The city of Renton, located some 12 miles southeast of downtown Seattle along the southern shores of Lake Washington, began as a center for extraction industries and, later, manufacturing. Over the years it has been the hub of many transportation corridors – from rivers to highways, rails to skyways. Long before non-Native settlers came to the area, the Duwamish tribe had a village at the present site of Renton, near the confluence of the Black and Cedar rivers. The Cedar River flowed from the southeast into the Black River which, in turn, flowed into the Duwamish River, which ran north to Seattle’s Elliot Bay. Early in the twentieth century, this configuration was changed by human engineering, but at the time the rivers were important resources and avenues of trade. The first non-Native settlers arrived in the area in the 1850s, about the same time the Denny Party and others made Seattle their home. The town of Renton was first platted in 1875 and incorporated as a fourth-class city in 1901. At that date, the population numbered barely more than 1,000 souls, but quickly doubled. During World War II, the population mushroomed to 16,000, three and a half times its pre-war numbers, as airplane and tank manufacturing drew large numbers of newcomers. From there, Renton continued to grow, both through new arrivals and via annexation. By the turn of the twenty-first century, the population numbered 50,000 and, as of 2024, the number had passed 100,000. Annexations have included North Renton, Kennydale, Benson Hill, Earlington, the Talbot Hill area, and the Highlands, as well as many smaller parcels. In 2011, the city became a "majority minority" city, with a greater number of racial minorities than whites.

Staking Claims

In 1853, Henry Tobin (d. 1855/1856) paddled up the Duwamish River and, upon seeing the meeting place of the waters, staked a claim. The running waters were a perfect location for a mill, and access to the lake provided potential for all kinds of business opportunities. Shortly thereafter, another newcomer, Dr. R. H. Bigelow, who had settled next to Tobin, discovered a coal seam on or near his property. Tobin mill was built to provide timber for the mine which Bigelow and his partners named The Duwamish Coal Company.

Soon, the influx of non-Native settlers into the region interfered with the Indians' way of life. Some tribes tried fighting back in what became known as the Indian Wars or Treaty Wars, which lasted for only a few months during 1855 and ended with the forced resettlement to reservations of most of the Indians within the territory. During the short war, Tobin’s mill was burned to the ground and settlers were driven away. Tobin died of ill health and the mine shut down operations after delivering only a few loads of coal to the bunkers on Elliott Bay. Nonetheless, Bigelow’s find is significant as the first coal-mining enterprise in King County.

Erasmus Smithers and the Founding of the Town

In 1857, landowner Erasmus Smithers (1829-1905) met and married Tobin’s widow, Diana, who held the patent on her husband’s claim. Between them they ended up owning nearly 500 acres of land. In the ensuing years, more settlers moved to the area; by 1867 the community then known as Black River, or Mox La Push by the Duwamish, rated its first post office.

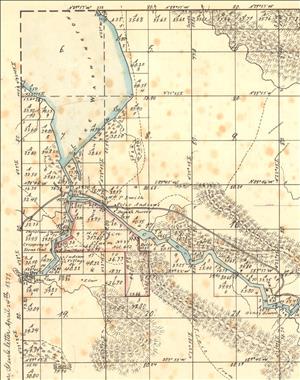

Two decades after the demise of Bigelow’s mine, in 1873, Smithers and others discovered, or re-discovered, coal in the area. He and his partners obtained the financial backing of Captain William Renton (1818-1891), a wealthy investor, and agreed to name the mining operation, as well as the planned town, after him. It is not clear if Captain Renton ever set foot in his namesake town. Smithers filed the first plat map for the Town of Renton on September 5, 1875. The map encompassed 28 blocks and a grid of named streets. It included a right-of-way for a hoped-for railroad. This first plat covers what is still the core of Renton’s downtown district.

Other coal mines soon dotted the hills and mountains east of Renton, but access to the lake and the rivers allowed Renton to become the hub of the local coal industry. Men drawn to work in the mines included white and Black settlers, Chinese immigrants, and Native Americans. By the early 1900s, Renton was a prosperous town in many ways. Earlier, it had been known as a rough-and-tumble community, due to the nature of the extractive industries. In 1885 there were nine saloons and no churches. The Seattle Car Manufacturing Co. (later Pacific Car and Foundry and then PACCAR) relocated to Renton in 1908. By 1910 the town had churches, schools, newspapers, and a bank. The Renton Mine, which had been operated by several different concerns, closed for good in 1920. However, other industries included brick, briquette, and tile plants, a cigar factory, a glass-making facility, a twine plant, a pasta factory, and lumber mills led the Chamber of Commerce to proclaim Renton the "Town of Payrolls." Farmers in the fertile agricultural land in the river valleys to the south looked to Renton as a commercial center.

