From 1898 to 1971, lightships were important elements in the system of navigation aids along Washington's coast. On May 22, 1898, Light Vessel No. 67 became the first on Washington's coast. She arrived at Umatilla Reef, 11 miles south of Cape Flattery. In 1909, Light Vessel No. 93 became Washington's second lightship by taking station on Swiftsure Bank, 14 miles northwest of Cape Flattery. Thus, Washington had two of the Pacific Coast's five lightships. Today lightships survive only as museum exhibits.

From Cape Mendecino to Cape Flattery

Maritime traffic bound for or departing Washington's Columbia River ports also made use of Oregon's only lightship, which was stationed off the Columbia River Bar. This made the Columbia Bar in one sense a "Washington" station because Columbia Bar lightships frequently served as relief vessels at Umatilla Reef and Swiftsure Bank.

The United States Lighthouse Service, which operated the lightships, placed the remaining two Pacific Coast light vessels at the San Francisco Bar and at Blunt's Reef north of San Francisco. The lightships in California, Oregon, and Washington complemented the service's lighthouses on the Pacific Coast. In Washington, these were at Cape Disappointment, North Head, Willapa Bay, Grays Harbor, Destruction Island, and Cape Flattery. They completed a chain of coastal beacons that stretched from California's Cape Mendocino to Washington's Cape Flattery. The arcs of the principal lights overlapped except for three short intervals.

Origin and Purpose of Lightships

The first world's lightship went into operation in 1732 at the Nore, a sandbank in the estuary of England's Thames River. Thereafter, in locations needing navigation aids but where lighthouse construction proved impossible or exorbitantly expensive, authorities, often reluctantly, substituted lightships. Officials responsible for navigation aids soon learned to prefer lighthouses to the floating beacons. Lightships, they learned, cost more to operate and maintain, and storms could drive them off station.

Lightship locations were usually approaches to ports or bays, or the outer limits of off-lying dangers such as reefs. In addition to their adaptability to localities inappropriate for lighthouses, lightships had the advantage of providing light and fog signals for which vessels could steer directly without fear of running aground. Early United States Coast Pilots even encouraged ships to run close aboard lightships. But following this advice had its hazards. In United States waters, ships have rammed lightships more than 100 times. In five instances, the lightships sank.

The first lightship in American waters began operation on Chesapeake Bay in 1820. Between 1820 and 1983, when the Coast Guard decommissioned the last American lightship, 179 of the vessels entered American service. At the peak of the lightship era in 1909, 56 lightships were in United States service.

Characteristics and Capabilities

American experience with lightships by the end of the nineteenth century led to a uniform design. Standard features included a length of about 135 feet, flat bottoms, rounded bows, bilge keels intended to reduce rolling, mushroom anchors weighing up to 7,800 pounds, and decks designed to allow water runoff. Lantern galleries with primary and standby lights on double masts permitted the ships' beacons to be constantly illuminated. Radios became standard equipment for offshore lightships after 1901.

Electric beacons first appeared on lightships in 1892. Prior to that, oil-burning lamps hung from the ships' double masts. The lamps' "galleries" encircled the masts so that no obstruction blocked the lanterns, no matter from what point sighted. In daylight hours, keepers could lower lamp galleries into open-topped rooms at the base of their masts for servicing.

In 1912 the Light House Service assigned to its lightships visual call signs based on the International Code of Signals. These call signals, displayed through signal flags, added to the ways in which mariners could identify particular lightships. Until the 1920s, daymarks or distinctive round hoops mounted to one or both mastheads further identified each lightship.

Radios permitted not only ship-to-shore and ship-to-ship communication. They also enabled lightships to ask immediately for help for themselves or other craft, transmit critical weather bulletins, and report if blown off station. The U.S. Navy first assigned two-letter radio call signs for lightships. Three- and four-letter call signs developed by the U.S. Bureau of Standards soon replaced them. After 1921, lightships began to broadcast radio beacons that mariners could use to plot their location relative to the lightship.

When the Coast Guard took over the duties of the Light House Service in 1939-1940, it assigned new visual and radio call signs to lightships. The same radio call and flag hoist identified each lightship station with a separate call sign and hoist used by light vessels when they were off station. No. 113's radio and visual call sign from 1940 to 1968 at Swiftsure Bank was, for example, NMJA.

Submarine bells went into regular use in 1906. Suspended beneath some light vessel to a depth of 25 to 35 feet and operated by compressed air, the bells exhibited distinctive tones audible to distances of 10 miles or more to ships equipped with appropriate listening devices.

A yard on the typical light vessel's foremast allowed hoist of three or four International Code Flags. Sound signals could be provided by compressed air and steam-operated horns located either atop deckhouses or on masts and steam whistles on funnels. Some ships also had 1,000-pound bells on their foredecks.

In 1891, the U.S. Light House Service introduced its first self-propelled lightships. Prior to 1923, steam engines were universal. After 1923, diesel and diesel-electric power gradually replaced steam plants.

The Typical Lightship

A typical lightship crew consisted of master, mate, chief engineer, assistant engineer, lamp trimmer, radio operator, cook, two deckhands, and three firemen.

