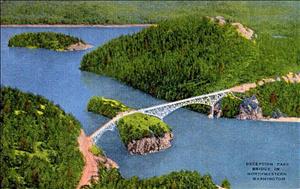

On July 31, 1935, the Deception Pass and Canoe Pass bridges are dedicated. Deception Pass, located at the northern end of Puget Sound, is a treacherous, narrow channel with turbulent waters, rapid tidal action, and rocky outcrops.It separates the high bluffs of Whidbey Island from those of Fidalgo Island. A rocky islet, Pass Island, rises in the mouth of the pass and divides it into two channels. Deception Pass Bridge connects Whidbey Island to Pass Island, and Canoe Pass Bridge connects Pass Island to Fidalgo Island. The bridges rise from steep bluffs high above the sea and present a breathtaking sight. The steel cantilever Deception Pass Bridge and the steel arch Canoe Pass Bridge were financed by New Deal state and federal agencies. Five thousand people attend the dedication

Spanish explorers originally charted the waters dividing Whidbey and Fidalgo islands in 1791. In 1792 the English explorer George Vancouver named Deception Pass following the discovery by his navigator Joseph Whidbey that what they thought was a peninsula was an island (Whidbey Island) and what they thought was a bay was the deep channel dividing the two islands. The pass, posing as a bay, had deceived them, thus the name.

The Ferry-Bridge Debate

By the turn of the twentieth century, settlers were taking ferryboats between Whidbey and Fidalgo islands and to the mainland. To some, a bridge seemed like a good idea. By 1907, local mariner and legislator Captain George Morse was campaigning for a bridge. Morse secured from the state legislature $20,000 to build one, and he unveiled models of his through-truss bridge at the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition. His dream of a Deception Pass bridge evaporated when the legislature reappropriated the money.

Later, ferry interests, particularly the gutsy Berte Olson (1882-1959), opposed bridges and fought bridge advocates. Olson was a Norwegian-born ferry operator who with her husband ran ferries at Deception Pass and in Hood Canal. She was a force to contend with. The legislature unanimously passed a bill for a Deception Pass bridge in 1929, but she prevailed upon Governor Roland Hartley to veto it. The override campaign failed.

In 1930 the Deception Pass Bridge Association re-formed and in 1933 bridge legislation again passed. By this time Clarence Martin was governor and he did not veto the bridge.

This was at the height of the Great Depression and Franklin D. Roosevelt’s economic recovery program -- specifically the New Deal Washington Emergency Relief Administration along with the federal Public Works Administration and the counties -- paid for construction. The bridge engineer was O. R. Elwell. The bridge fabricator was Puget Construction Co. of Seattle and the steel fabricator was Wallace Bridge and Structural Steel Co. of Seattle.

Building Bridges

The cantilevered Deception Pass Bridge and the arched Canoe Pass Bridge were built in tandem. First, workers excavated solid rock for the pier footings. They used jackhammers and dynamite to break up 3,300 yards of rock. Then they poured the concrete for the pier footings.

The approach spans rested on reinforced-concrete columns, and the main spans rested on U-shaped bents (supports lying crosswise). The contractor erected two concrete mixing plants, one on the Whidbey Island side of Deception Pass for the south cantilever piers (with water piped from Cranberry Lake) and the other on the Fidalgo Island side of Canoe Pass for the north arch piers (with water piped from Pass Lake). A cableway (which they called the high line) was built from Fidalgo Island to Pass Island to transport cement and crushed rock (the ingredients of concrete) to build the south arch piers and the north cantilever piers

After workers completed the Canoe Pass arch bridge, they built a railroad track to run across that bridge to transport supplies to Pass Island and the north side of the Deception Pass Bridge.

This bridge had two cantilever spans -- arm-like structures sticking out from the support columns on each end. The two cantilever spans were then to support a center span. Unfortunately, when it came time for the crane operator to lower the center span into place, the span was three inches too long. It was a hot summer day, and heat had caused the steel to expand. The clever engineer, Paul Jarvis, founder of Puget Construction Company, pulled out his pad and pencil and figured that when the temperature dropped 30 degrees the steel would shrink by three inches. The crew returned the next morning before dawn, at which time it was 30 degrees colder. Working by floodlight, they lowered the center span into place, and it fit perfectly.

Dedication Day

During the next two Sundays, some 3,000 to 5,000 vehicles arrived and crossed the bridges. Over the next years, Whidbey Island's population burgeoned. During World War II, the U. S. Navy built an air station on the island and this has continued to employ many people.

The Deception Pass Bridge and the Canoe Pass Bridge have helped to make the Pass a major tourist destination in the state of Washington.