As a young girl in Maine, Mary Richardson set her mind to become a missionary. Upon marrying Elkanah Walker in 1837, the couple set out for the Oregon Country. They settled among the Spokane Indians to teach and preach at their mission, Tshimakain, located 25 miles northwest of present day Spokane. Mary’s intimate 125,000-word diary tells of crossing the continent with fur traders, building a rustic shelter in the wilderness, ministering to the Indians, and raising a family under trying conditions. Her words reveal her frustrations, spirit, honesty, and perseverance. She is a symbol of the strength of all pioneer women. Following the murder of the Dr. Marcus Whitman party, near Walla Walla, Mary and her family moved themselves to the peaceful Willamette Valley where they spent the rest of their lives. The work of missionaries paved the way for the next wave of pioneers to cross the Rockies to Oregon.

Choosing the Life of a Missionary

Mary Richardson was born in Maine in 1811. Around this time America was swept up in the Great Awakening that prompted the faithful to strike out around the world in missionary zeal. Mary, the second of 11 children, attended Maine Wesleyan in the early 1830s. Her course of study included history, natural philosophy, chemistry, natural history, botany, mental philosophy, mathematics, French, and Spanish. Mary taught school in Maine, yet she had always been interested in missions. The life of a missionary was the most exciting career open to women at this period. "At the age of 9 or 10 my mind first became interested in the cause of missions, and I determined if it ever were in my power I would become a missionary. This determination I never forgot" (Mary Richardson Walker Diary, December 5,1836).

Mary hoped to be sent to Africa but the Zulu wars were breaking out and the American Board of Missions was reluctant to send a single woman missionary anywhere, let alone to a war zone. The Board also knew of a single male desiring a missionary assignment. The Board wanted to send out missionaries as husband and wife teams, so they played cupid and sent Elkanah Walker of Bangor to meet Mary Richardson. Mary recorded her initial impression, "I saw nothing particularly interesting or disagreeable in the man. He is a tall and rather awkward gentleman" (Diary, April 22, 1837). Elkanah proposed marriage within 48 hours of their meeting and she accepted.

In 1836, William H. Gray had gone west with Dr. Marcus Whitman, his wife Narcissa, Reverend Henry Spalding, and his wife Eliza. The Whitmans worked among the Cayuse and the Spauldings with the Nez Perce at Lapwai. In 1837 Gray returned east to get married and ask for more missionaries for the remote Pacific Northwest. The American Board of Missions responded. In the words of Rev. W. J. Armstrong, "A white population may be expected to gather pretty rapidly on the Columbia River and in a few years, if the Gospel is not now given to the poor Indians, the vices and diseases of the whites may spread among them and sweep them away." The Board sent the Walkers along with three other couples, all newlyweds, to the land beyond the Rockies to spread the Gospel and save the Indians.

The Journey West

The extraordinary honeymoon journey began early in 1838. The Walker newlyweds left Maine for Boston with a horse and buggy. This was followed by a coastal steamer trip to New York. First a stagecoach, then a train, at 10 mph, brought them to Pittsburgh. Here they picked up the steamboat Norfolk to St. Louis. It seems all means of transport available in the 1830s were part of the adventure that was only beginning.

At Independence, Missouri they met up with their companions for the overland trip to Oregon, nearly 2,000 miles across the wilds. In addition to Mary and Elkanah Walker, the party now included three other newly married missionary couples: Cushing Eells and his wife Myra, Asa Smith and his wife Sarah, W. H. Gray and his wife, plus three single men. Each couple was limited to 140 pounds of provisions, including a tent. Each person was permitted to pack a two-foot-long valise with their personal effects. On March 13, the missionaries received a passport to Oregon from the U.S. War Department "to pass through the Indian country to the Columbia River" (Drury, 68). Mary rode horseback the entire way on her tiny sidesaddle, feeling the effects of pregnancy all along the way.

Descriptions of the West in the 1830s were based upon rumors, exaggerations, and speculation with very few facts to get in the way. Washington Irving’s narrative Astoria states, "While passing through the great defile you are supposed to be at 10,000 feet while you look up to either hand to snow capped peaks rising 8,000 to 10,000 feet above you ... surpassing all other mountains on the globe except the highest peaks of the Himalaya." Deserts, impassable mountains, unfordable rivers, wild beasts, and unfriendly Indians were part of the commonly held picture. Yet, west the newlyweds headed full of determination and faith.

The missionaries attached themselves to a party of fur traders. These agents of John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company agreed to act as guides through the Rockies. This was a most valuable service in the unmapped and almost unknown frontier.

It would be hard to find a less congenial group of people than this group of missionaries. Every one of the newly married missionaries was brimming with good intentions, but they bickered about anything and everything. Two couples shared a 9- x 12-foot tent. It seems each could find something that bothered them about the others. Mary noted "There is scarcely one who is not intolerable on some account" (Diary, April 23, 1838). They were all strong-minded determined people.

