John Harvey was an English-born settler who arrived in the Oregon Territory and Alki Point in March 1852, four months after the Denny Party arrived. Harvey staked a claim on Lake Washington, experienced the treaty wars of 1855-1856, and later moved to Snohomish County where he became a significant pioneer in the county. This account of his life was written in 1984 by his grandson, Eldon Harvey, and by Eldon's daughter, Donna Harvey. The "I" in the account is Eldon Harvey.

John Harvey

John Harvey was born near Modbury, in Devonshire County, England, 14 miles from Plymouth, on March 9, 1828. Harvey had a boyhood dream of going to America. After listening to stories of sailors, America was seen as a vast expanse of fertile farmland available to everyone, where you could have all the crops and animals you could raise.

Harvey was about 21 years old in 1849, when he found a ship sailing for San Francisco from England. Since he had no money for passage, he signed on as a sailor. It took approximately two months to make the trip down around Cape Horn and up the coast to San Francisco.

He told the story that somewhere along the trip some sailors went ashore to get water and food. Coconuts began falling on them while they were working. They could not understand what was happening until they looked up in the trees, and saw that the monkeys were picking coconuts and throwing them at the sailors.

The ship arrived in San Francisco in 1849. At that time, there was so much excitement about the discovery of gold in California that many of the sailors were refusing to return to the ships. Such refusal was making it difficult and sometimes impossible for ships to return to their homelands. Because of this, a law was passed in England making such refusal punishable by death. This forced Harvey to change his plans. He returned to his ship. As the ship was leaving the harbor and departing for England, Harvey “jumped ship” and somehow got back to shore.

Now, safely in America, but with absolutely nothing (no money, no clothes, and no belongings), Harvey found work in various capacities in the gold fields until 1852. (According to the 1850 United States Federal Census, Harvey was mining in the area of the South Fork of the American River in El Dorado County, California.)

Harvey arrived in the Oregon Territory on March 17, 1852, possibly on the brig John Davis landing at Alki Point, Seattle, Washington. This was four months after the families of Arthur Denny, John N. Low, C. D. Boren, Wm. N. Bell, along with Charles Terry and his brother, Lee, landed at Alki. These men and their families were the pioneers in the beginning of Seattle. Alki Point was said to be the first American settlement on Puget Sound.

For a short time, Harvey, a single man, worked for J. N. Low, who was logging at Alki. After that, he worked in getting out logs for pilings and hewn timber on the bay side, for which he had a large contract at Alki. (Pronounced Al-ke by the early pioneers, which means “by and by” in Chinook Indian language.) The pilings and timber were for the San Francisco market and occasionally there was a cargo for the Sandwich Islands. Vessels in the lumber trade carried a stock of general merchandise from which the settlers obtained their supplies.

On April 10, 1852, Harvey commenced his settlement on a Land Donation Claim of 160 acres along the shore of Lake Washington that included the Isthmus and Southern part of Seward Park. At that time, he was 24 years old. Harvey must have met his friend, E. A. Clark, who also was a miner in El Dorado County, California during the gold rush.

In the Prologue to his novel General Claxton, Cornelius Hanford (1849-1926), who was a son of Seattle pioneers Edward Hanford and Abigail (Holgate) Hanford, states that Clark and Harvey were passengers on the brig John Davis, commanded by Captain George Plummer. The brig was sailing on a general trading voyage to obtain a cargo of Puget Sound Lumber. Clark acquired a claim adjacent to Harvey's on Lake Washington. (The only source of the information that Harvey and Clark sailed on the brig John Davis is in the Prologue to Cornelius Hanford's novel.)

The site on Brighton Beach that they chose for their buildings was probably a prairie that had been at least partially cleared previously for the construction of two longhouses. This area was known to the Duwamish Indians as xaxao’Ltc (hah-HAO-hlch), the “forbidden” or “taboo place,” because a supernatural being dwelled there and “caused the babling of ripples on the water.” The Duwamish typically cleared a few acres around longhouses and maintained prairies by periodic burning. The site was later referred to as Clark’s Prairie. According to an article by Mabel Abbott, Harvey and Clark built a house across the common boundary of their claims “so each could live on his own land and yet have company in the lonely forest.”

After the opening of Yesler’s sawmill, in the spring of 1853, Harvey began working to supply logs for the mill. He was employed in clearing the claims of Edward Hanford and John Holgate on Elliott Bay. When the Indian War started in the fall of 1855, the logging operations stopped.