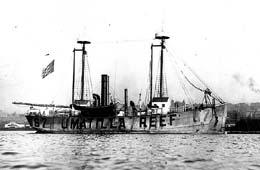

Lightships usually had straw-colored or red hulls. Either side of the hull bore the station's name painted in large letters. After 1940, the U.S. Coast Guard standardized its lightships' paint schemes. Red hulls featured six-and-one-half-foot white letters announcing the light station's name. White paint distinguished deckhouses and boats, and mast and trim were buff. The ships became known by the names of their stations. Thus, Light Vessel No. 67 at Umatilla Reef from 1898 was known as the Umatilla Reef. When No. 93 replaced No. 67 in 1930, No. 93 then became the Umatilla Reef.

Life on Board

Lightship duty was arduous. One lightship sailor said, "When it is in any way rough, she [his lightship] rolls and labors to such a degree as to heave glass out of lanterns, the beds out of berths ... rendering her unsafe and uncomfortable" (Flint). Another described duty off the Washington coast:

"Most of the guys were puking their guts out into a bucket — the ones not affected were starving because the galley is shut down .... Sleep was often impossible due to the violent motion, the roar of gale force winds, and the bellow of the fog signal every thirty seconds or so" (Gill).

Blasting at 140 decibels, foghorns sent shock waves and vibrations throughout the ships on which they were mounted.

The typical lightship's constant pitching, rolling, and yawing gave sailors few moments of relaxation. As their bodies responded to their ship's continual movement, neck, shoulder, and leg muscles flexed constantly. Walking about the ship required one or two handholds at all times. For those interested in eating, plates and cups often wouldn't stay on tables despite fiddles.

From the Swiftsure Light Station, one skipper reported in December 1932 the mayhem wrought by a wave rushing into the pilothouse:

"Seaman Harrais was knocked unconscious [by being thrown against the steering wheel], suffered a broken arm, and had many cuts on top of his head, forehead, and arms. He also suffered from a badly wrenched back. Water had been breathed into his lungs from lying in about a foot of water"(Noble).

A radio operator on the Umatilla Reef Station in the 1930s recalled waves breaking over the upper deck and squirting water through the radio shack keyholes.

In the best of circumstances, Light House Service crews served four-month tours of duty before relief, but the Coast Guard later reduced this to 30-day stints. Lightship duty, recalled one skipper, was a "harsh, cruel way of life," shunned by sailors "almost as a prison sentence" (Gill).

Columbia Bar Station

Light Vessel No. 50, built at San Francisco, was the first lightship on the Pacific Coast. Her 112-foot hull had a steel frame with wood planking. She had no propelling power except sails. The tug Fearless towed her from California to the mouth of the Columbia River in 1892. No. 50, anchored a few miles west of the whistle buoy marking the Columbia River Bar and remained there until 1894. Then she moved three miles southeast to be nearer vessels entering the river.

On November 28, 1899, gale force winds broke the heavy chains linking No. 50 to her anchors and drove the helpless ship onto Cape Disappointment on the Washington side of the Columbia River entrance. Six months' effort at hauling her off the beach came to naught. In June 1900, three contractors suggested moving No. 50 overland to Baker's Bay. This cove on the north shore of the Columbia, just inside the river entrance, lay about 700 yards from the grounding site.

Two Portland house movers, Andrew Allen and H. H. Roberts, agreed to recover No. 50 in 35 working days for $17,500. Allen and Roberts planned to build a cradle to which jackscrews could lift the lightship. Then they would move the 112-foot craft forward on rollers through the woods between Cape Disappointment and Baker's Bay. Work began on February 22, 1901. At 11:45 p.m. on June 2, 1901, the movers launched No. 50 into deep water at Baker's Bay, then arranged for her tow to Astoria where she would be repaired.

After laying No. 50 up at Astoria in 1909, the Light House Service had her surveyed and condemned in 1915. The service then sold her at public auction for $1,667.99 on April 27, 1915. Subsequent owners used her as a freighter in Alaskan waters under the name of San Cosmo & Margaret until 1935.

Umatilla Reef Station

Umatilla Reef Lightship Station was located offshore from the small Indian village of Ozette, 11 miles south of Cape Flattery. About four miles seaward from Cape Alava, and 2.5 miles south of Umatilla Reef, the station aided mariners transiting the coast or making landfall after transoceanic voyages.

The 112-foot, 450-ton Light Vessel No. 67 first took station at Umatilla Reef in 1897, beginning a vigil by No. 67 and her successors that lasted until 1971. The station took its name from the several small black rocks named for the liner Umatilla, whose bottom they ripped out in February 1884. Considered a rugged post, the Umatilla Reef station was exposed to seas and winds from every direction. During the life of the station from 1897 to 1971, high winds blew adrift or dragged various lightships off station six times.