Mary found out very soon that her husband was subject to moods of melancholy and bad temper. She wrote in her journal on April 11 that she wished he wouldn't embarrass her by his continual watchfulness. She felt he was critical of everything she did. She wrote, "Should feel much better if Mr. W. would only treat me with some cordiality. It is so hard to please him I almost despair of every being able to" (Diary, April 24, 1838). The next day these words: "Rode twenty-one miles without alighting. Had a long bawl. Husband spoke so cross I could scarcely bear it" (Diary, April 25, 1838).

Another diary entry seemed to carry an ominous warning: "Sleep disturbed by prowling wolves. Some horses gone. May have been Indians" (Diary, April 26, 1838). Yet there were to be no hostile attacks by the Indians during the journey.

Another night, "We were scarcely expecting rain and made no preparation. In the night it stormed tremendously. Our bed was utterly flooded. Almost everything wet. No wood, so used ‘prairie coal’. I am thinking how comfortable my father’s hogs are" (Diary, May 17, 1838).

Mary had an appreciation for the spectacular land through which she was traveling. "The bluffs resemble statuary, castles, forts, as if Nature, tired of waiting the advance of civilization, had erected her own temples" (Diary, May 26, 1838).

On June 6th Mary was in ill health. In keeping with the medical practices of the day, she was bled. "Find it difficult to keep up a cheerful flow of spirits. Think the bleeding did me good though it reduced my strength more than I expected" (Diary, June 5, 1838). Later on she had a tooth pulled. All this time she was pregnant with her first child.

Soon they camped at Independence Rock where Mary climbed to the top and, as a geologist would have done, chipped away a piece of the rock to add to her collection of plant and mineral specimens. Her curiosity seemed unlimited.

At Wind River, in Wyoming, they met the American Fur Company Rendezvous of 1838. Here they met Jim Bridger, Joe Walker, Robert Newell and Joe Meek. Mary baked bread for the occasion. Joe Meek said it was the first bread he had eaten in nine years. Provisions were expensive; tobacco was $6 a pound and Elkanah Walker paid $80 in goods for a pony that Mary felt was worth no more than $20 back in the United States. She reported to her diary that "My horse fell and tumbled me over his head. Did not hurt me" (Diary, June 24, 1838). But she did not say if this was the new pony Elkanah purchased at the Rendezvous.

On August 29, 1838, after six months on the trail, the party arrived at Dr. Marcus Whitman’s mission, Waiilatpu, near Fort Walla Walla. A book about Mary Richardson Walker written in 1945 by Ruth Karr McKee was subtitled The Third White Woman To Cross The Rockies.

Conditions were crowded at the small mission and there were tensions among all parties. The Cayuse Indians were very curious, constantly peering through the windows. Mary wrote "I will teach them better manners as soon as I can acquire language enough" (Diary, August 29, 1838). Mary gave birth to her first child while at Waiilatpu, a son she named Cyrus. He was the first boy born to an American couple in the Oregon Territory.

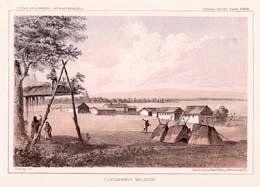

Life at Tshimakain

Elkanah Walker and Cushing Eells scouted north of Waiilatpu and found a place for their own mission among the Spokane Indians. The site, which they called Tshimakain, was located 25 miles northwest of present-day Spokane. The present-day community of Ford, Washington, is near the site of their mission.

In a letter to the American Board, dated October 15, 1838, Elkanah spoke of the nature of the task ahead in working with the Indians. "They must be settled before they can be much enlightened. While they retain the habit of roving they are but a part of the year under religious instruction of any kind. Their children cannot be gathered into schools and instructed. It is necessary that they should be settled and made cultivators of the soil as speedily as possible to save them from extinction" (Drury, 116). Easier said than done.

The Walkers lived nine years in this remote outpost. Mary raised six children during these years in a 14-square-foot log cabin with walls chinked with mud. The dirt floor was strewn with pine needles. The roof of poles, grass, and dirt leaked mud during rainstorms. Cloth served as windows until glass arrived many months later. One day the wall fell in: "This morning part of the wall of our house fell. Husband was in the room in bed when it began to fall. He escaped without being hurt much. Son’s little chair was broken to pieces. The chimney fell with the wall and just as it fell, it began to rain" (Diary, March 4, 1840). A year later, Mary seemed resigned to her situation. "Cleaning and setting in order our little hut. Hope the day may come when we shall have a better house though I could be contented to live as we now do all my life long" (Diary, March 13, 1841).

On a January night in 1841, the Eells cabin burned down. Mary was outside with the others fighting the fire in temperatures eight degrees below zero. The Eells had to move into the Walker’s cabin. Myra Eells was often ill and Mary cared for both families. One day during this period Mary began washing clothes before breakfast and finished at midnight.