The white settlers at that time desired wives to help with chores and to begin families; so some of the new settlers married Indian women. It was also wise to form alliances with tribal members and their extended families. Some people considered the Indians to be violent and cruel, but we understand now that they felt threatened, and knew their land was being destroyed and taken from them. The story passed down through the Harvey family is that John Harvey may have had an Indian wife at that time.

Born in the 1780s, Chief Seattle led the Suquamish and Duwamish tribes as whites settled in the area. He and 80 other Indian leaders ceded Puget Sound territories to the United States in the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott. Some of the Indians were not exactly happy with this treaty.

The Indian wives heard through their Indian families that the Yakima and Wenatchee tribes were planning an unexpected attack on the white settlers. When the wives heard this news, they alerted their white settler husbands and all of the settlers retreated to the blockhouse. There were several blockhouses -- one had been built on a bluff at the tide water just before the outbreak of the Indian War in 1855. (That area is where Cherry Street and 1st Avenue are located today.) I [Eldon Harvey] think there were a total of three blockhouses strategically located for protection of the settlers. Since the homesteaders left in such a rush, they were unable to bring any supplies except their guns and the clothes on their back.

The following story was told by John Harvey to his son, Noble, and then to his son, Eldon. Soon relations with the Indians and the settlers became hostile and that led to the battle in Seattle. Harvey had joined the Volunteers for six months. The Volunteers were a group of men that banded together to protect the white settlers. Harvey was forced to leave his cabin and belongings and seek protection at the blockhouse. The settlers were getting hungry, and they could see the inevitable; they were either going to be killed or starve to death. One of the men managed to slip through the blockade and make his way to Bellingham, where he persuaded the captain and crew of a fur-trading vessel to sail to Seattle to help the settlers.

The ship sailed close enough to shore to be able to fire directly into the Indian camp. The ship carried a short cannon that fired a four-inch iron ball. The ship’s cannon was fired at the attacking Indians. After they dug the iron ball out of the ground, the Indians decided that if there was a man aboard the ship, who could fire a gun of that size, he must be the devil, so the siege was soon ended. The gun that Mr. Harvey carried into the blockhouse was made by Eli Whitney and was among one of the relics saved from that historic period. It is still owned by the Harvey Family.

Published history of the Battle of Seattle is different from the story passed down through four generations of the Harvey family. The Indian War began east of the Cascade Mountains during the summer of 1855 while Governor Stevens was still busily making treaties. (Governor Stevens was appointed territorial governor in 1853.) There were several incidents, and when things were beginning to look serious, the citizens diverted a cargo of square timbers for shipment to California and used it to build a blockhouse. While it was being built the town enjoyed its first visit from the United States Navy. The sloop-of-war Decatur had come across from Honolulu under orders to “cruise the coast of Oregon and California for protection of the settlers.” The skipper had fortunately allowed enough leeway in his orders to include Puget Sound in his cruise. Seattle was attacked by the Indians on January 26, 1856, and the Decatur which had been around all winter, almost failed to get into the show.

A few days later, the Battle of Seattle began working toward a climax. Into Elliott Bay steamed the survey ship Active with Governor Stevens aboard. He was back from the Blackfoot treaties and he still wasn’t wasting any time. He tried to talk the skipper of the Decatur into abandoning Seattle and going with him on a cruise to Bellingham Bay. He returned to the Active in a rage and departed without further delay. While the Active was still in sight in the bay, friendly Indians began coming into town looking for protection. They reported that large bands of hostiles had already crossed Lake Washington and were taking up position for an attack on the town.

Harvey may have gone to the Duwamish blockhouse, which was probably closest to Harvey and Clark’s claims. They may have gotten all their information about the Decatur’s role in the war secondhand considerably after the fact. This might have contributed to the differences between the family story of the war and published accounts. It is hard to pick truth from fiction on how the Indians warned the white settlers of the pending attack.

On the Final Proof of Land Donation, it stated that Harvey resided on the property adjacent to Lake Washington from April 10, 1852, until April 10, 1856, “except for the period of about six months from October, 1855 to July, 1856, when on account of Indian hostility, it was unsafe to remain on his claim. During that time, he was engaged as a Volunteer to suppress Indian hostilities.” When the Indian War started in 1855, businesses were dissolved and the men went into Volunteer service for six months.

Harvey’s claim along Lake Washington was in the vicinity of Seward Park. In fact, the claim included the Southern part of Seward Park including the Isthmus. It is believed the Harvey and Clark’s buildings were located in the area of Lakeshore Drive South and South Eddy Streets. Brandon Street was the boundary on the north side of Harvey’s claim and 51st Avenue was the western boundary. Graham Hill was also part of the claim.