The steam-powered No. 67 had been stationed off the Columbia River bar before being moved to Umatilla Reef in 1897. Built at Portland at a cost of $77,000, she had a 122-foot, seven-inch composite (steel sheathed with wood) hull and two steel masts. She remained at Umatilla Reef until 1905. Then she returned to the Columbia River in 1905-1906 before anchoring again at Umatilla Reef until 1930, when she was sold out of service. The Lighthouse Service converted her illuminating apparatus from oil to electricity in 1900, equipped her with a submarine bell in 1910, and installed a radio in 1921. Her other equipment included a steam chime whistle and a hand-operated bell. Pacific Northwest author Archie Binns, who was once a lightship sailor, used No. 67 as the setting for his book Lightship. A series of successors followed No. 67 until in 1971, the Coast Guard decided to use a lighted whistle buoy rather than lightships at Umatilla Reef.

Swiftsure Bank Station

Swiftsure Light Station took its name from Swiftsure Bank, an undersea formation rising from the continental shelf off the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca about 14 miles northwest of Cape Flattery and extending for about three-and-one-half miles. The Swiftsure station served not only vessels entering the Strait, but also hundreds of fishing vessels that operated in the area from June to November each year.

Light Vessel No. 93 (later redesignated WAL 517) was the first lightship to take up station at Swiftsure Bank. Built at Quincy, Massachusetts, in 1908, the 135-footer arrived at Swiftsure in 1909 and remained until 1930. Steam-powered and screw-driven, she had a steel hull, two steel masts, and a single smokestack amidships. Her illuminating apparatus was a cluster of three oil lanterns raised to each masthead. Other equipment included a steam chime whistle and a hand-operated bell. In 1909 she received a submarine bell; in 1921, a radio; in 1924, a radio beacon; and in 1930 electric lanterns to replace her oil lamps.

Until the Coast Guard took over in 1939, a yellow hull with black lettering distinguished the Swiftsure Bank lightship from the vessel at Umatilla Reef, just 22 miles to the south.

From 1930 to 1939, No. 93 served at Umatilla Reef and from 1939 to 1951 at the Columbia River Bar. The Coast Guard decommissioned No. 93 in 1951 and sold her on November 2, 1956. For most the years between 1930 through 1951, Light Vessel No. 92 was at Swiftsure. From 1951 until 1961, when the Swiftsure station was disestablished, Light Vessel No. 113 (later WAL 535) was on duty.

In 1976, the 46-year-old No. 113 (WLV 535), was on her way to Portland to be scrapped. The 134-foot vessel, built at Portland in 1930, had been at Gig Harbor, where locals had hoped to use her as the basis for a maritime museum.

Musical Chairs with Lightships

In 1908, the Pacific coast lightship fleet expanded when the tenders Sequoia, Manzanita, and Kukui, and Lightship No. 88, No. 92, and No. 93 completed a 124-day voyage from New to San Francisco through the Straits of Magellan. These additions began a game of musical chairs with lightships.

Light Vessel No. 88 (later WAL 513) had been at the Columbia River from 1909 until 1939, but from 1939 until 1942 and again from 1945 to 1959 was at Umatilla Reef. When the United States entered World War II, all the Pacific Coast lightships moved off their stations and did not return until 1945. When they did, the Coast Guard added radar to their navigation equipment.

After using No. 88 briefly (1959-1960) as its West Coast relief vessel, the Coast Guard sold her for scrap on July 25, 1962. From 1963 to 1975, No. 88 became a floating exhibit at Astoria, Oregon's Columbia River Maritime Museum. In 1975, the Maritime Museum sold her to an entrepreneur who used her as the centerpiece of a failure-destined floating restaurant scheme at Newport, Oregon.

In 1961, WLV 190, which had seen prior service off the Massachusetts coast, took station at Umatilla Reef. She remained there until 1971, when she was retired and decommissioned. The Coast Guard turned WLV 190 over to Youth Adventure, Inc. at Seattle.

When WLV 190 transmitted "Off station, all navigation aids secured," in 1971, this left only two lightships on the West Coast. These were WLV 604 at the mouth of the Columbia River until retired from lightship duty in 1979 and replaced by a Large Navigation Buoy and WLV 605, which served as West Coast relief vessel from 1969. She was sold out of government service in 1976. 604 replaced No.88 as a floating exhibit at the Columbia River Maritime Museum. 605's first private owner, Alan Hosking of Woodside, California, donated the ship to the United States Lighthouse Society on December 31, 1986. She subsequently became a floating exhibit at Oakland, California.

In Washington, No. 83 (later WLV 508) found a final resting place as a museum ship at Seattle's Northwest Seaport. She had spent time at all five Pacific Coast light stations between 1905 and 1960, when she concluded her career as a relief ship for the Thirteenth Coast Guard District in Seattle.

The End of the Lightship Era

The end of the lightship era in America began when a 1957 study estimated the annual cost of a lightship station at $1.32 million and determined that each station required 1.32 vessels. Seeking to cut costs, the U.S. Coast Guard began to replace the lightships with either offshore light structures similar to oil platforms or the new Large Navigation Buoys (LNBs).

The steel 60-ton LNBs with 35-foot tower masts topped with 35-foot radio beacon antenna replaced deepwater lightship stations. Radio circuits provided remote control of navigation aids on the buoys. These included lights, sound signals, and radio beacons.