On December 28, 1857, the Cape Flattery Lighthouse on Tatoosh Island begins operation. Built between 1856 and 1857 on a 20-acre bean-shaped rock at the northwestern-most point of the continental United States, Cape Flattery Lighthouse is the first of an evolving series of navigation aids on the island that will assist mariners in entering the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Fog, Currents, Tides

The 12-mile-wide Strait of San Juan de Fuca leads to the protected waters of Puget Sound and its resource-rich waters and shores. But fog, strong currents, and treacherous tides at the strait’s entrance can make approaching it hazardous. Fog sometimes totally obscures the entrance and at other times hangs over it in isolated spots. Strong currents can carry unwary or disabled ships north toward the dangerous western shores of Vancouver Island. Rip tides, created by the return flow of waves and wind-driven water, add to the maelstrom as do wind gusts that can exceed 100 miles-per-hour. English explorer Captain James Cook (1728-1779) wrote in 1778 of the area: "Beetling cliffs, ragged reefs, and huge masses of rock cut by the waves abound on every side."

Although the area’s Native Americans, explorers such as Cook, and fur traders navigated the strait prior to the nineteenth century, by the mid-1800s increased maritime traffic led to demands for navigation aids that would lessen its dangers. In 1850, the U.S. Coast Survey investigated the Oregon and Washington coastlines. Its investigators recommended placing a lighthouse on Tatoosh Island, off Cape Flattery on the southern side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Placing a light there would, the surveyors said, allow vessels to enter the strait at night. It would also assist them in reaching safe harbor at Neah Bay, about four miles inside the entrance. Congress adopted this and other advice of the Survey.

A Green Island

Tatoosh, a 20-acre island lying one-half mile off the cape, is actually an extension of that promontory, connected to it by submarine rock ledges. Rainfall on the rock averages 100 inches annually. Treeless, but carpeted in green, the island rises abruptly from the sea to a height of about 100 feet. It has only three areas suitable for landing boats, all hazardous and often impossible to use because of prevailing winds and tides.

The Makah Indians used Tatoosh as a summer village site, with several hundred tribal members living there from March through August. They ventured out from its shores to hunt whales and other sea mammals, and to take halibut and other fish. James G. Swan (1818-1900), a nineteenth century ethnographer who lived among the Makah for three years, recorded the Makah's name for the island as Chadi.

The island has had various other names. Spanish explorers called it Isla de Punto de Martinez for Juan Jose Martinez, second-in-command and navigator on Juan Perez’s ship Santiago, which traversed this coast in 1774. English fur trader Charles Duncan labeled it Green Island in 1788. However, the name of the Makah chief Tatoosh, as understood by later English explorers, became customary usage for the rocky feature. Swan speculated that they named the island for Tatoochatticus, a northern (Vancouver Island) potentate "who, with Maquilla, and Callicum, two other powerful northern chiefs, held sway over the country in the region of the straits of Fuca" (Swan, 1971).

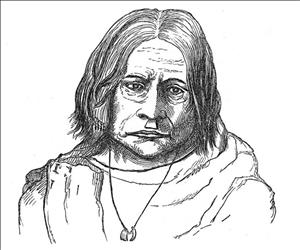

English fur trader John Meares (1756?-1809) in the Felice arrived at the island on June 30, 1788, and met the Chief Tatoosh of that era. "Canoes came out from the island with twenty or thirty men in each who looked very savage, with painted faces and sea otter cloaks. They were armed with bows and arrows with barbed bone points and large spears pointed with mussel shell. The group included the chief, Tatooche, whose face was painted black and glittered with sand" (Meares, 1790). Meares, who had named the entrance to Puget Sound after its original discoverer, John or Juan de Fuca, recorded the island as Tatooche or Tatoosh Island on his charts.

A Disputed Island

Nineteenth century American settlers believed that the Makah gave up their rights to Tatoosh Island and all of their other traditional lands except for a small reservation at Neah Bay in 1855 return for a $30,000 payment by the federal government. The Makah apparently did not see it that way. This may have been because in their treaty with the government, negotiated by Washington Governor Isaac Stevens in 1855, they retained rights to traditional fishing and hunting grounds.

Lighthouse construction began sometime in the next two years although Congress did not establish a lighthouse reservation on the island until June 8, 1866. The Makah resented the building and interfered with the work, so the builders, armed with 20 muskets, built a blockhouse before starting on the lighthouse.

