good reasons why Altena should be released: So that his brother could "undergo a cure for his sickness"; that he would personally see to it that Altena "will remain in his home town during his leave"; that his brother would soon die if he remained in prison; and, importantly, that Altena, the Godfather of Fredy’s son, should be released to witness the 8-year-old’s communion.

The final decision of the appeals court was unrelenting: Clemency denied. The court stated that Altena had acted under no stress on August 9, 1944, because the air raid warning had long passed by the time of the shooting. The court also noted that Altena did not rely on "superior orders" as a form of self-defense, making him solely responsible for his actions. Finally, the court noted that Altena quickly reported the killing to higher SS officials and chose to "ignore all of the local authorities," which "shows conclusively that he did know of the general policy of the then Nazi German Reich to kill all captured Allied flyers."

No one knows what happened to Friedrich Altena. His post-war life seems to have been as unremarkable as the man himself. The last prisoner to walk out of Landsberg Prison in 1958 was not Altena. Nominally, Altena remained a prisoner at Landsberg, though he was seldom there. From January through June 1954, Altena was on "medical parole" in Gauting, Germany, site of the State Hospital for TB. He was returned to prison on June 30, 1954, after his health improved and funds ran out for his treatment. In September of the same year Altena was granted a second medical leave at the cure in Wilershofen-Weiden.

Sick or no, model prisoner that he may have been, the American military courts stuck firm: no clemency as late as 1955. Reflecting the anger at Altena’s act, and possibly for the fact that he managed to live so long and stay out of prison in spas most of the time, the clemency officer wrote bitterly in the mid 1950s: "The findings of guilty are clearly warranted by the evidence, and the findings of the court on the issue of self-defense are final and conclusive ... The cruelty of Altena and his lack of mercy for the captured and helpless airman demonstrate a criminal character completely devoid of social duty and unworthy of any consideration of clemency."

It is an interesting and ironic side-bar that Altena, a man who had narrowly escaped capital punishment and was now fighting for release based on his medical condition, once told his housemaid that he intended to kill himself when Germany lost the war. When asked at the trial he simply replied, "At first I intended to do that, but I refrained from it." Even here he changed his story.

Joseph Halow, American court reporter at the Dachau Trials, claimed in a 1996 letter to Mr. Hans Behrend of Sigmaringen, Germany, that it was "highly unlikely that Mr. Altena had to stay longer than 10 years in prison" because the U.S.A "quickly developed a new opinion." Halow stated that "as soon as he was released, the files would not contain any more information about him or his future life."

It is an odd and sad twist of irony that Halow’s name emerges from Lt. Nielsen’s file in Sigmaringen, Germany. Halow, in his very controversial book Innocent At Dachau, published by Noontide Press, itself notable for publishing "hard-to-find politically incorrect books," claims that most of the defendants at Dachau were innocent and unjustly sentenced. He is regarded by some as a "Holocaust denier" in Germany, where his book is banned from the shelves to this day.

War has a way of bringing out the best and worst in people. War could not corrupt the kind heart of Dr. Max Stiegele. True to his death-bed promise, Dr. Stiegele wrote that letter, which arrived in the Aberdeen mayor’s office in June 1946, nearly two years after Lt. Nielsen’s death. Penned on the envelope was a request to forward the letter to "Mrs. Neilson," mother of "pilot Theodore Neilson."

Since Lt. Nielsen’s mother passed away in 1939, followed by his father in 1941, the letter found its way to his wife and sister. Now the truth of that fateful day was finally revealed. Dr. Stiegele wrote about the last day of Lt. Nielsen’s life, and he assured the family that a priest had been on hand at Ted’s demise. The wedding ring, so carefully cared for by nurse Bullinger, never found its way back to home. It was given to a French Occupation official, along with Nielsen’s other personal possessions, shortly after the war. As if by a cruel intervention of irony and fate, Mrs. Artie Nielsen lost her wedding ring shortly after the war.

Lt. Theodore D. Nielsen’s body was exhumed from the Saulgau cemetery after the war and moved to the beautiful and pristine Lorraine American Cemetery in St. Avold, France. There, at Plot B, Row 26, Grave 56 -- nine hours and thousands of miles away from Aberdeen -- rests a young husband; a young father; a young printer; a young trombonist -- and a brave young pilot.

Nielsen's wife married an Aberdeen man and she died in 1996. Nielsen's daughter lives privately in Washington state.

In 2005, the citizens of Bad Saulgau dedicated a monument and memorial tablet near the location where Lt. Nielsen parachuted. The inscription is in German and translates as follows

Theodore D. Nielsen 1922-1944

American pilot Lt. Theodore D. Nielsen was fatally shot at this site on 9 August, 1944. The 22 year-old pilot parachuted to safety when his plane was struck by flak. He surrendered to an SS officer who, rather than take him prisoner, killed the unarmed pilot in cold blood.

The perpetrator was given a life sentence in 1947, from whence he was released after 10 years.

Theodore D. Nielsen left behind a wife and daughter.