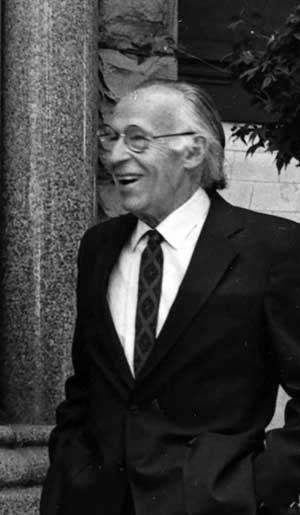

Architect Victor Steinbrueck, perhaps best known for his efforts to protect Seattle's historic Pike Place Market and Pioneer Square, worked to adapt modern architecture to reflect the Puget Sound region's unique character. His devotion to his craft, colored by his passionate belief in socially conscious design, directed his life's work and many civic actions.

Lifelong Sketcher

Born in Mandan, North Dakota, Steinbrueck came to Seattle in 1913. He grew up in the city, and in 1928 entered the University of Washington. He began studying at the University's School of Fisheries, but in 1930 changed his academic course to architecture. He graduated in 1935.

Steinbrueck began his lifelong practice of sketching during the Great Depression, while a part of the Civilian Conservation Corps, a federal agency that employed out-of-work designers and engineers (among others) to build roads and improve parks. Throughout his years of civic life in Seattle, Steinbrueck used loose ink sketches to illustrate and explain publicly the relationship between Seattle residents and their urban environment.

Prior to World War II, Steinbrueck worked in a number of Seattle architectural firms including William S. Bain, Sr. in 1935, J. Gordon Kaufmann in 1936, and James Taylor in 1936. In 1938, he began private practice and played a part in the Yesler Terrace Housing Project (1940-1943, Aitken, Bain, Jacobson, Holmes and Stoddard) before serving in the military from 1942 to 1946.

Upon his return to Seattle, Steinbrueck joined the architecture faculty of the University of Washington. For two years beginning in 1962, he served as acting chair of the Department of Architecture.

In his buildings, Steinbrueck developed his vision of regional modernism. Like Steinbrueck, many American architects embraced modernism after World War II. Modern architecture broke away from historical traditions, stressing functionality. Typically, modern houses of the period possessed clean lines and rectangular spaces, and were free of ornamentation. As Americans returned from the front to settle down, "modern" design suited the needs of Post War America.

Regional modernism, a local interpretation of the larger style, employed local materials and construction methods in the service of modern design. In many examples, regional modern architecture worked with the conditions of the building site, emphasizing the outdoors with large panes of glass. Many of Steinbrueck's modern regional house designs were modest, including:

- The Alden Mason residence (1949)

- The Victor Steinbrueck residence (Seattle AIA Award, 1949-1953)

- The Alden residence, Richmond Beach (Seattle AIA Award, 1951, destroyed)

- The William T. Stellwagan residences (1951-1955)

- the Earl L. Barrett residence (1954-1956)

- The Frederick Anderson residence (1958)

- The T. H. Terao residence (1959 - 1961, altered)

Steinbrueck's firm, along with Paul Hayden Kirk and Associates, also designed the Faculty Center Building (1958-1960, Seattle AIA Award 1960) which exemplifies regional modernism with its open forms, sweeping horizontal lines, and extensive use of glass.

Preservationist

Although Steinbrueck received a number of awards for his designs, his dedication to the preservation of Seattle is arguably his most important life's work. Steinbrueck played a leading role in many of the historic areas now synonymous with Seattle. He contributed to the final design of the Space Needle conceived by John Graham Jr. (1908-1991) for the 1962 Century 21 Exposition.

Steinbrueck actively supported the preservation and adaptation of Pioneer Square and Pike Place Market. He sought to protect the historic fabric of these centers, while successfully fighting to incorporate low-income housing and social services within their comprehensive plans.

Steinbrueck used his sketches and writing to argue his urban ideals. His books Seattle Cityscape (1962), Market Sketchbook (1968) and Seattle Cityscape #2 (1973) demonstrated Steinbrueck's views of the city. His drawings and narratives humanized social and architectural issues. He also founded Friends of the Market to fight plans for the "renewal" of the historic commercial center.

His interest in truly "public" space extended to parks. Steinbrueck, with renowned landscape architect Richard Haag (b. 1923) designed a number of parks including:

- Capitol Hill Viewpoint Park (1975) now Louisa Boren Park

- Betty Bowen Viewpoint (1977) also Marshall Park

- Market Park (1981-1982) now Victor Steinbrueck Park

Steinbrueck's urban ideals were part of a larger movement begun in earnest in the 1930s as a reaction to the negative effects of progress and modernization. Steinbrueck's legacy continues in Seattle's growing preservation community and in the rising popularity of local history.