Defined by Water

Renton’s geography – surrounded and even bisected by waterways – has had a big hand in the town’s development.

In 1899 the City of Seattle set its sights on the Cedar River to solve its water shortage problem. Within a few short years city engineers built a pipeline that siphoned off water from the river and ran 28 miles from the headworks to the city’s reservoirs. The pipeline ran directly under the City of Renton, which received none of the water. (Renton obtains the bulk of its water from wells.) While the pipeline ran under Renton, the Cedar River ran right through the town (and still does). Flooding was a constant threat in the early decades. The worst disaster occurred in the fall of 1911 when the dam holding back rainwaters at Landsburg failed and the swollen river came rushing down through town, taking out several bridges and swamping city streets and homes. Renton residents ran for their lives as emergency sirens blew. One resident, Dail Butler Laughery, remembered the fear:

"The siren started to blow with its loud screech and wail that turned our blood to water and shivers ran up and down our backs when the first word of the dam breaking hit Renton, and it was about to blow as long as there was any danger of the flood that followed. It blew weirdly, loudly and mournfully for three days and nights" ("A Landscape Transformed").

The event spurred plans to re-engineer the river, dredging and channelizing it away from its confluence with the Black River and directly into Lake Washington. For a few short years, the Cedar and Black rivers ran parallel to each other, although in different directions. That all changed in 1916 with the completion of Seattle’s ship canal between Lake Washington, Lake Union, and Puget Sound. As the waters merged, Lake Washington’s water level fell by about 9 feet, causing the Black River to dry up, leaving only remnants of stagnant water. With the demise of the Black, the Cedar became and remains the only outlet to the lake at the south end. The Sammamish River feeds the lake from the north end.

The death of the Black River was devastating to many. In a letter to her friend, journalist Lucile McDonald, historian Morda Slauson described the ecological and human cost of the loss:

"The most disastrous thing which happened was the wiping out of an entire salmon run. I have had many Renton folks who remember tell me how sad it was to watch the beautiful Black River turning into a mud hole. Henry Moses, last of the Duwamish, who died in January said he took his dugout canoe which his grandfather had made for him and hid it in the brush one day and never paddled it again. He couldn’t bear the thoughts of using it in any stream but the Black" (Slauson to McDonald).

All Roads Lead to Renton

Renton was one of the first outlying communities to be connected by road to Seattle. By the end of the nineteenth century, Renton was also a railway hub. The first railway, the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad, arrived in 1877, stopping at the Black River Junction and Renton depots. It never made it all the way to Walla Walla. Within a few short decades, the city found itself ringed by rail lines: the Seattle-Tacoma Interurban train allowed Renton to serve as a bedroom community for the larger city; the Belt Line ran up the east side of Lake Washington to Woodinville; and a line utilized by several companies, and perhaps best remembered as part of the Milwaukee Road, pushed through Renton toward the mining communities to the east. In addition to steam and diesel rail, an electric streetcar ran from Seattle along the west side of the lake to Renton between 1891 and 1936 on a route that would later become Rainier Avenue.

As rail travel gave way to freeways, Renton was again at the hub – or, some might say, in the crosshairs. Interstate 405 brought its infamous S-curves through the heart of town before turning north toward Bellevue and points beyond. Construction of 405 began in 1956 and seems to have never stopped. In 1999 the city adopted the slogan: "Renton: Ahead of the Curve." Meanwhile, Highway 167, aka the Valley Freeway, has been a longstanding north-south route from Renton to Kent and beyond. In addition, State Route 900, part of the historic Sunset Highway, and State Route 169, the Maple Valley Highway, take off from Renton to the northeast and southeast, respectively. Several major highway interchanges often snarl traffic in the city.

The Boeing Factor

Probably the largest influence in Renton’s development began in the 1940s when Boeing moved to town. In 1941, the Boeing Airplane Company moved in and set up shop near the shores of Lake Washington. During World War II, the Boeing Renton plant was turning out B-29 Superfortress bombers at a peak rate of six per day. At the same time Pacific Car and Foundry (renamed PACCAR in 1972) was churning out 30 Sherman tanks a month. Within a few years, Boeing began developing jet transportation, beginning with the Dash 80 (367-80) and moving on to the 700 series commercial jets. The Renton facility became the site of 737 assembly from 1967 to the present. To this day, visitors to the town may be startled by the sight of Kansas-built 737 fuselages traveling by rail through town at street level on their way to the Boeing plant. Today, Boeing and other industries still pump millions of dollars into the local economy. Some refer to Renton as the "Jet Capital of The World."

