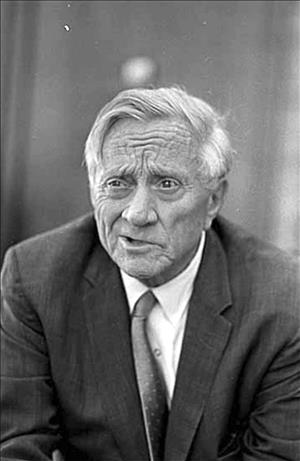

William O. Douglas, who grew up in Yakima, was appointed to the United States Supreme Court at the age of 40 and served for more than 36 years, longer than any other justice in the Court's history. Both on and off the Court, Douglas was outspoken in his support for individual rights and for preserving the natural environment. Coming from a poor background in rural Eastern Washington, Douglas saw himself as a champion of the underdog against the rich and powerful. He defended the rights of the individual against government and corporate power as fiercely as anyone who has ever sat on the Court and enshrined the concept of a constitutional right to privacy in the law of the land. A love for wilderness honed on boyhood hikes into the Cascade Mountains near Yakima made Douglas an early leader of the environmental preservation movement. Douglas was criticized for his views, but also for the quality of his legal opinions, his three divorces, and some of his financial dealings. Throughout his dramatic and controversial life, Douglas returned regularly to the Northwest to spend his summers in the Wallowas and Cascades.

Yakima Boyhood

William Orville Douglas was born on October 16, 1898, in the town of Maine, Minnesota. He was the second of three children of William and Julia Douglas. His older sister Martha was born in 1897 and his brother Art in 1902. Douglas nearly died from a high fever shortly before his second birthday and was seriously ill for weeks. On their doctor's advice, his mother massaged his arms and legs with salt water every two hours throughout the illness to prevent atrophy. Although years later Douglas claimed the disease was polio (infantile paralysis), his most recent biographer, Bruce Allen Murphy, has demonstrated convincingly that it could not have been polio (Murphy, 620-622).

Douglas's father, a Presbyterian minister, was frequently ill himself. He moved the family to Estrella, California, in 1902. Two years later, they moved to Central Washington, following several of Julia's relatives who had settled in North Yakima (now Yakima). Reverend Douglas found a position serving churches in the small farming communities of Cleveland, Bickleton, and Dot in Klickitat County.

Within months of the move to Cleveland, the senior Douglas died on August 12, 1904, following stomach surgery intended to relieve his ulcers. Julia Douglas moved with her children to North Yakima to be near her family. She bought a house on North Moxee (later North Fifth) Avenue with some of the insurance money from her husband's death and invested the rest. Julia frequently told her children that her lawyer had lost the invested money and that they were penniless, but in fact a number of the investments were reasonably successful. Nevertheless, Douglas grew up believing that the family was destitute and dependent on the money he, his sister, and brother earned from odd jobs.

Julia Douglas was both over-protective and extremely ambitious for her oldest son, who was known as Orville throughout his childhood. She pushed him to achieve intellectually and academically, and frequently recited a speech she had composed "nominating" him for the presidency. Despite, or perhaps because of, his mother's over-protectiveness, young Orville sought to overcome his small size and skinny legs, for which he was teased, by competing in neighborhood sports. At the suggestion of a friend, he began hiking to strengthen his legs, repeatedly walking several miles from his home to climb a 500-foot hill near Selah Gap. The exercise, and a growth spurt, eventually allowed Orville to play center on his high school basketball team.

More importantly, wilderness hiking became and remained a central part of his life. Orville and his high school friends often traveled to the Cascade Mountains that rose dramatically a short distance west of Yakima to hike the forests and meadows and to fish in the mountain lakes and streams. Orville and his brother Art spent weeks on long marches over the rugged trails. For Douglas, the peace and beauty of the mountains provided an escape from the problems of daily life and inspired a permanent love of wilderness in general and the South Cascades in particular.

As valedictorian of his high school, Orville was offered a full tuition scholarship to Whitman College in Walla Walla, where his sister Martha was starting her second year. Since their mother insisted that he had not only to support himself but also to send money home, in addition to his studies Douglas worked as a janitor in the morning, at Falkenberg’s Jewelers in the afternoon, and waiting tables at a boarding house for lunch and dinner. Despite this schedule, he found time to join a fraternity and participate in the debate team, student plays, and other activities. When the United States entered World War I while he was in college, Douglas joined the Students' Army Training Corps.

Columbia and Yale

After graduating from Whitman in 1920, Douglas returned to his hometown (which in 1918 had changed its name from North Yakima to Yakima) and took a job at the high school teaching English and coaching the debate team. Unhappy in the position, Douglas also took a part-time job as a reporter and copyeditor on the local newspaper and occupied himself by writing cowboy stories and novels under a pen name. By 1922, he decided to pursue a career in law and was accepted by Columbia University Law School in New York.