Lighting the Sea

Contractors completed construction of the lighthouse on Tatoosh Island, known as the Cape Flattery Light, in late 1857. It consisted of a Cape Cod-style sandstone dwelling with two-foot-thick walls. Kitchen, parlor, and dining room were on the first floor. Four sleeping rooms were in the half-story above. A 65-foot brick lighthouse tower rose from the center of the dwelling. Because there was no fresh water on the island, the structure’s gutters collected rainwater and drained it to a cistern.

The lighthouse occupied the highest point on the island, 90 yards from its extreme western point, 25 yards from the cliffs, and 97 feet above the sea. The iron lantern room at the top of the tower held the light. That light, a 10.5-foot-high first-order Fresnel lens built in Paris in 1854 by Louis Sautter & Company, showed a fixed white light visible at a distance of 20 miles. Cape Flattery first displayed its light on December 28, 1857. Winter storms frequently threw spray high enough above the 80-90-foot cliffs to coat the windows of the lighthouse with salt. Nearby, a fog bell sounded a warning when necessary.

First Keepers

George Garrish was Cape Flattery Light’s first head keeper. He moved into the new lighthouse with three assistants. He and two assistants quit after two months, citing as their reasons hard work, isolated location, and danger from Indians. Franklin Tucker and two new assistants replaced them. The new arrivals left after three months, blaming low pay and fear of the Makah.

Little help was available to the keepers. In 1858, Isaac Smith, Light-House Agent for Washington Territory, wrote to his counterpart Indian Agent M. T. Simons, reporting that the Indians could not be kept out of the lighthouse, had broken into the light keepers’ storehouse, had struck the keeper, and threatened to kill him. Simons replied that he had questioned the Indians, who had nothing to say. He said that should Smith arrest any Indians, he would confine them, but advised the keeper not to attempt any arrests "unless your force is sufficient to make it certain" (Simons, May 28, 1858).

In 1860, William W. Winsor arrived at Tatoosh as the third head keeper. Shortly thereafter, a visitor described trying living conditions at the lighthouse. Rain seeped in under the roof’s shingles, wind drove chimney smoke back into the dwelling, and moss grew on interior walls. This state of affairs lasted until 1875, when authorities repaired the old keepers’ quarters and also built a new, detached living structure.

Relations with the Indians had apparently improved by 1885. At that time Captain Henry Ayres, a Union Army Civil War veteran hired as an assistant keeper, arrived with his wife and young daughter, Jesse. Prior to this, keepers’ families had been banned due to fears of Indian trouble.

Lighthouse Technology

Technological changes arrived as the years passed. In 1872, a $10,000 steam-driven foghorn replaced the original fog bell. In 1883, the Department of Agriculture established a weather station that would operate on the island until 1966, with a break in service only between 1898 and 1902. In October 1887, the keepers inserted a red panel in the Fresnel lens to cover the positions of Duncan and Duntze rocks, about a mile from the lighthouse, so that in those areas only a red ray was visible.

Other technological improvements followed. Keepers’ duties were lightened, literally, when they no longer had to carry buckets of oil to the lighthouse lamp. Tubing from oil storage tanks below fed oil to the lamp. Plungers positioned above the oil forced it through the tubes as needed. Nevertheless, one keeper had to remain at the top of the lighthouse throughout each night to assure that the lamp burned properly.

By 1883, a telegraph line described as the longest hung cable in the world, stretched from the island to the mainland and connected Tatoosh with Neah Bay. When shipwrecks had to be reported it connected the lighthouse with a life saving station established at Neah Bay. The telegraph helped to prevent shipwrecks by providing outbound mariners with reports on conditions outside the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Daily reports went out and relayed via Port Angeles to Port Townsend until June 1898. In 1886, the Post Office Department designated Tatoosh a fourth-class post office and appointed Alexander Sampson as first postmaster. In 1902, the Weather Bureau reactivated its Tatoosh station, this time establishing buildings of its own with full time officials on the island.

Special Deliveries

Mail arrived at the island weekly by Makah canoe. When landings were impossible, the canoeist lobbed the mail to a keeper teetering at water’s edge. In addition to mail, "firewood, people, cows, and even a piano were loaded at Neah Bay and paddled to the island in dugout canoes" (Nelson, 1998). Regular deliveries of supplies arrived once or twice a year on lighthouse tenders such as the Manzanita or Columbine. Derricks lifted supplies in boxes from ship to the top of the island. This is how passengers disembarked as well.