Changing Demographics

In the second half of the nineteenth century, Renton went from a handful of non-Native settlers living alongside Duwamish Indians to a thriving, if still small, township built on logging, coal mining, and small-scale manufacturing.

Chinese workers in the Renton area mines faced discrimination and expulsion in the 1880s. Beginning in the twentieth century, an influx of Japanese immigrants settled in the farmlands surrounding the town. Anti-immigrant sentiment continued as white residents complained about the foreigners in their midst. In 1900, a petition by Renton citizens against the use of Asian labor on county road projects was turned away without review by King County commissioners. In 1923, the Ku Klux Klan brought its nativist and anti-Catholic ideology to town, holding a "Konvention" at a park near Renton, no doubt in response to the influx of large numbers of Italian and Eastern European immigrants to the area.

Meanwhile, many Native Americans had been pressured into moving to reservations, although a few families in the Renton area held out. The Moses Family was one of these. Jimmie Moses (1847?-1915) and his wife Jennie (d. 1937) continued living on their homestead on the Black River, although, according to white law, it now belonged to the Smithers family. Their three sons attended Renton schools. The family was locally famous, and were recognized as leaders of the Duwamish tribe. Henry Moses (1900-1969) recalled his childhood on the river:

"When I was a boy there was an Indian village about where the Renton Shopping Center is now and another at Elliott on the Cedar. The Indian cemetery was at the fork of the Cedar and the Black. There was wonderful fishing in the Black River, trout up to two feet long. All the Renton boys, both Indian and White, fished and paddled canoes up and down it. Our family always kept a cedar dugout tied to our porch" ("Last Tribal Chief").

The influx of workers during World War II brought even greater diversity to the city. Temporary housing was erected on a large scale to the east of the city center in what came to be known as the Renton Highlands. Many of the so-called "temporaries" still exist. Black families had started moving to the city at the turn of the century, many settling in an area of the Highlands called Hilltop.

War industries brought many more Black workers to town. At the same time, the Japanese Americans who had farmed, raised dairy cattle, and set up nurseries in and around Renton were forced out by Executive Order 9066 early in 1942 and relocated to concentration camps for the duration of the war. Many never returned. At the end of the war, the city officially annexed the war worker housing in the Highlands, adding 7,500 residents to its population. Renton now qualified as a second-class city.

As the twenty-first century approached, many new immigrants arrived in Renton, many from Asian countries, Latin America, and the Middle East. By 2011, Renton was officially a "majority minority" city. City government has stepped up to the challenge of serving a highly diverse population with outreach, focus groups and special events, as well as a race-blind hiring policy.

Branching Out

Renton’s first hospital was a modest structure set up in 1911 by Dr. Adolph Bronson (1877-1938) in the downtown core. In 1945, a new hospital opened on Rainier Avenue. Affectionately known as the Wagon Wheel Hospital for its distinctive design of seven radiating wings off a central courtyard, Renton Hospital served the region until 1969, when a more modern facility was built in the valley to the south. Valley General Hospital became Valley Medical Center in 1984. A number of other hospitals and medical clinics sprung up around the area.

The valley area to the south of old Renton, once farmland, has proved fertile ground for light industry, retail, administrative structures, and hotels, in addition to medical facilities. The Swedish retailer IKEA brought its sprawling showroom to the area in 1994. In 2008, the Federal Reserve Bank opened a branch there.

On the north side of town, the Shuffleton steam plant, constructed in 1929 on the shores of Lake Washington, ceased operations in 1989 and was imploded in 2001, making way for an upscale hotel, apartment, and office space complex called Southport. Nearby The Landing in Renton shopping center took shape on undeveloped land once owned by Boeing. The fantasy game publisher Wizards of the Coast has headquarters in North Renton. The area also is home to big box stores and several PACCAR facilities, including Kenworth Trucks. A Topgolf complex recently went up adjacent to The Landing.

Renton’s downtown historic business core, centered on 2nd and 3rd avenues, struggled for many years as shoppers were drawn to the malls and big-box stores in other areas. The "Boeing Bust" of the early 1970s naturally took a big bite out of Renton’s economy. City-sponsored revitalization efforts began at the start of the twenty-first century and included converting an auto dealership into a premier events center known as the Pavilion. A nearby plaza area called the Piazza hosts a farmers market and other events. A parking garage and new apartment buildings were erected adjacent to a new regional transit center.

Ecology of the City

As noted above, Renton is defined by water and waterways. In addition to its river and lake shorelines, the city is surrounded by numerous wetlands including the remnants of the Black River, now found in an area called the Black River Riparian Forest, and the Springbrook and Panther Creeks wetlands to the south. During the 1980s, the city embarked on a major effort to acquire wetlands in the valley south of Interstate 405. In partnership with the state Department of Transportation (WSDOT), Renton took steps to preserve the wetlands for flood storage and filtration.