Before heading east, Douglas proposed to Mildred Riddle, the Latin teacher at Yakima High School, whom he had been dating since 1921. The couple married in 1923, but Mildred continued to teach in Yakima until 1924, sending money to help her husband through law school. Douglas was not second in the Columbia Law School class of 1925 as he would later claim, but he did well enough to win both a job at the prestigious Wall Street law firm of Cravath, Henderson & deGersdorff and an offer to teach two courses at Columbia as a lecturer.

But despite this promising beginning, Douglas was not happy. The pressure of grueling 80 to 90 hour work weeks led him to quit Cravath after four months, only to return several months later. And he missed the West so much that he spent an abortive few months (or days, depending on the source) trying to establish a law practice in Yakima before deciding he could not give up the security of his jobs in New York.

By then his natural talent as a legal researcher and teacher led to the offer of a full time teaching position at Columbia for the 1927-1928 school year, and Douglas settled down as a law professor. Douglas's image as one of the leading young legal scholars in the country was enhanced the next year when he was hired away from Columbia by Robert Maynard Hutchins, the new activist dean of Yale Law School. At Yale, Douglas continued to make a name for himself in the fields of corporate and bankruptcy law, which became a particularly hot area after the Depression began in 1929.

Bill and Mildred Douglas both enjoyed faculty life in New Haven. Their two children were born there, Millie in 1929 and Bill in 1932. The family frequently returned to the Northwest to hike and ride horseback in the Cascades and in the Wallowa Mountains of northeast Oregon, where they eventually built a vacation cabin.

SEC Commissioner

With the inauguration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1881-1945) in 1933, Douglas, like many other politically ambitious lawyers and professors, looked to join Roosevelt's New Deal administration. Douglas hoped for a position on the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which was created by the 1934 Securities Exchange Act to regulate Wall Street, but the commission seats went to others. However, the SEC commissioners chose Professor Douglas to lead a study of protective committees, which were supposed to protect investors during corporate bankruptcies and receiverships, but in practice often looked out for the interests of company officers rather than investors.

Douglas gained publicity at hearings where he grilled corporate lawyers and trustees, including one of his old bosses from the Cravath firm. In 1936, he was appointed a commissioner. When the original SEC chairman Joseph P. Kennedy (1888-1969) stepped down and was replaced by Commissioner James Landis, Roosevelt appointed Douglas to Landis's former seat in 1936. On the SEC, Douglas was known for his hard-hitting speeches attacking financial speculators and calling for greater government regulation of stock markets.

He became a leading candidate for chairman when Landis resigned in 1937. With lobbying help from New Deal allies including legendary political operative Thomas "Tommy the Cork" Corcoran, Douglas gained the chairmanship on September 21, 1937. The centerpiece of Douglas's tenure as chairman of the SEC was his successful battle to force greater regulation on the New York Stock Exchange. Douglas's efforts were aided when it was revealed that Richard Whitney, a past Exchange president and leading opponent of regulation, had been stealing from client accounts and that his colleagues had not prevented the thefts. In the wake of the Whitney scandal, the Exchange agreed to the reforms the SEC demanded, and Douglas became a hero of the New Deal.

Supreme Court Appointment

Douglas's prominence on the SEC helped paved the way for his appointment to the Supreme Court in 1939, although he was also aided by the skillful lobbying of Tommy Corcoran and other administration allies such as Interior Secretary Harold Ickes (1874-1952), and by the fact he had grown up in Yakima. When Justice Louis Brandeis (1856-1941) retired early in 1939, Western Senators made it clear that they wanted Roosevelt to appoint a replacement from their region, which was currently unrepresented on the Court.

The leading contender was Washington Senator Lewis B. Schwellenbach (1894-1948). Douglas's allies took advantage of Schwellenbach's feuds with fellow Washington Senator Homer T. Bone (1883-1970) and the fact that Attorney General Frank Murphy disliked him to eliminate the senator from contention. All that remained was to establish Douglas, until then publicly identified as a law professor from Connecticut, as a true Westerner. An intensive lobbying campaign paid off when the Washington State Legislature supported Douglas along with Schwellenbach for the court seat, and influential Idaho Republican Senator William Borah praised Douglas as a "native son" of the West.