John Merrill Cowan, promoted from Assistant Keeper at Coquille Lighthouse, Bandon, Oregon, to Head Keeper at Tatoosh, arrived on the island with his family on May 16, 1900. He would remain until retiring in 1932. Stoic, he would recover from seeing a son drown when his boat overturned while coming back from an excursion to the mainland. Imaginative, he would build his children a Christmas tree from salvaged boards and branches cut from bushes on the treeless island’s cliffs. In February of 1911, storm winds bowled Cowan over and blew him 300 feet. He was fortunate not to be injured or even drowned. The same tempest blew a bull off the island and into the sea, from which the animal emerged angry and alive.

In 1902, the same year the Weather Bureau arrived back on the island, a government ship wireless (radio) station began operating on the island. The Puget Sound Tug Boat Company operated the facility as a contractor. Service was open to the public for sending and receiving, but irregular. After a 1902 Christmas Day gale blew down the telegraph line, The [Port Townsend] Morning Leader said that the government would never be sure of its Tatoosh communications until it instituted better radio service. In 1904, Tatoosh also became a junction point for an undersea telegraph cable from Alaska to Seattle.

Electricity was necessary to the radio station and presumably provided by powerful generators. They must also have supplied the lighthouse with power, increasing the intensity of the beacon. The Lighthouse Service reported a white light of 13,000 candlepower and a red light of 4,000 candlepower.

By 1908, better service prevailed. Naval radio station NPD was operating from Tatoosh Island with 15 kilowatts of power on a wave length of 600 meters. Its low-powered signals could transmit and receive ship-to-shore traffic and distances of up to 1,000 miles. NPD relayed messages with more distant destinations to high-powered naval facilities in Puget Sound for retransmission. The radio service also enabled reports from the island of maritime casualties, derelicts, overdue vessels, and vessel movements.

Congress reinforced the island’s naval presence in 1912 by specifying that at key strategic points such as Key West, Florida, San Juan, Puerto Rico, and North Head and Tatoosh Island, Washington, and San Diego, California, commercial messages would be handled entirely by naval stations. After radio direction-finding techniques were developed during World War I (1914-1918), Tatoosh Island facilities added this capability and also began to broadcast a radio compass beacon on 375 kilocycles.

In 1914, an oscillating light that appeared for intervals of four, four, and 16 seconds with two seconds of eclipse in between, repeated every 30 seconds, replaced Cape Flattery Lighthouse’s fixed beacon. The steam foghorn emitted blasts of eight seconds duration every minute in thick weather, a signal later changed to two unequal blasts per minute. About 1932, however, the Lighthouse Service replaced Cape Flattery’s towering first-order Fresnel lens with a much smaller fourth-order lens. The larger lens ended up in a crate on Seattle’s waterfront and was broken up in the backyard of a local glass dealer.

Twelve families lived on Tatoosh Island in 1939. In addition to serving coastal and transoceanic shipping, the island’s lighthouse and other navigation aids also assisted a growing fleet of small fishing vessels. During October 1939, the lighthouse keeper counted 436 trolling boats within five miles of the island.

The War Years and Beyond

World War II (1941-1945) brought the next major changes to Tatoosh Island. More naval communications ratings arrived. They set up an intercept station that searched the airwaves for radio signals of the Japanese Army and Navy. The focus of the island’s radio direction-finding effort shifted from assisting navigators to tracking enemy ships.

Marines arrived to guard the naval station and the lighthouse.

Although Tatoosh’s naval radio station closed after World War II, the war also brought to the island another navigation aid, LORAN (LOng RAnge Navigation), which continued to operate. Developed during the war to aid aerial navigation, the service was quickly adapted to assist mariners. Loran receivers, mounted on most ships and on many smaller craft in the postwar years, measure the time difference in receipt of synchronized electromagnetic wave transmissions from two or more transmitting stations, providing yet another means of fixing a vessel’s position.

In the late twentieth century, Tatoosh Island retained its nineteenth-century lighthouse, its early twentieth-century radio beacon, and its mid-twentieth-century LORAN transmitter. By 1977 all, including the lighthouse, were automated, so that no keepers had to live on the island. In 1996, a small solar-powered optic replaced the fourth-order Fresnel lens installed in 1932, decreasing further the need for maintenance visits.