In addition, the lowering of Lake Washington in 1916 turned the lake’s southern shoreline into marshland, much of which has now been filled and claimed by the municipal airport and the neighboring Boeing plant. In recent years, plans have been laid to restore the armored shoreline to some semblance of nature in order to provide habitat for Chinook salmon and other species.

Farther along the east side of the lake, part of the old Barbee lumber mill site has been designated a Superfund site and awaits expensive clean-up due to contamination of the land by creosote.

Community and Recreation

Renton’s first major festival was known as Frontier Days, and true to its name, it espoused a Wild West theme, including a rodeo. Frontier Days, later called Western Days, began in 1939 and lasted into the 1980s. In 1985 the city inaugurated Renton River Days with a more culturally inclusive scope.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, Renton was famous for "The Loop," a teen tradition of cruising up and down the city’s main downtown streets. One stop along The Loop was Rollerland, an Art Deco-style skating rink on Rainier Avenue, which burned down in 1963.

From 1992 to 2007, Renton was home to the Spirit of Washington Dinner Train, an excursion rail experience that utilized the old Belt Line tracks to take guests to the Sammamish Valley wineries and back.

For many decades, Renton may have been best known as the location of Longacres racetrack, which opened in 1933 and closed in 1992. While the thoroughbreds may be gone, sports are still very much part of the culture of the city. In 2024, the former racetrack become the training facility of the Seattle Sounders soccer team and is known as Sounders FC Center at Longacres. Meanwhile, the Seattle Seahawks football team constructed their training facility, the Virginia Mason Athletic Center (VMAC), on Renton’s lakeshore in 2008. Maplewood Golf Course has been in business since 1927; it was acquired by the city in 1985. The Henry Moses Aquatic Center, in Liberty Park, was named for a member of the Duwamish tribe whose family was a fixture in Renton for many decades. The old Milwaukee Road rail line has been converted to a walking/biking path, the Cedar River Trail, as has a long stretch of the old Belt Line. The pride of the city’s extensive park system, Gene Coulon Memorial Beach Park, meanders along the southeast shore of Lake Washington where a railroad spur once took coal and lumber to waiting ships.

For many, the Renton downtown library, built in 1966, (now part of the King County Library System) is memorable for its location straddling the Cedar River. The Renton History Museum occupies a decommissioned Art Deco-style firehouse.

A Federal Case

In the 1980s Renton found itself on the national stage when a case involving pornographic films wound its way through the judicial system and ended up at the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1981, the city had passed an ordinance designed to keep adult entertainment out of the downtown area via strict zoning restrictions. When porn mogul Roger Forbes elected to ignore the ordinance and show adult films at the Renton Theater, a group of citizens banded together to pressure the city into enforcing the ordinance. A series of court filings, both in King County Superior Court and in federal courts, turned on the definition of obscenity and the use of zoning. Ultimately, the City of Renton v. Playtime Theatres, Inc. came before the U.S. Supreme Court. On February 25, 1986, that body handed down a decision affirming the right of local governments to regulate the location of adult entertainment.

Rubbing Elbows

Renton has had several brushes with famous individuals. Aviator Wiley Post (1898-1935) and humorist Will Rogers (1879-1935) took off from Renton Airport (generally called Bryn Mawr Air Field at that time) on August 7, 1935, on what was to be a marathon trip across the Northern Hemisphere. Tragically, the two perished a week later when their seaplane crashed near Barrow, Alaska. In 1949, the City of Renton dedicated the Will Rogers-Wiley Post Memorial Seaplane Base at the northern tip of the airport.

Renton-raised boxer Boone "Boom Boom" Kirkman (b. 1945) made a name for himself in the ring during the early 1970s. Rumor has it that famed actor Clint Eastwood (b. 1930) once worked briefly as a lifeguard at Kennydale Beach Park, likely about 1950. Sally Jewell (b. 1956), a graduate of Renton High School, went on to an executive career at REI (Recreation Equipment, Inc.) and then served as Secretary of the Interior under President Barack Obama from 2013 to 2017. Karel Shook (1920-1985), internationally recognized dancer, instructor, and choreographer, was born and raised in Renton. He was one of the founders of the Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Renton’s most famous resident never lived in Renton. Superstar musician Jimi Hendrix (1942-1970) died in 1970 and was buried in his family’s plot at Greenwood Cemetery in Renton’s Highlands. What was a simple grave was transformed into an elaborate memorial in 2002.