President Roosevelt announced Douglas's nomination on March 20, 1939, and the Senate confirmed the appointment less than three weeks later. On April 17, 1939, at the age of 40, William Douglas was sworn into the Supreme Court seat that he would hold for 36 years. Douglas joined Roosevelt appointees Hugo Black, Stanley Reed, and Felix Frankfurter and was soon followed by Frank Murphy and Robert Jackson, transforming the Court from the conservative majority that had blocked early New Deal legislation.

Although the Roosevelt appointees voted together at first, often following Frankfurter’s lead, a fundamental split developed between Frankfurter, whose emphasis on judicial restraint often led him to reject constitutional challenges to restrictions on speech or religious activity, and Black, the one-time Ku Klux Klan member who became one of the most uncompromising defenders of the Bill of Rights ever to sit on the Court. Douglas allied himself with Black, his closest friend on the Court. The division was personal as well as philosophical, as deep animosity developed between Black, Douglas, and Murphy on one side and Frankfurter and Jackson on the other.

Not every case followed these line-ups, however. When, in a decision that has since been generally condemned, the Court upheld Roosevelt’s executive order confining Japanese American citizens in internment camps during World War II, Black joined Frankfurter in the majority and Douglas followed his ally, leaving Jackson, Murphy, and Owen Roberts to dissent. Douglas subsequently acknowledged that his vote supporting Japanese internment was wrong.

Presidential Ambitions

When he joined the Court, neither Douglas nor anyone else expected that he would remain there the rest of his working life. Relatively young, very ambitious, and frequently feeling confined in the role of judge, Douglas envisioned rising higher -- to the presidency. A favorite of the liberal wing of the Democratic party, he was touted as a potential successor to Roosevelt in 1940, until the president decided to seek an unprecedented third term, and was considered briefly as a vice presidential prospect that year. Douglas nearly realized his White House dreams four years later, when an ailing President Roosevelt made it known privately that Douglas was his first choice for the vice presidency. However Democratic Party bosses, led by party chairman Robert Hannegan of Missouri, preferred Harry Truman (1884-1972).

Despite a concerted behind the scenes effort led by Corcoran on behalf of Douglas (who publicly declared he had no political ambitions), the 1944 Democratic Convention chose Truman, and the Missourian became president when Roosevelt died the next year. Douglas was offered the vice presidential nomination in 1948 by Truman, his 1944 rival, who wanted to bolster his declining standing with liberal Democrats. But this time Douglas chose not to give up the security of the Supreme Court to run on a ticket that at the time appeared doomed.

By the 1950s, with little realistic hope left for the White House, but not fulfilled as a judge, Douglas began to turn his prodigious talent and energy in other directions. In 1950 he published Of Men and Mountains, a memoir and nature book that became a critical and popular success. The vivid (albeit somewhat embellished and exaggerated) account of his early life and mountain adventures contributed to the Douglas legend. The book’s success led to many more, as Douglas eventually published over thirty titles. He soon realized that he could fund the foreign travel he loved by publishing books about the lands and peoples he visited. He also wrote books explaining his legal views and two more volumes of autobiography, Go East Young Man and The Court Years.

Promoting Conservation

Many of Douglas’s books and other writings centered on nature and promoting conservation. With his long-standing love of the wilderness and his high-profile public position, Douglas became one of the early leading voices of the growing environmental movement. Perhaps his most celebrated environmental achievement came in 1954, when he opposed a plan to build a parkway along the historic Chesapeake and Ohio canal and towpath between Washington, D.C. and Columbia, Maryland. After the Washington Post endorsed the proposed highway, Douglas publicly challenged the newspaper’s editors to walk the canal path with him, to see the natural areas that the road would destroy. More than 50 people joined the hike, and the ensuing publicity swung public opinion (the Post reversed its position) in favor of saving the canal, which officially became a national historical park in 1971.

Douglas enjoyed and wrote about wilderness excursions around the country and the world, but he had a special affection for the south central Cascades that he had traveled since boyhood. In 1948, Douglas stayed for the first time at the Double K, a tourist ranch in tiny Goose Prairie in the Bumping River valley, 57 miles from the city of Yakima and 17 miles from the nearest telephone. For the rest of his life, Douglas returned to the ranch for pack trips into the mountains, and later built his own summer home in Goose Prairie. The Supreme Court's annual recess between June and October allowed Douglas to spend long summers at his Goose Prairie retreat, a privilege that the justice zealously guarded.

Through the 1950s Douglas remained often in the minority on the Court. With staunch liberal allies such as Frank Murphy and Wiley Rutledge succeeded by more conservative Truman appointees, Douglas and Black were often the only dissenters as the Court, like the rest of the country, became caught up in the anti-communist hysteria of the day. Sometimes accused of communist sympathies because of his opinions, Douglas actually despised communist governments for their repression of individual rights, but believed equally fervently that imposing loyalty oaths or punishing people for teaching political beliefs was emulating rather than opposing repression.