After the siege, Mr. Harvey returned to his claim, found that all of his crops had been destroyed, the buildings burned, fences gone, and his cattle slain and eaten. Harvey filed a claim for losses of buildings on his claim after the Indian war in the amount of $2,150. The claim was filed with the third auditor of the treasury at Washington and never paid. No compensation was ever received by any of the settlers who filed claims.

Harvey did not return to live on his claim, and worked in lumber camps and sawmills until 1859. On December 28, 1858, E. A. Clark sold his claim to David Graham, and a week later on January 6, 1859, Harvey did the same. Harvey sold his claim for $2,000.

Since he had decided he did not want to stay on the original claim any longer, he and a fellow Englishman, Sam H. Howe, who had also lost everything in the battle, decided to build a scow on Whidbey Island. They loaded the scow with the idea of setting up a store at mouth of the Snohomish River. The scow hauled a head of oxen, some potatoes, and supplies. They depended on the tides to cross the Sound.

When they reached the Snohomish River, they found a lot of mud flats, and decided to turn and go up the Snohomish River. They got up to about where the town of Lowell (now part of Everett) is located, and the water became a bit too deep to move the boat along with the poles, so they drifted up with the tide. When the tide went out, they would tie up the boat and go ashore, stay the night and wait for the tide to come back in. They expected to use poles in pushing the scow upstream. But they found the current too strong for this and were forced to pull the scow up stream by tying a rope to a tree and pulling the scow up to that point, and after securing the boat, carried the rope farther up the river, fastening it to another tree. They found this a most laborious undertaking, and after working in this manner for a few days were further disheartened by seeing signs of hostile Indians.

They at last succeeded in reaching an abandoned cabin, on which they found a notice posted, saying that the Indians were again murdering the whites, and warning settlers to flee to the nearest fort. Thus, Mr. Harvey and his partner tied up the scow and immediately started for Port Madison, intending to return as soon as possible to save their property. Everything was lost before they could return.

Sometime later in the year of 1859, Mr. Harvey returned to Snohomish and purchased the claim of E. H. Tucker (160 acres). He paid $50 for full possession, including the little “shack” which had been built. Harvey and Howe settled on adjacent claims across the river from Snohomish City. Mr. Harvey soon discovered that he had a valuable piece of property from an agricultural standpoint, and also realized its favorable situation in a financial sense. He knew the property would increase in value as the village of Snohomish grew and became more important. His full time was subsequently employed in clearing and improving this place, which abundantly repaid the care bestowed upon it.

He built a log cabin, which soon became a welcome sight to the river travelers. Harvey’s Homestead documents state that he had resided on this property since January 1, 1860. The property is located on the south side of the Snohomish River, directly across the river from the City of Snohomish. Harvey spent all of his time clearing and improving his homestead. The mills removed the big logs around the edges of the river, and all that was left were the treetops and stumps. There were no explosives, no modern machines, not even large horses. All stumps had to be pulled out by hand when possible. Some farmers had oxen that could be used.

After getting some of the land cleared, homesteaders were able to raise potatoes and other crops. Harvey was able to obtain sheep, cows, and oxen and was able to gradually build his livestock herd. He planted fruit trees, and improved the property over the years.

The U.S. Government was wary of new homesteaders, because many of them would give up and return to their native homeland, or go to work at a mill, etc. The government wanted proof that the homesteaders would stay on the land, be good citizens, improve the land, and not abandon it. Two people from the government would travel to a new homestead and make a report on the progress of the farm. This took place around 1877 for John Harvey.

On the Final Homestead Proof document, it states that before June of 1869, Mr. Harvey made settlement on said land and built a two-story house of lumber, about 35 feet square with a shingle roof, tongue and groove dressed floor, 2 doors, and “12 or 14” (as stated in the document) windows. A wood stove heated the house. The document states that it was a “well furnished and a comfortable house to live in.” The document also states that Mr. Harvey had cultivated 50 acres of land, built a 70-square-foot barn with other out-buildings and had an orchard of about 100 fruit trees.

Under the terms of the Enabling Act authorizing the creation of Snohomish County, passed by the assembly of the Territory of Washington, January 14, 1861, Mr. Harvey was named as member of the Board of County Commissioners. This Board was delegated to organize the county; the other members of this historic commission having been Emory C. Ferguson (known as E. C. Ferguson) and Henry McClurg. Mr. Harvey also rendered service as the first Treasurer of the county and in other ways was a useful personal factor in getting the county government started. His interest in the general industrial development of the community likewise was manifested in a direct and intelligent manner.

