On January 15, 1931, a dance marathon closes at the Playland Ballroom on Bitter Lake, north of Seattle, after 1,545 hours (70 days, or more than two months). Dance marathons were human endurance contests in which couples dance or shuffle almost non-stop for many hundreds of hours, competing for prize money.

Dance marathons, also called walkathons, were popular if not fully respectable entertainment during the late 1920s and 1930s. The fad began as one of many giddy, jazz-age diversions such as flagpole sitting, goldfish swallowing, and six-day bicycle races. After the 1929 stock market crash, dance marathons lingered on the fringes of polite society.

Most, if not all, winning contestants were hardened professionals who worked the dance marathon circuit. The handful of men who promoted dance marathons around the country often had their own stable of regular contestants. Known as "horses" within the business for their ability to endure week after week on their feet, these professional dance marathoners also usually had personas they adopted (such as the Sweetheart Couple, the Tough Guy, etc) in order to milk sympathy from the audience. Professionals also usually had songs or vaudeville-style specialty numbers with which they entertained the crowd. These numbers broke up the monotony of watching the contestants circle around and around, and enriched the contestants when audience members showered them with coins. Amateur contestants were encouraged to enter, but they rarely lasted long.

Dance marathon contestants were required to remain in motion 24 hours per day, with 15 minutes rest time per hour. Because the Playland marathon lasted so many weeks it is possible that promoter Al Painter engaged in the common marathon deception of giving favored couples extra rest time during the wee hours of the night when crowds were slim. Such couples’ absence from the floor was explained away with ruses such as that they were receiving medical attention or personal grooming.

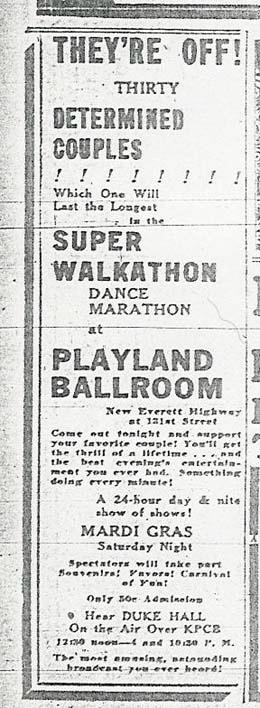

The Ballroom at Playland boasted a 9,600-square-foot hardwood dance floor. It opened, along with the amusement park itself, on May 24, 1930. The dance marathon began a few months later on November 6, 1930, probably as a publicity attempt. For the purpose of the dance marathon, the Ballroom/Dance Pavilion was converted into a stadium with 3,000 spectator seats. “Duke Hall will act as master of ceremonies and he will stage special entertainment features. There is a grand prize of $1000. Physicians and two trained nurses will be in constant attendance” (The Seattle Star, November 5, 1930).

Duke Hall was touted to be “the Al Jolson of the radio mike.” Radio listeners were urged to tune in to KPCB from 10 to 10:30 pm on November 6 to listen to “a vivid picture of the thrills, humor and pathos of the first hour of this grueling contest … How Long Can They Go?” (The Seattle Star, November 6, 1930). KPCB broadcast bulletins from the Playland marathon daily at noon, 4:40 p.m., and 10:00 p.m.

Leo F. Smith, co-owner of Playland in its very early days, was president of the Washington Amusement Company. He had built other amusement parks at Columbia Beach and Jantzen Beach in Portland. Promoter Al Painter had previously mounted marathons in these locations.

Dance marathons attracted large audiences. Anyone who could pay the 50-cent admission price was welcome to stay as long as they liked. Some people made the journey to Playland daily. The Seattle-Everett Interurban stopped at the edge of the park, and some Seattleites came by car. The audience most likely came from as far north as Everett. Radio broadcasts generated publicity and kept awareness of the contest high, but Painter and Smith faced a substantial hurdle in mounting a dance marathon close to Seattle. A 1928 dance marathon at the Seattle Armory had ended disastrously with the suicide attempt of a contestant. The 1928 marathon and its aftermath had received enormous coverage in the Seattle newspapers. As a direct result of this fiasco, the Seattle City Council passed Ordinance 55985 outlawing the contests.

Playland Ballroom, located on Greenwood Avenue at 131st Street, stood 46 blocks outside the Seattle city limits at the time. The Playland marathon was thus technically legal but received no coverage in The Seattle Times or the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Coverage in The Seattle Star was limited to four very short articles and seven display advertisements during the entire two-and-a-half month run.

Nevertheless, apparently the KPCB broadcasts generated sufficient crowds. During the dark winter of 1930-31 (early in the Great Depression), the mood of both the country and the Pacific Northwest was grim. Dance marathons, if shoddy spectacle, were at least temporarily diverting.

On November 15, 1930, advertisements exhorted fans to attend a “Mammoth Midnight Frolic Tonite. Come out and make whoopee into the wee hours of the morning. Noise-Makers, Souvenirs, Whoopee." The main event of the evening was to be a marathon wedding. "Pretty Patricia Fagen and Handsome Leonard Buckley, Couple No. 2 -- sweetheart couple of the contest -- will be married on the contest floor in a Grand Public Wedding” (The Seattle Star, November 15, 1930).

Public weddings were a staple of the dance marathons. The marathons were largely performative (i.e. staged), although considerable endurance was required to survive the grueling hours. Public weddings were a common form of marathon pageant. Fellow contestants were costumed as attendants, audience members brought wedding gifts, and the happy couple usually got an extra stipend from the promoter. Attendance ran high for marathon weddings, which were sometimes real marriages performed by clergy and sometimes simply acted out (although the audience was supposed to think they were real). Such marriages were almost always annulled after the marathon ended -- at the promoter’s expense. Some professional contestants were married again and again in various dance marathons.

Marathon fans who couldn’t make the ceremony could “telephone HEmick-1734 for last-minute marathon reports” (The Seattle Star, November 15, 1930).

On November 20, 1930, with two more couples down, audiences were given another standard dance marathon treat: “Training quarters, nurses, trainers and beds for the girl contestants brought to the center of the floor for rest periods on Friday night only. See how these determined athletes carry on their battle for fortune and fame -- Eight tired but determined couples have passed the 300 hour mark in their struggle for the $1000 grand prize and a world’s record” (The Seattle Star, November 20, 1930). This so-called cot night gave audiences a glimpse of what the contestants did in their brief rest periods -- sprawl catatonically, for the most part.

By December 30, only three couples remained. These six contestants ground on until the contest finally closed on January 15, 1931. Promoter Al Painter was not known for the grueling sprints and zombie treadmills (endless laps of the arena) featured in many other marathons. Perhaps the contest ended with a draw -- top finishers sometimes privately arranged to split the prize money evenly in order to end a contest. Possibly audience attendance had also fallen.

The top three finishing teams (identified on a period commemorative photo only as Porky, Bella, Mickey, Leila, Ducky, and Peggy) had lasted for 1,545 hours. During the marathon’s course the Seattle papers held almost daily news of despondent citizens jumping out windows and turning on the gas to end their lives. Within a few months the Washington Amusement Company would fail. Al Painter continued promoting dance marathons throughout the Pacific Northwest. The events persisted throughout Washington until a statewide ban was enacted in 1937.

Sometime prior to 1937 the dance hall at Playland was converted into a roller skating rink that boasted a real pipe organ. Later it housed arcade games and a casino. The facility was closed along with the rest of Playland in the autumn of 1961.