Protecting Privacy

The liberal Earl Warren (1891-1974) became chief justice in 1953 and helped engineer a unanimous opinion in the historic 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision abolishing school segregation, but it was not until the early 1960s that the Warren court had a solid liberal majority and Douglas was able to make his views law. His most notable contribution came in the landmark Griswold v. Connecticut decision (striking down state restrictions on the sale of contraceptives to married couples), in which the Court recognized a constitutional right to privacy. Douglas had long argued that the Constitution protects individual privacy, although the word is not found anywhere in the Bill of Rights. The Griswold decision adopting his view became the foundation for many later decisions, including the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that limited government ability to prohibit abortion.

However, despite his long tenure and strongly held views, it was not Douglas but Warren and William Brennan (1906-1997) who emerged as the leaders of the liberal bloc. Douglas appeared to make little effort to influence other judges, and legal scholars have criticized his rulings, even the landmark Griswold decision, for being superficial and lacking the necessary analysis to support the results reached. Even many who admire his positions believe he did not live up to his potential on the Court.

Off the Court, Douglas’s behavior generated even greater criticism. In the early 1950s, he scandalized some when he divorced Mildred and married Mercedes Davidson, 18 years younger than him, who left her husband for the justice. It was the first divorce in the Supreme Court’s history. Douglas then proceeded to get the Court’s second and third divorces as well, each time immediately remarrying a woman more than 40 years younger than he was. He divorced Mercedes in 1963 and married 23-year-old Joan Martin five days later. In 1965, he met Cathy Heffernan, then a 22-year-old college student and waitress in Portland, Oregon. They married the next year, three weeks after Douglas’s divorce from Joan was final, and remained married until his death.

The Nixon Years

Douglas was also criticized for some financial dealings, in particular his involvement with a foundation financed by Albert Parvin, a businessman who had investments in Las Vegas casinos and alleged ties to underworld gamblers. Citing Douglas's financial entanglements, marital record, and stinging attack on the "establishment" in his 1970 book Points of Rebellion, conservative Republican Congressmen led by future President Gerald Ford (1913-2006) made several attempt to impeach the justice. Ford's efforts, which failed, were widely viewed as retaliation for the Senate's rejection of two of President Richard Nixon's Supreme Court nominees.

Before and after the impeachment attempts, Douglas was an outspoken critic of Nixon's policies. He denounced what he saw as Nixon's attacks on the Bill of Rights, dissenting when a Court majority that included three Nixon appointees upheld U.S. Army surveillance of civil rights and anti-war activists, and voting with the majority to allow The New York Times and Washington Post to publish the classified history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam known as the Pentagon Papers.

Douglas also repeatedly tried, without success, to get his colleagues to review the legality of U.S. military operations in Vietnam. His most dramatic effort came in August 1973, after New York Representative Elizabeth Holtzman and others sued to stop Nixon's bombing of Cambodia. Seeking a stay of the bombing until the full Court could rule, ACLU attorneys tracked Douglas down at his Goose Prairie home, and he agreed to hold a hearing at the federal courthouse in Yakima. Douglas granted the stay on August 4, ordering an immediate halt to the bombing, but the eight other members of the Court convened by telephone and reversed Douglas six hours later. (The Cambodia bombing ended on August 15, 1973, as Congress, with Nixon's reluctant agreement, had previously ordered.)

Despite declining to intervene in the war, the Court soon made clear that Richard Nixon was not above the law. In a 1974 decision that Douglas considered one of the most important in which he participated, the Court ruled unanimously that Nixon could not use executive privilege as an excuse not to release the Watergate tapes. Shortly after the decision, Nixon resigned the presidency.

Legacy of Liberty and Wilderness

Even after a heart attack in 1968, Douglas continued an active life of work, travel, and wilderness excursions. Then on the last day of 1974, while on vacation in the Bahamas, he suffered a massive stroke that left him permanently impaired. Confined to a wheel chair, his mental energy drained, Douglas struggled to continue his work on the Court, but could not do so. He resigned on November 12, 1975, having served longer than any other justice has. Douglas died on January 19, 1980, and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Following his death, the federal court building in Yakima was named in his honor. The William O. Douglas Wilderness in the Cascade Mountains near his beloved Goose Prairie also commemorates Douglas and the wild areas he championed.

Earlier, at a 1977 ceremony that Douglas attended, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park that exists because of his efforts was officially dedicated to Douglas. Douglas's legacy endures in these and other natural areas that he helped preserve, and in the rights of privacy and other individual liberties that he helped protect in his many years on the nation's highest court.