In the Statutes of the Territory of Washington, 1865-66, the legislature again referred to John Harvey. There was an Act to Incorporate the Snohomish City Mill Company in 1866. Harvey was named as one of the City Mill’s original six commissioners. He did this along with Clark Ferguson (brother of E. C. Ferguson), W. B. Sinclair, M. L. King, E. C. Ferguson, and Charles Short. The mill was located on the Harvey property, and there is still a mill running in that same location today. The mill is located on the east side of Airport Way adjacent to the Snohomish River, just south of the city of Snohomish.

In the History of Skagit and Snohomish Counties, Washington published in 1906 there are several references to Harvey. The most interesting is a story attributed to E. C. Ferguson, who told about an incident involving John Harvey. John Harvey’s farm was across the river from the present city of Snohomish. He owned a sloop that would transport about 200 bushels of potatoes over to Port Gamble, which was the principal market for this part of the Sound country. Harvey had in his employ an English sailor named John Murphy who had deserted ship and Harvey agreed to help him out. In the fall of 1867, Murphy persuaded Mr. Harvey to allow him to take a load of potatoes to Port Gamble in the sloop. The trip was made in safety, the potatoes were sold and delivered and the return voyage begun.

At the mouth of the Snohomish River was a hotel and saloon run by Perrin Preston. Murphy stopped off and had a few drinks and swapped yarns with the rest of the saloon’s clientele. As the evening wore on, Murphy soon became disabled. In the morning, he discovered that the sloop had broken from its moorings and disappeared. Instead of trying to find it, he continued with his carousing for the next two days. At that point, Harvey arrived looking for his boat and sailor. Murphy was dead drunk and the proceeds of the potato sale were squandered. Eventually, the boat was found beached on an island across the channel from Preston’s saloon.

Harvey is alleged to have returned home, considered the loss of the cargo of potatoes, the expense of finding and recovering the boat, and the loss of time he personally had to expend to restore things to normal, and concluded that Murphy should be charged by the law. After consultation with the local Justice of the Peace, the charge was eventually established as “piracy on the high seas.” A warrant was issued and the constable was sent to bring in Murphy, who was still at Preston’s saloon.

Eventually, the case was heard before the justice of the peace. The story was told and there were no witnesses called. The justice reflected (momentarily) and then proceeded to sum up the evidence and conclude that the prisoner was guilty and the decision of the court was that he should be hung by the neck until he was “dead, dead, dead.”

Murphy had asked Mr. Ferguson to go with him to see that he had a fair trial. Ferguson stood up and pointed out to the justice of the peace that his court did not have jurisdiction to try a piracy case, and furthermore, his level of authority did not even have the right to issue a capital sentence. At that point the “judge” said, “Well, if I can’t hang him, then I’ll turn him loose.” And that ended the proceedings.

Eldon Harvey remembers when his father, Noble Harvey, asked an aged Indian woman if she remembered his grandfather. The woman lived in an Indian camp on a gravel bar across the river from where Eldon was born in the homestead house. She told Eldon’s father, Noble, that she did, indeed, remember his grandfather. The old woman told them in Chinook that John Harvey was one of the first white men in the area, and “he was a bad man from Boston with his gun.” History shows that John Harvey did have more than one encounter with local Indians, but history also shows that few other people would have described Harvey as “bad,” nor was he from Boston. “Boston man” was a common description used by the Indians to describe the [American as opposed to British] white settlers.

According to records at the Morman Library, John Harvey married Mary Ann Stewart on March 28, 1869. The 1870 Federal Census indicates that Mary was nine years younger than John, and that she was from New York. Whitfield’s History of Snohomish County states, “In passing, it may be well to record that the first divorce of which mentioned [sic] was made in the books of the County was issued August 19, 1871, by Orange Jacobs, Judge for Kitsap, King and Snohomish Counties, the case being that of Mary Ann Harvey vs. John Harvey.”

(At the time of the divorce, Harvey owned 32 head cattle, six swine, and some poultry, hay, and grain on his homestead.)