Mary’s workday averaged 16 hours. Her tasks included cooking in a fireplace (she never had a stove), raising a garden, helping with the field work, milking six cows, washing, ironing, cleaning, repairing the cabin, and making soap. The list goes on. "Sat up all night, dipped twenty-four dozen candles" (February 17, 1842). She made all the family’s garments and shoes, and once wrote, "cut out eight pairs of shoes today" (Diary, August 23, 1842). Whenever she could, Mary gave some time to the education of her children. And she reproached herself for not being able to do more for the Indians.

One day she wrote:

"Rose about five. Had early breakfast. Got my house work done about nine. Baked six loaves of bread. Made a kettle of mush and have now suet pudding and beef boiling. I have managed to put my clothes away and set my house in order. At nine o’clock pm was delivered of another son" (Diary, March 16, 1842).

This entry has been often quoted in writings of the West as it symbolizes the hardiness of frontier women.

Mary’s curiosity and latent talents were stimulated by the infrequent travelers who stopped by the mission. Her guestbook included the famous explorer Peter Skene Ogden, members of the Wilkes Expedition, and artist Paul Kane. Later, another artist, John Mix Stanley, visited. Mary resumed her watercolor painting at this time. Examples of her work are with her papers and effects at Washington State University.

As a young woman she was a serious student of science. By 1847, her diary revealed that she had mastered taxidermy. She collected and stuffed birds, snakes, and other animals despite her husband’s lack of enthusiasm or support. She once wryly commented that her husband had decided to give his permission for her to resume her taxidermy. She held her tongue and proceeded to do what she had planned to do anyway.

The Spokane Indians spoke their own language, which was not a written language. The Walkers had difficulty communicating with them, let alone preaching to them or teaching them. Elkanah tried to piece together an alphabet to teach the Indians to read and even attempted to translate the Gospels using the makeshift alphabet. He struggled to translate the first 10 chapters of the book of Mark. In nine years not one Spokane converted to Christianity. The experience was heartbreaking for the Walkers.

Yet the missionaries of the Northwest succeeded in another respect. In 1843 the first great emigration to Oregon took place as a thousand folks headed west. In the words of historian Emerson Hough: "The cowards never started, the weak died along the way. That was how the great Northwest was born." The missionaries had shown the way. They were already in Oregon to greet and aid the newcomers. The resulting increase in the American population assured that, in time, the land south of the 49th parallel would become part of the United States.

On November 29, 1847, a group of Cayuse Indians attacked the Whitman mission and killed 13 occupants, including Marcus and Narcissa Whitman (one man escaped but apparently drowned later). An Indian guide rode to the Tshimakain mission with the news. Those at the trading post at Fort Colville urged the Walkers and the Eells to remove themselves and go to the fort for protection.

Leaving Tshimakain

Upon leaving Tshimakain Mary composed this poem for her children to help them remember their birthplace.

Tshimakain! Oh, how fine, fruits and flowers abounding,

And the breeze, through the trees, life and health conferring.

And the rill, near the hill, with its sparkling water

Lowing herds and prancing steed round it used to gather.

And the Sabbath was so quiet and the log house chapel

Where the Indians used to gather in their robes and blankets.

Now it stands, alas forsaken: no one with the Bible.

Comes to teach the tawny skailu (people) of Kai-ko-len-so-tin (God)

Other spots on earth may be to other hearts as dear;

But not to me; the reason why, it was the place that bore me.

Though the Spokane Indians had always been friendly, the Walkers followed the advice from Fort Colville and left Eastern Washington for the Willamette Valley in Oregon. There Elkanah bought a 100-acre land claim from a man who planned to set out for the California gold fields.

Elkanah took up farming and preached in the Congregational Church at Forest Grove, Oregon. Here Mary had her seventh and eighth children. The Walkers also adopted a child and took in boarders. The Walkers donated some of their land to help in the establishment of Pacific University at Forest Grove.

In 1871 the Walkers returned to Maine for a visit, this time by train. They attended the graduation of their son, Elkanah, from Bangor Theological Seminary. The new graduate then set off to become a missionary in China. Other descendents of the Walker’s were to become missionaries and one became a professor of Biology at the University of Nebraska.

Mary Richardson Walker died in 1897 at the age of 86.

The first entry in her diary was dated January 1, 1833.

"As life is uncertain I write this page that should I be taken away suddenly this book may not be seen except by a sister or some very near and intimate friend and I hope my friend will have the compassion to burn it immediately. Should it by chance fall into the hand of an other pray be so good as to not read it."

Mary intended to pour out her heart and tell the truth as she saw it. The resulting honesty makes the diary a valuable document for historians of the American West. Thankfully it was not burned and is now part of the Walker Papers at the Washington State University Libraries Special Collections.