On August 26, 1856, U.S. Army Captain George Pickett (1825-1875) arrives on Bellingham Bay from Fort Steilacoom to construct a military installation. Pickett’s job is to build a fort that will deter the attacks by “northern Indians” on the bayside villages of Whatcom, Sehome, and Fairhaven. Fort Bellingham will bring prestige and security to the area.

Unrest Prevailing

In the mid-1850s, Indians from Canadian and Russian territory threatened settlements at Whidbey Island, Port Townsend, Bellingham Bay, and the San Juan Islands. The Indians came south in war canoes from the Queen Charlotte Islands, southern Alaska, and what is now the north coast of British Columbia.

With unrest prevailing throughout Washington Territory, the newly reconstituted Ninth Infantry Regiment sent George Pickett to build a fort on Bellingham Bay to establish a U.S. military foothold and protect the region’s resources. The 68 men of Company D, mostly Irish and German immigrants, accompanied him. First Lieutenant Robert H. Davis (1824-1865), nephew of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, and Second Lieutenant J. W. Forsythe (1836-1906) who in 1890 would gain infamy at Wounded Knee, were on his staff.

The site for the new fort was located on a prairie above a bluff. It was the only open space on the bay and had an "excellent" spring, but a homesteader already occupied it. Maria Roberts, whose husband was away, refused to give up their claim, so the troops removed her roof. She had no choice but to walk the three and half miles to Whatcom even though she was many months pregnant. Later, she and her husband were allowed to build a cabin on the beach, where they remained for years.

Building the Fort

Work began immediately. The soldiers dug latrines, garbage pits, and the trenches for the palisades. Pickett hired three civilians from Whatcom at $4.00 a day to do the finish carpentry.

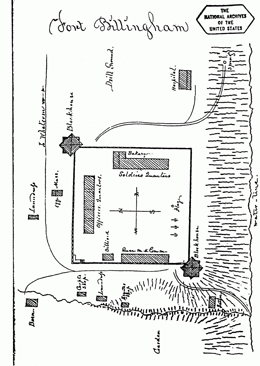

"The Barracks, storehouses & officers quarters, are within an enclosed square, of about 80 yards the side," Inspector General Joseph Mansfield wrote in his report of December 1858. The fort is "made of pallisades [sic] set in the ground, loopholed for musketry and flanked by two Blockhouses two stories high, pierced for mountain howitzers and loopholed: and is provided with 3 gates -- All the buildings are one story."

Mansfield added that the officer’s quarters were roomy and that "The buildings were wood framed. Barracks had a mess hall, & kitchen, & bakery attached, and was ample." The blockhouse near the shore was "occupied" by the guard.

A Life of Drudgery

The other blockhouse served as a jail, which was often filled. At the time of Mansfield’s inspection, four men were confined for desertion. Other buildings included a hospital with six iron bedsteads, two wardrooms and kitchen, laundresses’ houses, carpenter and smith shops, a barn, an outhouse, and a sutler’s store (in the nineteenth century, a store licensed to sell to the military). The fort also had a large garden. Officially, Pickett lived at the fort, but he spent most of his time in a small house he had built in the village of Whatcom.

The soldiers lived a life of drudgery at the fort, performing manual labor such as digging and gardening in addition to drilling. Desertions were as frequent as infractions and the jail was always occupied. The soldiers performed poorly with their muskets. When they were asked to shoot at a target 200 yards away, only one out of 40 hit the target. "This showed the want of instruction & practice," Mansfield remarked.

The Pig War Intervenes

In July 1859, trouble broke out on San Juan Island when an American settler, Lyman Cutlar, shot a Hudson’s Bay Company pig. When the Department of Oregon commander, Brigadier General William S. Harney learned that British authorities in Victoria had threatened to arrest Cutlar, he dispatched Pickett’s company to the island to protect American interests. In response, the British sent several warships. While the opposing force that summer was facing off at San Juan Island, Pickett’s men dismantled pieces of Fort Bellingham (including one of the blockhouses) and reassembled them on the island’s southern shore.

When the British and American governments agreed to joint occupation of San Juan, what remained of the Fort Bellingham was removed piecemeal by the various units occupying the island. In 1861, the Territorial Legislature asked the federal government to post at least one company at the fort in order to keep it open, but the request went unheeded and in 1863 the fort officially closed. Only the blockhouse on the northwest corner and a few other structures remained as evidence that the post ever existed. In 1868, the Army returned 320 acres to Mrs. Roberts, now remarried as Mrs. Tuck. She lived there for many years and farmed the land.

Rows of greenhouses of a wholesale nursery dominate the site today (2004). But a closer examination reveals traces of the old fort. The blockhouse burned down in 1897, but sandstone steps mark the path between the officer’s quarters. Two walnut trees, said to have been planted in Captain Pickett’s time, still live.