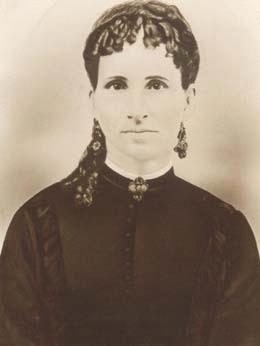

A year or so after the divorce, Harvey had become nicely settled on his place, and he married Christina Noble, an estimable lady, who was born in Fredericton, New Brunswick, on March 9, 1839. They were married in at the Presbyterian Church in Seattle on July 10, 1872, which was one of the first marriages noted in Snohomish County. (The First Presbyterian Church in Seattle was established on December 12, 1869.) I often wondered how they got to Seattle at that time and recently found the answer. In 1872, a regular steamboat service was established between Snohomish City and Seattle. This service continued until 1890. At that time, Snohomish was the main river port and logging center on the Puget Sound.

A number of Christina’s relatives resided in Puget Sound area at the time. Christina’s sister, Mary Noble Adair and her husband Alex arrived in Washington Territory on September 9, 1868. Mr. and Mrs. Adair lived in Seattle for two years running at the old Occidental Hotel, which was located in Pioneer Square. On September 19, 1871, the Alexander Adairs settled at Novelty on their 160 acre homestead. I assume that when Alexander Adair canoed to Snohomish to do his trading, he had become friendly with John Harvey and must have introduced John Harvey to his sister-in-law, Christina Noble.

In 1876, Mr. Harvey built a two-story house near the log cabin site and the river. There was a fence around the inhabitable area and lots of animal pens. There was a notice in the Northern Star dated June 23, 1877, that Mr. Harvey was building a small warehouse on the opposite side of the river.

Mr. and Mrs. Harvey were among the 15 charter members of the Presbyterian Church, the first church in Snohomish County. The church was established at a meeting held on April 4, 1876. At that time, Snohomish was just a little village of about 100 men and 10 women. They were of great help to the Church and donated the chairs and hanging lamps as well as other contributions. Church records show that on September 2, 1877, the first new members taken into the Church were Christina’s sister, Mary Noble Adair, her husband Alex, and their two children, John Harvey Adair and Dora Louisa Adair.

John and Christina Harvey had only one child. Their son, Noble George Harvey, was born on June 17, 1873. He was the first white baby boy born in Snohomish County.

One amusing incident told by John Harvey to his son, Noble, was a winter story. Winters were much more severe in those days; and at one time, fences were built from split cedar and fastened together with whatever nails or pins one could get. In order to take care of the sheep, the pens had to be portable, so that the sheep could be moved from one place to another or even inside if the weather demanded. For a gate, there were boards set up across from one post to the other.

At one time, the snow was very deep. When you put two goat, sheep, antelope, deer or elk together, they fight for dominance. They would stand up on their back feet and bang their heads together, and the winner was the established leader. John had stooped over to pick up one of the bars from the gate, and a buck mistook John’s backside for another threatening sheep, and bucked him, driving John’s head into a snowdrift. When John backed up to get out, the sheep was ready for him, and hit him again and again. John was able to escape before he smothered in the snow.

Another story was that there were two men who homesteaded just west of John Harvey’s property along the river. They were progressing quite well and clearing the land, when two Indians came in asking to dry their powder for their rifles in the farmer’s ovens. The men were very congenial, spread the powder in the ovens for the Indians. They were promptly jumped and killed by the Indians.

People coming down the river by canoe would stop and visit at the Harvey house. Several women gave birth there, because there were no doctors nearby. John’s wife, Christina, was a midwife. One of the children born there was a niece of Christina and John Harvey. Her name was Dora Luisa Adair, who was the first white child born in Snohomish County, on September 22, 1871. Her parents were Alexander and Mary Noble Adair, who were residing on a homestead in Carnation/Duvall area at the time. The mode of transportation from the Adair homestead to the Harvey property was by canoe. The Adair claim was adjacent to the Snoqualmie River.

John Harvey was one of the pathfinders of the Puget Sound country, being in the vanguard of those pioneers who first settled in and around Seattle. He went before, felling trees and clearing the way for the coming of future hosts of civilization, who now enjoy and reap the reward of those early endeavors. While Mr. Harvey had much confidence in the ultimate outcome of the settlement, he perhaps hardly dared dream that the development to which he looked forward to would ever reach the point it is today.

John Harvey died on November 28, 1886, after a lingering illness at the age of 58 years. Christina Harvey, with the aid of her 13-year-old son continued to run the farm. Christina died a few years later of typhoid fever, on September 17, 1892, at the age of 53. Their son, Noble, was 19 years old when he took over the management of their homestead and made many improvements on it.

The Harvey Family is still living and conducting business, known as Harvey Airfield, on 80 of the original 160 acres of John Harvey’s homestead.